Writing the life of author and filmmaker Hanif Kureishi: race, class and multiculturalism

Ruvani Ranasinha

“We had been devastated … in ways we didn’t understand by racism”

~ Kureishi, My Ear at His Heart (2004)

In 2023, my biography of the British Asian novelist and screenwriter Hanif Kureishi was published by Manchester University Press.[1] There are three topics I would like to address in this talk.[2] First, why do we need a biography of Hanif Kureishi? What is his significance and achievement? Second, I want to examine the oppositions in Kureishi’s origins and cultural background. And finally, how has Kureishi shaped debates on race, class, and multiculturalism in Britain over the past decades? This seems especially pertinent in view of the worst wave of far right, anti-immigrant violence for almost a century that erupted in Britain on 30 July 2024.

I want to begin with how I came to write this biography. My books on South Asian writing in Britain have been concerned with rethinking British cultural history through re-mapping the place of South Asian minorities within it. South Asian Writers in Twentieth Century Britain: Culture in Translation (Oxford University Press, 2007), Contemporary Diasporic South Asian Women’s Fiction: Gender, Narration and Globalisation (Palgrave, 2016) and South Asians Shaping the Nation, 1870-1950: A Sourcebook (Manchester University Press, 2012) have all explored the ways that South Asian artists and activists have shaped and informed British culture, and indeed, global culture. Recently, I decided to turn to biography to illuminate a larger story of change and the reshaping of post-war Britain. I wanted to reach a broader audience and to engage with lived, intimate experiences of multiculturalism. I decided to tell a story about British multiculturalism through the life of Hanif Kureishi, one of Britain’s most provocative, versatile, and popular writers.

What is Kureishi’s significance and achievement?

I first began to track and understand Kureishi’s importance in influencing public debates on race in Britain while writing my PhD on South Asian writing in Britain at Oxford University. This became my first monograph on Kureishi’s work: Hanif Kureishi: Writers and their Works (2002). Here was someone who had stood up for black and Asian minorities with his outspoken, defiant refusal to accept racism of any form, including so-called ‘casual’ racism. Kureishi came of age in a Britain where minorities were expected to humbly and gratefully assimilate into the majority culture. This made Kureishi’s lack of deference, and expectation of equality, in his provocative public persona (as well as in his writing), very inspiring.

Hanif Kureishi was born in 1954 in the suburbs of Bromley on the outskirts of southeast London. He was the child of an Indian-born migrant father known as Shanoo and a white British mother named Audrey Buss. From the outset Kureishi’s life-story is intimately bound up with a history of British immigration and social change: the remaking of post-war Britain in the aftermath of decolonisation. As a mixed-race teen, he inhabited a racial fault-line which meant he could not easily claim to be English or Pakistani. This is why he remains fascinated by identity, and belonging and invested in what he calls the ‘brave, un-thought social experiment’ of British multiculturalism.

What is also remarkable about Kureishi’s achievement is that, as a mixed-race teen attending the rough, local state (government) school, conditions for literary talent to emerge were not propitious. He recoiled from academia. Ejected from school with just a few O levels, he almost did not make it to university. Few could have anticipated his remarkable rise from the lower-middle class suburbs to the capital, and subsequent international acclaim with an Oscar-nominated screenplay My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) and a bestselling novel The Buddha of Suburbia (1990). Kureishi came to the fore as an outspoken outsider with a background quite different from the circle of white, privately schooled, Oxbridge-educated men who still tend to dominate British culture.

The young writer came to prominence not only because of his talent, but also because his realisation that his father’s migration and subsequent marriage to his white British mother, and his own upbringing formed a huge, yet still unnoticed, subject. Living through a revolution in how Britain saw itself, Kureishi was the first to show how British-born children of migrants transform what it means to be British. He will be remembered as a writer who redefined Britishness. In his first essay ‘The Rainbow Sign’ (1985), Kureishi ends his powerful indictment of British race-relations with a bold, impassioned insistence that “it is … the white British, who have to learn that being British isn’t what it was. Now it is a more complex thing, involving new elements. So, there must be a fresh way of seeing Britain and the choices it faces; and a new way of being British” (101-2). This was not something widely accepted in mid-1980s Britain.

Kureishi was ahead of his time in confronting racism and especially articulate on its violation of self. His first screenplay My Beautiful Laundrette and autobiographical novel The Buddha of Suburbia became influential cultural milestones in Britain’s adjustment of its self-image as a multicultural nation. Demonised by the right and adored by the liberal left, Kureishi himself became a fulcrum for debates about competing visions of how Britain saw itself. He defined contemporary British multiculturalism as funny, cool, and appealing. As a writer, he is best known for humour and irreverence. He subverted the stereotypes of British Asians. He created an iconography that was both morally serious and playful and mischievous, and has inspired a host of younger writers including Zadie Smith.

Why do we need a biography of Hanif Kureishi when the territory of Kureishi’s life appears so well-mapped in his semi-autobiographical writings by the author himself? And when there are already a few academic monographs on his writing including my own? My biography provides fresh perspectives on Kureishi’s life, work and the contexts that shaped him in three ways. First, I had access to the writer’s unexplored literary archive spanning four decades. I was able to read the diaries he had written since the age of 14, when he decided to become a writer and look at the drafts of all his major works and some unrealised projects. Rather than relying on Kureishi’s memory clouded by the passage of time, these contemporaneous diaries provide access to the mind of the writer: how he felt, responded, and rationalised at the time. The journals bring into focus the shadowy presence behind the stories and curated persona of media interviews. The diaries allowed me to shed new light into the wellsprings and genesis of his writing, and into the development of his creative process: how the life informs the work.

Secondly, I highlight the importance of Kureishi’s south Asian cultural hinterlands. These have been overlooked by white reviewers and collaborators who are more interested in the influence of suburban Bromley, punk, and David Bowie. This is not to say these are not also important contexts, but the focus on British contexts has overshadowed other influences. For instance, my biography traces the little understood but tremendous impact of Kureishi’s first visit to Pakistan at the age of 30. This made him see England afresh. His diary of the visit transforms our understanding of Kureishi and his early films. Similarly, Kureishi’s inheritance from his father’s subcontinental genealogy, Shanoo’s colonial upbringing and immigrant experience, are essential to understanding Kureishi as a writer and as a man. It illuminates Kureishi’s anxiety, but also his self-fashioning, his motivation and extraordinary industry: the ingrained sense of expectation was part of his paternal heritage, compounded by his own ambition. As Kureishi wrote in his diary:

The feeling I had, we had, my father gave me of having to make it in England. We couldn’t go under. I felt this, as a kid, under the strain of racism and that there would be revenge, there would be power. The self-sufficiency of being a writer (Diary 5 April 1989).

Thirdly, as his biographer, I was able to converse not only with the writer himself, but with his family in both Britain and Pakistan and with friends, lovers, and collaborators: most of whom have never spoken publicly about him before. What became clear is that Kureishi was able to overcome the difficulties and inadequacies of his suburban environment and schooling at a rough state school largely because of his literary and intensely competitive father, an aspiring but unsuccessful writer himself. It was his father, Shanoo, who inspired Kureishi’s ambition at a very early age. Furthermore, Kureishi’s educated, talented paternal Pakistani uncles who regularly visited the Kureishi family in Bromley gave him an immediate possibility of a wider world. Kureishi came from a whole family of writers. Concurrently, Kureishi’s focus on his father and male mentors makes the female voices in his life harder to hear. I wanted to do justice to dissenting voices in the Hanif Kureishi narrative. So, my biography traces the influence of the women in his life: those who influenced his literary tastes and political consciousness; their belief in his talent, insights and contribution to his work. Notably, his university girlfriend, Sally Whitman, who politicised Kureishi with her feminist, socialist activism. Subsequently, his former partner, Tracey Scoffield, closely edited his work and helped him discover his singular, playful trenchant voice. His significant relationships with women are vital to understanding who he was in those years: a man who is feminist intellectually, but not always in the way he behaved.

Origins and oppositions

Within the multi-layered story of Hanif Kureishi’s life, I want to focus on the culturally hybrid and seemingly stark oppositions in class and culture that compose his origins. Behind Kureishi’s coming of age in Bromley stands the intertwined history of India and Britain. Ideological forces of empire, colonialism, and partition, with its traumatic legacy and shifting borders, shaped the paternal side of his family. Kureishi’s father Shanoo was born in 1924 in India. One of eleven children, Shanoo came from a cosmopolitan upper-middle-class, urbane, anglicised and educated Indian family.

Shanoo’s father (Kureishi’s grandfather) was a doctor working for the colonial British army. They lived in the new colonial capital of New Delhi designed to showcase British imperial authority with monumental rose-coloured places of colonial government. New Delhi displaced the ‘old’ Mughal city. It represented the racial and social hierarchy of Raj society in its layout. Kureishi’s grandfather, the colonel, bought a palatial, white-washed home in prestigious surroundings near India Gate. It was typical of the grandeur of the imperial city. He called it Al-Kuresh.

Shanoo was educated in an English-medium private school in India and, from the start, was primed for a life abroad. The colonel always wanted his sons to seize educational and economic opportunities that were attracting settlers to Britain. Without inherited wealth, the colonel worked hard to provide his sons with a prohibitively expensive foreign education. Few from the non-white colonies could afford the trip to the ‘mother country’, let alone such an expense. In the 1930s he intended to give his sons an exceptional, formidable head-start in comparison to the rest of the population.

For Shanoo, his privileged subcontinental upbringing became a source of pride when he fell on hard times after moving to Britain and lived a much more frugal life in Bromley. Kureishi would draw on this paternal background of subcontinental privilege too. His wealthy, upper class, confident Pakistani uncles inspired his own portrait of well-heeled British Asians in My Beautiful Laundrette. Moreover, these Pakistani uncles instilled in Kureishi a social confidence. This became particularly important when, as a fledgling writer, he mixed with privately schooled, Oxbridge-educated writers to whom he felt socially inferior because of his own less-privileged state education as his journals reveal.

Shanoo travelled from Bombay to Tilbury on the ship Startheden, to study law at London university. He disembarked in a thin suit amid the drizzle to begin the adventure of his life on 20 December 1947. He was twenty-three. By this time, the colonel – who financed his older sons’ educations – had run out of money for Shanoo’s studies. Unable to finish his degree, Shanoo became a clerk at the Pakistani embassy in London. Shortly after Shanoo arrived in Britain he met and later married a pretty, young English woman from the suburbs. Audrey and Shanoo had two children. Hanif was born in 1954, and his sister Yasmin arrived four years later, born into a Britain when mixed-race marriages were frowned upon and their children viewed as tragic outcasts or ‘half-castes’. Shanoo and Audrey’s backgrounds differed in education and class as much as in culture. Audrey’s parents hailed from the suburban, lower-middle class.

Social class appears almost as large as race in the story of the Kureishi family, with its mix of upper-middle and lower. Kureishi’s maternal grandfather, Edward, was a shopkeeper. Edward sipped pints of Guinness and read the pink racing papers. As a youngster, Kureishi enjoyed visiting Edward’s brother who lived in frugal homes close by, kept pigeons, and had a freezing outside toilet. This ‘pigeon-keeping, greyhound racing, roast beef-eating, and piano in pubs’ strand of British culture of his English grandfather composed the other half of Kureishi’s origins.

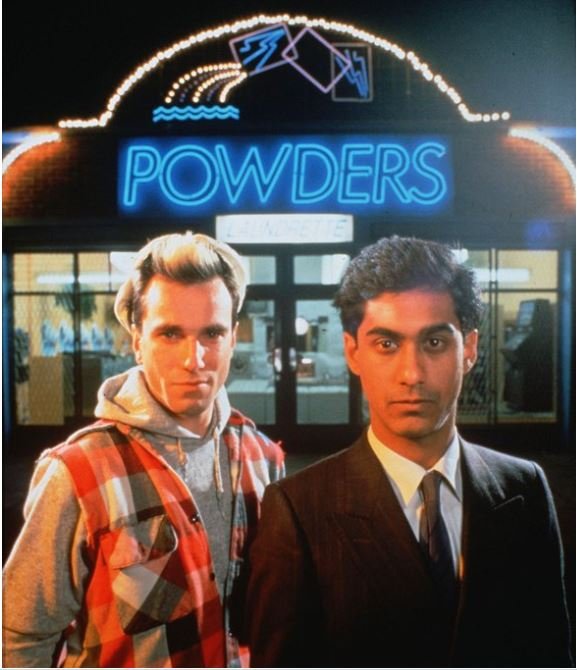

This South Asian/British/upper-middle/lower class mixture gave Kureishi a particular appreciation for the complexity of modern British identity. In his writing, he delights in combining bold oppositions. His breakthrough screenplay, My Beautiful Laundrette, brought two characters – a gay British Asian and white former National Front supporter – you never imagined could be together, in a kiss. It was partly modelled on Kureishi’s own schoolboy friendship. This adolescent friend lived in the deprived council estate nearby and one day turned up at Kureishi’s door transformed into a skinhead. He nicknamed him ‘Bog-Brush’. Using this as a springboard, Kureishi sculpted and embellished this friendship into My Beautiful Laundrette. The screenplay revolves around the unlikely romance between lower middle-class, mixed-race Omar and his old school friend Johnny, a white, working-class, former skinhead and National Front sympathiser now adrift, homeless and broke in Thatcher’s Britain, as they embark upon renovating a dilapidated South London laundrette. Combining bold oppositions is central to Kureishi’s aesthetic. His creative approach continues to couple all kinds of oppositions: fact and fiction, honesty and invention and comedy and sadness.

My Beautiful Laundrette

Race and class in multicultural Britain

What was the social and political backdrop to Kureishi’s father Shanoo’s arrival in Britain and to Kureishi’s own upbringing in 1960s Britain? Shanoo arrived in Britain in 1947, a few months after the Partition of India and just before the British Nationality Act confirmed unrestricted entry to Commonwealth citizens. At this moment, the Empire was still of great political, military, and economic importance and Britain had a notion of itself at its centre. Perceived links to the ‘mother country’ made Britain a natural choice for migrants from Asia and the Caribbean. Britain’s open-door policy was fuelled by its need for labour to service London transport and the new National Health Service. Most notably, the first wave of 492 ‘West Indians’ arrived on the Empire Windrush in 1948. They were famously welcomed as sons of empire on the Evening Standard newspaper’s front page.

However, as Kureishi’s life-story and work trace, the initial welcome to Britain offered to migrants like his father soon turned sour. The new arrivants faced challenges in settling in post-war Britain. They had to address the lack of housing, racial discrimination, the search for dignified jobs, and the open hostility of their new hosts who wanted to ‘Keep Britain White’. Kureishi’s diaries record his father recounting his astonishment on arrival in a bomb-scarred, post-war Britain so different from the image of the glorified mother country inculcated by Shanoo’s colonial education. This surprise becomes the father-figure Haroon’s experience in Kureishi’s autobiographical novel The Buddha of Suburbia. On arrival in the freezing shock of Old Kent Road, Haroon is

amazed and heartened by the sight of the British in England.… Dad had never seen the English in poverty, as roadsweepers, dustmen, shopkeepers and barmen. He’d never seen an Englishman stuffing bread into his mouth with his fingers, and no one had told him that the English didn’t wash regularly because the water was so cold. …. And when Dad tried to discuss Byron in local pubs no one warned him that not every Englishman could read or that they didn’t necessarily want tutoring by an Indian on the poetry of a pervert and a madman. (1990: 24-25)

In Kureishi’s hands, his father’s shock becomes a deft reversal of the colonial gaze.

Decades later in the late 1960s, unemployment and economic hardship fuelled an escalation of vicious racist attacks and the National Front’s violent marches. Kureishi witnessed these demonstrations and would vividly recreate them in The Buddha of Suburbia.

The area in which Jamila lived was closer to London than our suburbs, and far poorer. It was full of neo-fascist groups, thugs who had their own pubs and clubs and shops. On Saturdays they’d be out in the High Street selling their newspapers and pamphlets. They also operated outside the schools and colleges and football grounds, like Millwall and Crystal Palace. At night they roamed the streets, beating Asians and shoving shit and burning rags through their letter-boxes. Frequently the mean, white, hating faces had public meetings and the Union Jacks were paraded through the streets, protected by the police. There was no evidence that these people would go away — no evidence that their power would diminish rather than increase. (1990: 56).

This period coincided with teenage Kureishi’s years at secondary school. It marked a brutal awakening. A fellow pupil, David Goately, who would become the model for the character Charlie in The Buddha of Suburbia remembers:

I had been aware of Hanif since the beginning of the year he joined because, poor guy, he was the only person of mixed-race in a school of 500 boys drawn from a catchment that included some pretty violent council estates and he was picked on because of it. The skinheads, the National Front was just being born and racism was a part of their creed.

This was not quiet, insidious racism, but bullying so extreme Kureishi soiled himself on his first day of secondary school at the age of 11. The sadism of some of the gangs of white boys meant he often returned from school physically wounded: “I’d been locked in a room in the woodwork shop and attacked with chisels and burned in the metal workshop” (My Ear at his Heart 2004: 133). School was a place of fear and torment with packs of adolescents scenting the mixed-raced teen’s vulnerability.

The racism Kureishi encountered during this period was disorienting and debilitating in its brutality and power. Teachers were no better. One humiliated him, insistently addressing him as ‘Pakistani Pete’. Each time, the label ‘Paki’ felt like a slap across his face. The whiplash of racism restructured his understanding of the world. Besieged from all sides: ‘friends, teachers, society’, the teenager concluded in his journal “the identity of a Paki wasn’t worth much” (Diary undated). His father Shanoo had been chased by skinheads on his daily commute to the Pakistani embassy where he worked. Shanoo’s friends in the embassy had suffered racist attacks; leaving Shanoo, a diminutive man, terrified of being kicked to death on the street.

So, he recalls “he resolved to create a new identity, that of an author” (Diary 22 October 1992). The moment he devised a way of escape is crystallised in his memory: “A park on Sunday afternoon in winter walking with the dog” when he planned all he would achieve: “I dreamed of appearing on television & being called ‘a writer’” (Diary 9 February 1992).

My biography traces a mixed-race teen propelled into writing by a deep disenchantment with a Britain that didn’t accept him.The young, highly sensitive teenager keenly resented the racist abuse he suffered at school and on the streets of Bromley.Confiding in his journal, he tried to put his predicament into perspective: “Punished for my brown body, Pakistani father, English mother, I felt each centimetre of their jibes. I am no orphan, no neglected child, but I’ve suffered as if I were a bastard, cripple, lunatic” (Diary undated). The diary powerfully conveys thewarping intensity of his peers’ contempt and a child’s inability to understand and protect himself from it. These psychic wounds radiated and metastasised, forming a rich soil for his writing. He wrote because he had no other outlet. Years later at 30, he avers, “If I had been able to speak to people in the ordinary way, if I hadn’t felt cut off from them, I wouldn’t have bothered writing in the first place” (Diary 15 February 1984). The motivation to write began as “a wish to tell my side of things. I remember having a strong physical sense of wanting to have my say like a defendant in court”.

The climate of racial hostility was made worse by Enoch Powell’s racist hate mongering in the late sixties in the context of the Commonwealth Immigrants Acts (1962 and 1968), which reduced the rights of Commonwealth citizens to migrate to Britain. Conservative MP Powell’s populist, racially incendiary ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech against immigration on 20 April 1968 inflamed the nation: Britain ‘must be mad, literally mad, as a nation’ to be allowing such ‘inflow’. Decades later, Kureishi would refer to Enoch Powell as the “scourge of my childhood” (Diary 6 August 2002). Powell targeted the ‘native-born’ like the fourteen-year-old Kureishi who, Powell worried, would ‘constitute the majority’ of the ethnic minority population in a few decades. In the wake of Powell’s words widely reported in the newspapers, thousands turned out on the streets to support him and his attack on non-white British citizens whom he referred to as a national danger. ‘We want Enoch’ rang from street corners across the country from the mouths of ordinary people including dockers, car workers, and immigration officials from Heathrow, in addition to the National Front. For the teenaged Kureishi, Powell’s speech marked a key moment. It legitimised everyday contempt and unexamined racism and intensified verbal and physical abuse. Kureishi’s compelling autobiographical essay ‘The Rainbow Sign’ traces its impact. At first “graffiti in support of Powell [‘Enoch for PM’] appeared in the London streets. Racists gained confidence. People insulted me in the streets. Someone in a café refused to eat at the same table as me”. School-friends’ parents began “talking heatedly and violently about race”, nodding vigorous support for Powell and repatriation in his midst, leaving the teen reeling with disorientation. Suddenly there were homes he was no longer allowed to enter, including that of his first white girlfriend. His schoolmates now declared “We’re with the NF” (1985: 75-6). Decades later he would tell me, “The pain of that period in the mid-1960s is still with me”.

Scarred by the cruelty of his contemporaries, with violence and menace part of the social landscape of his late teens, it is hardly surprising that Kureishi grew up with a lasting sense of precariousness beneath social relationships. In his diary, at the age of twenty he reflected on his paranoid tendencies: “racism gives you a suspicion of people, lack of confidence” (Diary 30 March 1991). Not only did the trauma provoke him into writing, but it also shaped his personal and political perspectives as a writer. The betrayal of his peers would impel his aversion to groups and scepticism of collectivism, but also his non-conformist vision. Being labelled a ‘Paki’,’ and a ‘mongrel’ and having identities imposed upon him rendered him extraordinarily sensitive to how language and discourse shape human behaviour; how thought is made and constrained by language. But this experience as a mixed-raced youth also gave him a unique insight into both sides. He knew what it was like to be on the receiving end of racism, but equally important, is his understanding (as explored in My Beautiful Laundrette) of the boys he grew up with and the conditions that fuelled their racism: unemployment, despair, and hypermasculinity that has enduring significance in today’s Britain.

The 1970s was also a time of resistance to overt racism with the formation of antiracist groups, notably the Anti-Nazi League and Rock Against Racism. These inspired other individual creative acts of resistance. Kureishi’s came in the form of subverting stereotypes of Asians. His Asian characters were not victims, but funny, feisty, and often morally complex and dubious. His weapon was his sly humour evident in the memorable opening to The Buddha of Suburbia mediated through mixed-race teen narrator Karim, a Kureishi-like figure:

My name is Karim Amir, and I am an Englishman born and bred, almost. I am often considered to be a funny kind of Englishman, a new breed as it were, having emerged from two old histories. But I don’t care — Englishman I am (though not proud of it), from the South London suburbs and going somewhere” (1990: 3).

This much-quoted beginning, highlighting fluid post-imperial identities and the interplay between race, place, and nation, would usher in a flurry of popular novels about multicultural Britain. The narrator’s defiant good humour is characteristic of Kureishi but, as we have seen, laughter blunts the jagged edge of deep wounds endemic to his work.

As well as overt racism, Kureishi also targeted subtle forms of racism. The Buddha of Suburbia traces Karim’s escape from the suburbs for theatrical and sexual adventures in London. It draws heavily on Kureishi’s own trajectory as he became a budding playwright in London. Through the directors Karim/Kureishi meets in his adventures in theatre, the novel lampoons the insidious cultural racism of the arts world that Kureishi experienced as a young playwright. The novel parodies the radical director who forces young mixed-race Karim to blacken his creamy skin with “shit-brown” makeup and wear a loincloth to play Mowgli so he ends up looking like “a turd in a bikini bottom” (1990: 146). The novel lampoons the director Shadwell who wants to impose a ‘destiny’ on Karim as a “half-caste… belonging nowhere, wanted nowhere” (1990: 141).

As the 1980s ended, other issues would dominate British race-relations. In particular, the fatwa against Salman Rushdie for his novel The Satanic Verses in 1989 and the ensuing book burnings in Pakistan, London, and elsewhere. Kureishi found himself at the centre of the wars between cultural respect and freedom of expression because of his steadfast support for his close friend Salman Rushdie and their fearless insistence on freedom of expression. Kureishi was particularly clairvoyant on the rise of British Muslim fundamentalism. He identified some British Muslims’ alienation long before 9/11 and the London bombing of 7 July 2005. He would write a novel The Black Album (1995) and screenplay My Son the Fanatic (1997) on this subject.

To conclude, the eruption of far-right, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim violence across Britain this summer underlines the enduring significance of Kureishi’s sustained engagement with migration, multiculturalism, ‘Britishness’, and ‘belonging’ over the last forty years. In the context of resurgent narrow nationalism and intolerance, when the very idea of multiculturalism is under siege, public-facing engagement with a cultural figure such as Kureishi is more important than ever: these questions have never been so contested. Just after the eruption of anti-migrant violence in Britain in July 2024, Kureishi posted his response, his insight informed by his unique perspectives:

The so-called mindless thugs out on the street this week destroying shop fronts, torching cars and attacking mosques are some of the most neglected, disaffected people in the U.K. They are vulnerable insofar as they are not integrated into the country’s economic model, having no stake in the culture, no High Streets and no future. The white working class have good reason to riot, except that their aggression is facing in the wrong direction. Without leadership or ideology, authentic desire for political representation morphs into pointless violence.

Typically, the bully orients himself around a more defenceless target, whom he can persecute without fear of retaliation. Migrants aren’t, as it is often said, ‘taking your jobs’; there are no jobs. The thug is now as insecure as the migrant, they are both adrift, and it is this identification that fuels the aggression. (The Kureishi Chronicles 10 August 2024)

Over the past decades Kureishi has continued to write and intervene in public debates. He welcomed Black Lives Matter and the shift #MeToo created and condemns the backlash against the #MeToo movement, notably the attempts to characterise it as puritanical. Unsurprisingly, Kureishi remains wary of any cultural swing towards homogeneity or censorship. He opposes ‘cancel culture’. Instead, he wants to shift debate through argument, culture, and discussion.

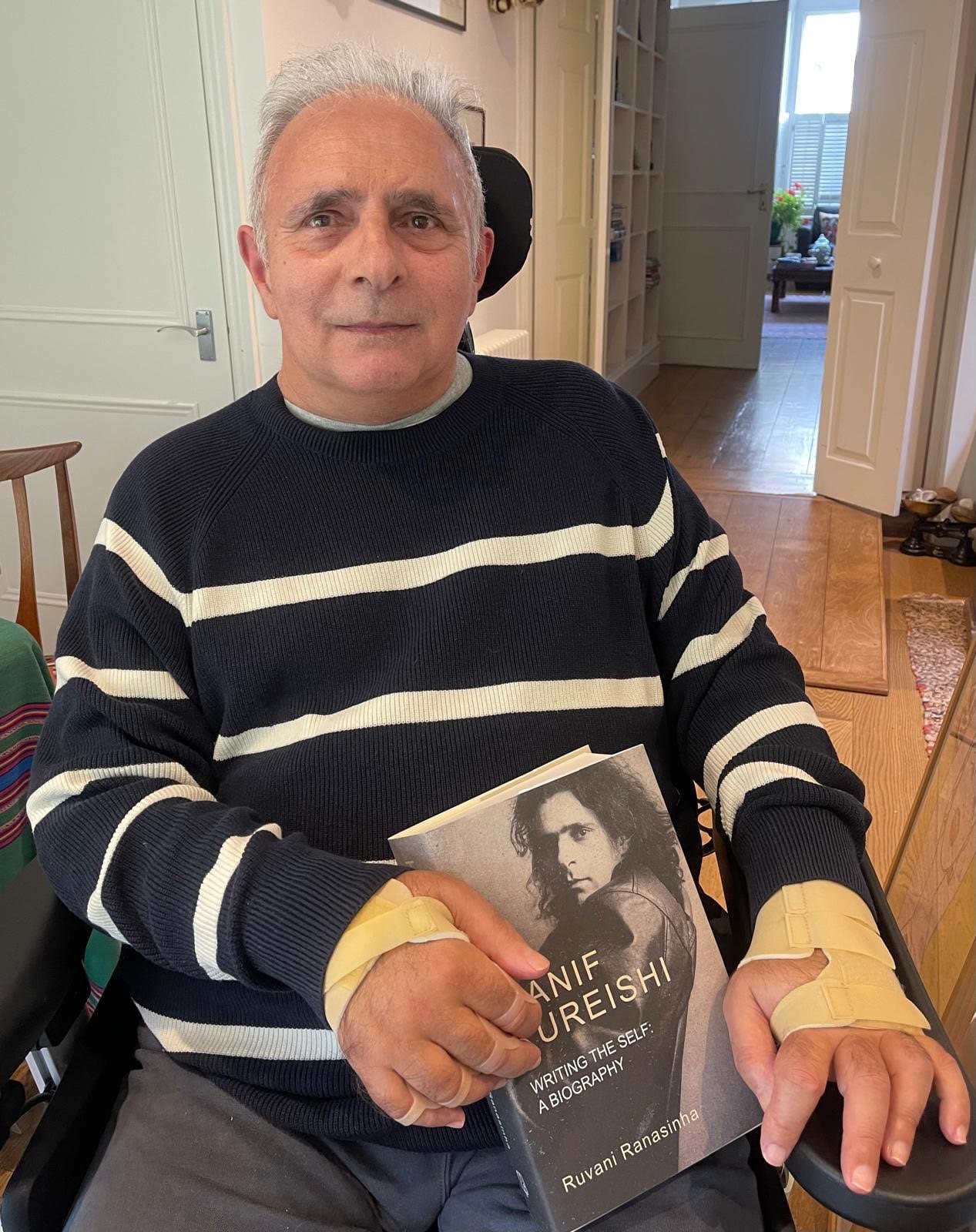

I had intended to end my biography with this tribute to Kureishi’s enduring relevance and ability to chronicle and comment on Britain’s shifting socio-political trends. But very sadly, circumstances compelled a very different afterword. On Boxing Day 2022, a few weeks after his sixty-eighth birthday, Kureishi felt dizzy after taking a walk on holiday in Rome. He collapsed in his apartment, injuring his spine. The injury has left him completely paralysed from his neck downwards. His mind remains sharp and lucid. In a series of dictated tweets, he began to recount his terrifying, devastating experience of becoming paralysed. Just as he transformed the horrors of race into comedy, he turns his life-changing injuries into moving prose. He has recently published a memoir about his accident, aptly named Shattered (2024). There are some slight improvements in his hand movements, but it seems that he will remain in a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Kureishi today

Ruvani Ranasinha is Professor of Global Literatures at the Department of English, King’s College, London. She was a jury member of the Gratiaen Prize 2023 awarded annually for the best work of creative writing in English by a Sri Lankan resident in Sri Lanka.

Image credit: Ruvani Ranasinha

Notes

[1] Hanif Kureishi: Writing the self: A biography by Ruvani Ranasinha is available at www.amazon.co.uk/Hanif-Kureishi-Writing-Ruvani-Ranasinha

[2] Editors’ note: This talk was delivered in-person at the International Centre for Ethnic Studies, Sri Lanka in Colombo on August 22, 2024. It has been lightly edited for publication.

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...