Contingence, Conjuncture and Structure: The Economic Crisis in Sri Lanka

Sumanasiri Liyanage

Prologue

Vice-Chancellor; Deputy Vice-Chancellor; Dean, Faculty of Arts; Head, Department of Economics; members of Prof. H. A. de S. Gunasekera’s family; colleagues, friends, and students.[1]

It is indeed a pleasure to be in Peradeniya once again, and I felt honoured and privileged when I was asked to deliver the Professor H. A. de S. Gunasekera Memorial Oration 2025, for which I thank Prof. Sri Ranjith, Head of the Department of Economics, and other members of the H. A. de S. Gunasekera Memorial Committee.

Let me begin with a brief anecdote. My first face-to-face meeting with Prof. Gunasekera took place in the latter part of 1966, when I came to Peradeniya to do a special degree in economics after spending the first year at the University of Ceylon, Colombo. However, that was not my first encounter with him. I remember three previous encounters, though not face-to-face meetings.

The first was in March 1960, a year in which I was thrown into the periphery of left politics in Sri Lanka. As a village lad, I walked from house to house with the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) candidate for the Baddegama seat in the 1960 March parliamentary election distributing his leaflets. In the same election, I found Dr. H. A. de S. Gunasekera contested the Borella seat as the LSSP candidate. So, I had heard his name not as an economist, but as a samasamajist.

In the early 1960s, the chair of economics fell vacant as Professor B. B. Das Gupta of Indian origin retired. Who will be the first Sri Lankan chair of economics, became an issue of national importance. There were two contestants, Dr. F. R. Jayasuriya and Dr. H. A. de S. Gunasekera, both from the teaching staff of the Department of Economics. I was in the GCE A/L class at the time, and together with many of my friends I supported Dr Gunasekera because he was a samasamajist and leftist. There was an intense campaign. At that time, these kinds of appointments were made by the senate of the university that had representation from the parliament. Mr. Dudley Senanayake and Dr. N. M. Perera voted for Dr. Gunasekera and Mr. Philip Gunawardena voted for Dr. Jayasuriya. Dr. Gunasekera was finally appointed the first Sri Lankan chair professor of economics.

My third encounter was in 1964. Dr. N. M. Perera, one of the most popular leaders of the LSSP proposed to the central committee of the party that the LSSP should form a coalition government with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) headed by Mrs. Sirimavo R. D. Bandaranaike, the prime minister. A special conference was convened to decide on the matter where two more resolutions were added. While the second resolution opposed any kind of coalition with a bourgeois party characterising it as a betrayal (in spite of the SLFP adopting some radical measures like nationalisation), the third resolution proposed that the LSSP could join a coalition government but along with the other two left parties. Among the signatories to the third resolution were three Peradeniya dons, Mr. Doric de Souza, Dr. Osmund Jayaratne and Prof. H. A. de S. Gunasekera.

I referred to these anecdotes as they open a window to enter the subject that is the theme of my talk this evening. I consider Prof. Gunasekera as a political economist although the term was not in vogue during that period.

How do we distinguish political economy from mainstream economics that has become ‘normal science’ in Kuhnian (1962) terms? Mainstream economics, that the late John E. Weeks (2014) called “fakeconomics” comes from different modes: neoclassical, supply-side, rational expectations, and neoliberal. Weeks defines ‘fakeconomics’ in the following words:

Fakeconomics is the study of exchange relationships that have no counterpart in the real world and are endowed with metaphysical powers. These exchanges are voluntary, timeless and carried out by a large number of omniscient creatures of equal powers. These creatures know all possible outcomes and the likelihood of every exchange, so they are never surprised (they are omniscient, after all). In fakeconomics no difference exists among the past, present and future, and full employment always prevails. (7)

Political economy, however, proposes to examine an economic phenomenon, situating it in its social, political, cultural. and psychological setting. As Franklin Roosevelt once said, “We must lay hold of the fact that economic laws are not made by nature, [but] made by human beings” (quoted in Weeks 2014: 17). Pure economic theory that abstracts from a specific social structure is impossible. Prof. Gunasekera was a political economist. Moreover, it is correct to say that almost all the teachers in the department during that time were political economists. I wish specially to mention a few names: Prof. B Hewavitharana, Dr. K. H. Jayasinghe, Dr. Ian Vanden Driesen, Prof. Balakrishnan, and Prof. ‘Tawney’ Rajaratnam. Studying under these doyens was not only a memorable but also a pleasant experience, although almost all the lectures were held in the dilapidated takaran (tin) building. They were great teachers and had a passion to instil knowledge in their students.

In this talk, I intend to pay my tribute to Prof. Gunasekera as a political economist by adopting the method of political economy to the subject under review.[2]

Introduction

If one wants to harvest quickly,

one must plant carrots and salads;

if one has the ambition to plant oaks,

one must have the sense to tell oneself:

my grandchildren will owe me this shade”

~ Léon Walras

There has been a general agreement that Sri Lanka experienced its worst economic crisis since independence in 2020-23 notwithstanding the fact that there has been no consensus regarding its causes. Proper understanding of the crisis and its underlying causes requires the crisis to be located in its spatial, temporal and global context. 2020 may be defined as a year of generalised crisis in the global capitalist system marked by triple crises – epidemiological, ecological, and economic – with no definite sign of recovery as yet. In some countries, including Sri Lanka, these triple crises are associated with a political crisis leading to quadruple crises.

Mainstream economists describing the economic crisis in 2020 a posteriori would say that it was caused by the COVID19 pandemic and the state’s fiscal mismanagement, all ‘exogenous factors’. However, careful analysis of world economic data demonstrates that the recovery of the world economy from the 2006-08 recession was mild and the growth was sluggish. Moreover, the world economy began to experience a decline in 2019 – well before the COVID19 pandemic hit. Of course, the crisis was exacerbated by the epidemiological crisis, although it was not triggered by it. As Anwar Shaikh (2011) notes, “Capitalist accumulation is a turbulent dynamic process. It has powerful built-in rhythms modulated by conjunctural factors and specific historical events” (44).

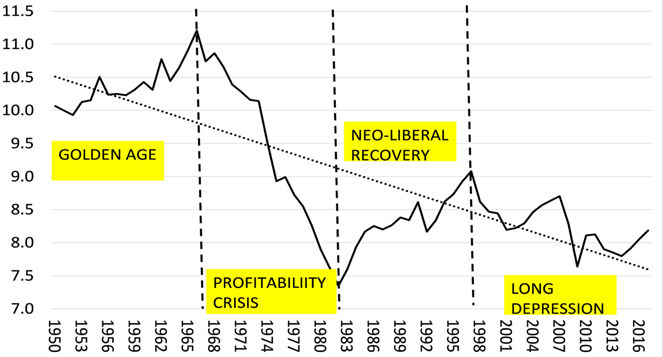

There has been a general consensus that the engine that drives investment is profit. Or, as Marx has informed us, it is the rate of profit of enterprise that is equal to the rate of profit minus rate of interest that drives capital accumulation. Figure 1 shows the behaviour of the rate of profit in G-20 countries from 1950 onwards. The diagram divides the post-World War 2 period into four main phases in terms of the main trends of the global rate of profit.

From the end of World War 2 until the early 1970s, the rate of profit was rising in G20 countries and remained at a high level. During this period, the growth rate of both developed and underdeveloped countries was around 5%. The first slump that began in 1974-75 and exacerbated by the oil price hike was marked by a significant reduction of the rate of profit and the rate of growth. This crisis paved the way for neoliberal policies, the notable feature of which was to keep the wage rates below the rate of productivity growth, so that the profit share of the bourgeoisie substantially increased. However, the honeymoon of neoliberalism began to end in the early 2000s, culminating in the 2007-08 financial crisis.

Figure 1: Rate of profit in G20 countries (in %)

Source: Calculated by Michael Roberts using World Penn Tables. https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2020/09/20/

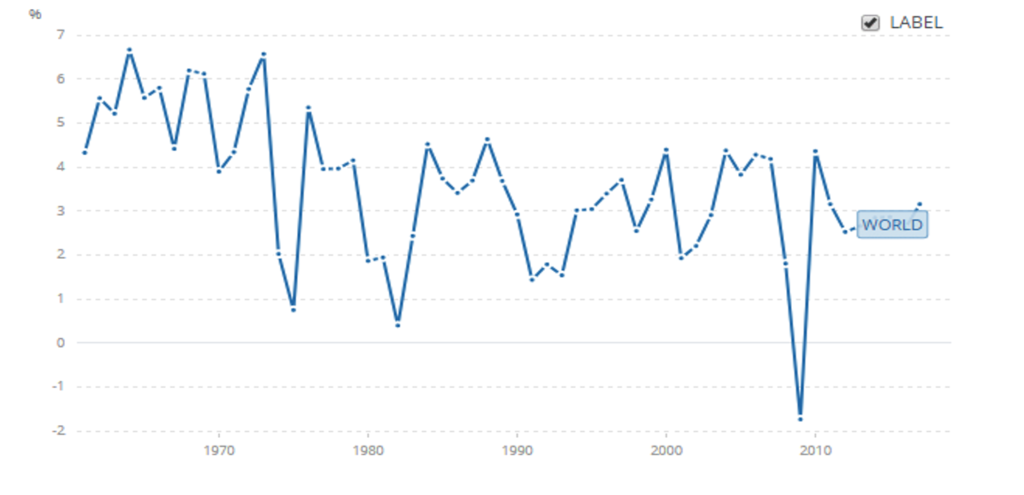

Figure 2 shows the fluctuation of the growth rates of the global gross domestic product (GDP) in the last 60 years. Since the rate of profit, or more exactly the rate of profit of enterprise, is the principal determinant of capital accumulation, and the rate of growth of GDP in turn directly relates to capital accumulation, some correspondence between Figures 1 and 2 may be seen.

Figure 2: World GDP growth rates, 1961-2018 (annual %)

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG for 1961-2018

Anwar Shaikh (2016) has identified particular mechanisms through which order and disorder, i.e., equilibrium and disequilibrium, are intimately related. According to him, “[t]his is the system’s mode of turbulent regulation, whose characteristic expression takes the form of pattern recurrence” (5, emphasis in original). The two modes of turbulent regulation Shaikh identified are: (1) regulation through price and quantity changes through market mechanisms of so-called invisible hand; and (2) turbulent macro-dynamics that determines cyclical behaviour of the economy through bouts and booms (2016: 5-6). Having taken into consideration the works of other writers on the subject, a somewhat different listing of upswings and downswings, of varying temporality and amplitude such as inventory cycles of 3- 4 years and business cycles of 7-8 years, may be identified. Nonetheless, my reference here focuses on the overlapping of different crises with different time periods.

Since the early 1970s, there has been a revival of the notion of long waves in economic life. The cycles popularly known as Kondratieff cycles following the contribution by a Russian economist, Nikolai Dmitriyevich Kondratiev, re-entered the cycle discourse in explaining the long post-World War 2 boom. Nonetheless, the idea of long cycles was originally proposed by Parvus, a Russian Marxist. In 1901, he published a pamphlet giving a bare outline where he noted that capitalism, after a long expansion, would reach a point at which it would exhaust its development potential. Ernest Mandel (1995) advanced the theory of long cycles in a rigorous Marxist framework in the early 1970s in which he emphasised the importance of political factors in explicating upward turn after a trough.

Three principal theses

This oration is woven around three main theses that in my view are demonstrable propositions. My first thesis is that the crisis in Sri Lanka (2020-24) was an outcome of the simultaneous presence of three crises that are overlapping and over-determining. These three crises are the structural or organic crisis, the periodic or conjunctural crisis, and the contingent crisis. My second thesis refers to neoclassical economics. In its multiple versions, neoclassical economics has failed to get underneath the tempestuous surface of capitalism, therefore, a new heterodox theory with the concept of real competition at its centre is needed in order to identify the central tendencies of the system. The 2022 combination of economic crisis with political turmoil should be read as a ‘moment’ in a long process that began with the introduction of the so-called ‘open economy’ reforms in 1978 that created a situation which pits capital against labour, labour against labour, and capital against capital. Hence, my third thesis reads: The outcome of the process (capitalist development or non-development or truncated development) is invariably predicated by the way in which these struggles, inter-class as well as intra-class, are concretely contested.

Definitional distinction

The crisis is defined here as a rupture in the process of production and reproduction. Let me first turn to these three main terms: the structural or organic crisis; the conjunctural or periodic crisis; and the contingent crisis. How, and in what way, are they different from each other? What is the definitional difference?

In addressing these two related questions, the methods deployed by Marx may be useful. As Daniel Bensaïd (2009) has shown, Marx proceeds not by definitions (enumeration of criteria) but by the determination of concepts (productive/unproductive, surplus value/profit, production/circulation), which leads towards the concrete as they are articulated within the totality” (97, emphasis added). Similarly, Raymond Williams (1977) suggested that when taking up a definition, one should start with basic social practices, not fully formed concepts. He called for an etymology based on social as well as intellectual history because the meaning of ideas is forged in concrete social practices (11-12).

Thus, to understand the distinction between “organic” and “conjunctural”, it is advisable to relate them to a real historico-political situation. As Antonio Gramsci (1971) noted, “a common error in historico-political analysis consists in an inability to find the correct relation between what is organic and what is conjunctural” (178). For him, organic movements are relatively permanent while a conjunctural phenomenon appears as occasional, immediate, and almost accidental (177). Nonetheless, he did not mean that the conjunctural disequilibrium is exogenous to accumulation dynamics of the capitalist system. The Gramscian notion of organic crisis has a close affinity with the notion of structural crisis delineated by Istvan Meszaros (2010: 680-81). The structural or organic crisis, because of their creeping character, may be distinguished from cyclic or conjunctural crisis, that according to Marx came as “thunderstorms”.

In this sense, conjunctural disequilibrium, the origin of which lies in the dynamics of capitalism itself, shakes out over- capacities either in inventories or in production. It is neither unnatural nor illogical to see the capitalist system as a crisis-ridden one. On the contrary, overcoming the structural crisis of the capital-system necessitates a solution that goes beyond capital. This system’s inherent tendency towards disequilibrium is brilliantly depicted by Anwar Shaikh (1978) in the following words:

[Capitalist society] is a complex, independent social network, whose reproduction requires a precise pattern of complementarity among different productive activities: and yet these activities are undertaken by hundreds of thousands of individual [or corporate] capitalists who are only concerned with their private greed for profit. It is a class structure, in which the continued existence of the capitalist class requires the continued existence of the working class; and yet no blood lines, no tradition, no religious principle announces who is to rule and who is to be ruled. It is a cooperative human community and yet it ceaselessly pits each against the other, capitalist against worker, but also capitalist against capitalist and worker against worker.

He continues:

The truly difficult question about such a society is not why it ever breaks down, but why it continues to function. In this regard, it is important to realize that any explanation of how capitalism reproduces itself is at the same time (implicitly or explicitly) an answer to the question of how and why non-production occurs and vice versa: in other words the analysis of reproduction and the analysis of crisis are inseparable. (219, emphasis in original)

These conjunctural disequilibria with varying temporality and amplitude may take the form of either a disproportionality crisis or of an underconsumption crisis, or an overproduction crisis (Mandel 1977). The greatest heterodox economist of the twentieth century, John Maynard Keynes (2013), has shown in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, that the equilibrium is not the general state of the capitalist system. For him, the equilibrium is conjunctural in the above sense, and there is no deus ex machina (Adam Smith) or tậtonnement process (Léon Walras) that ensures an equilibrium solution.

In contrast to conjunctural disequilibrium, the organic crisis signifies that the system in its totality can no longer go on preserving and maintaining its principal features. The global economy since 1820 had gone through such crises during 1847-48, 1873-74, 1929-33, 1974-75, and has once again been in such an organic crisis marking the inevitable end of the neoliberal phase (1980- 2020?). Gramsci (1971) termed “this sort of concatenation of crises ‘organic’ insofar as they threaten the very foundations of capitalist stability … [A] crisis can be called ‘organic’ when cracks begin to appear in the very edifice of bourgeois rule” (177-8). According to Stuart Hall (1988), “An organic crisis is not some chance happening in which all of the various cosmic crises align; it’s rather what happens to hegemony when capitalists as a class fail to maintain it” (12).

Levenson (2020) further elaborates:

For Gramsci, capitalist rule is secured by what he called “hegemony”. Capitalists as a class have successfully convinced the rest of us that their own particular class interest – maximizing profit – is in the interest of the rest of us. Think of the way we talk about the economy: business confidence is invoked as a measure of economic health, even though it doesn’t alter the fact that wages have remained stagnant for decades despite productivity gains. We conceive of abstract measures like “economic growth” or “GDP” as somehow corresponding to the common good – even though these figures tell us nothing about inequality or the well-being of the working class.

An organic crisis occurs when this bourgeois claim to universality begins to crumble, and previously hegemonic assertions are revealed for what they truly are: means of securing capitalist stability. The social consensus, in other words, deteriorates, and capitalist claims no longer appear to correspond to the general well-being. This is when those famous “morbid symptoms” begin to appear.

A few words on contingent crisis may be relevant. To my knowledge, the category of the contingent crisis was first developed by Prabhat Patnaik (2022). I quote him at length below:

The problem with all these [mainstream editors’] explanations however is that they completely ignore the role of neo-liberalism in precipitating the Sri Lankan crisis … Under neoliberalism, apart from the distress of the working people even in the best of times, apart from the structural crisis [and periodic crisis] arising from the increase in the share of economic surplus in output in every economy, and in the world economy, there is a third kind of crisis that particularly affects small economies, whose fortunes can change in the fraction of a moment. I shall call this the ‘contingent crisis’ unleashed by neoliberalism. It is ‘contingent’ as opposed to structural [and periodic] because it affects not the world economy as a whole, nor even a huge swathe of it, but particular countries that happen to get caught in it at certain times. A hallmark of it is that wisdom invariably comes to everyone after the event. (emphasis added)

The best example is the economic crisis in Greece. Greece had piled up a huge amount of external debt, but the debt did not immediately appear unsustainable. The irony is that “when debt did appear unsustainable, the economy had already gone beyond salvaging without a debt write-off”. Prof. Patnaik further notes contingent crises “are not accidental phenomena; they are intimately and organically linked to the neoliberal regime”.

Crisis in Sri Lanka, synchronising three levels of ailments?

In the remaining part of the talk, I shall deal with the Sri Lankan economy in the last forty-six years (1978-2024). As Sri Lanka had been integrated into the global economy in multiple ways during this period, it is natural that the country cannot escape the vicissitudes of the global economy. As a necessary corollary of this integration, Sri Lanka is now going through quadruple crises: epidemiological, ecological, economic, and political. A crisis of this sort – i.e., the confluence of crises in nearly every sphere – may be easily defined as an organic crisis. Although the organic crisis as a crisis of hegemony has many facets, here the concern is limited to only its economic dimension and how it has been associated with periodic and contingent elements of the crisis.

A concrete analysis of this nature poses two problems. Firstly, the statistical categories that have been used in official data are quite distinct from the analytical and statistical categories deployed by me in the course of this talk. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines GDP as “an aggregate measure of production equal to the sum of the gross values added of all resident and institutional units engaged in production and services (plus any taxes, and minus any subsidies, on products not included in the value of their outputs)” (2008: 236). An IMF (2020) publication states that, “GDP measures the monetary value of final goods and services—that are bought by the final user—produced in a country in a given period of time”.

On the one hand, the basic problem of these conventional accounting systems is that they classify many activities as production when they in fact should be classified as forms of social consumption. The approach of the classical tradition, on the other hand, emphasises the distinction between production and non-production activities (Shaikh and Tonak 1994: 2-3). In many advanced countries, it is customary to classify a distinct category called output of the manufacturing sector that may be taken as a more reasonable and realistic estimate of production in the economy. However, such a classification does not exist in Sri Lankan data.

Secondly, as Friedrich Engels (1969) notes, “[a] clear survey of the economic history of a given period is never contemporaneous: it can only be gained subsequently, after collecting and sifting of the material has taken place. Statistics are a necessary help here, and they always lag behind” (186). The conceptual differences in the presentation of data in various annual reports of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka also make comparison somewhat difficult. For example, in the late 1980s, GDP was made a prominent category in place of gross national product (GNP).

Another controversy would arise on the issue of the temporal dimension of the crisis. Colombage (2024) writes: “Following the imprudent economic policies adopted during the period 2019- 2022. Sri Lanka fell into a deep economic crisis”. However, he writes on the same page that the roots of the crisis go beyond 2019. “The current economic crisis is the culmination of internal and external macroeconomic imbalances experienced over the decades” (xv). In my view, he is correct on both accounts, but the crisis he referred to seems to be limited to the ‘contingent’ end of the crisis. The crisis that erupted in 2020-22 was a classic example of a contingent crisis. Although the eruption of the contingent crisis may look sudden, it is as Prof. Patnaik has highlighted closely and intimately linked with the periodic and the structural levels of crisis to which I would turn presently.

Figure 3: Three levels of crisis

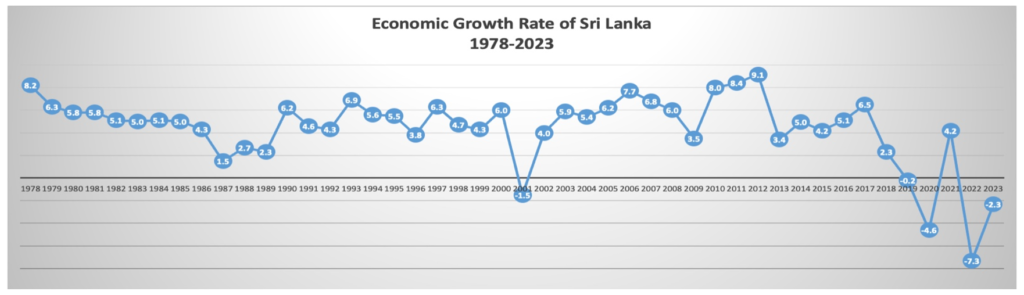

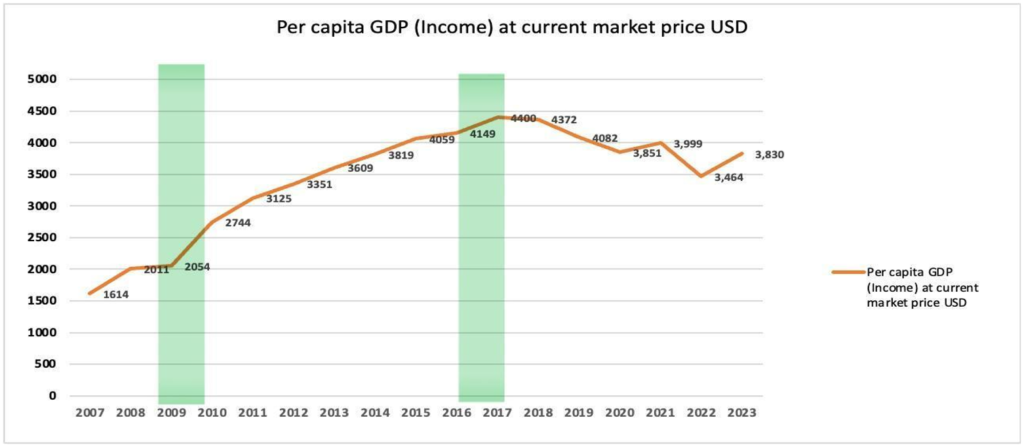

Periodic crisis began in 2016 after the burst of the ‘infrastructure bubble’ and the contingent crisis erupted within this recession (2016-21). Figure 4 shows that right now Sri Lanka is going through a contracting W-shaped crisis. Figure 4 in its entirety addresses this phase of the structural or organic crisis that lies as the foundation for other two crises (Figure 3), conjunctural and contingent.

Many tend to believe that the country took a credible policy shift in 1977 with the change of regime. The election of 1977 gave a massive mandate to the United National Party (UNP) led by J. R. Jayewardene, and that victory was interpreted by many as a rejection by the Sri Lankan voters of economic policies adopted by the coalition government consisting of the SLFP, the LSSP, and the Communist Party of Sri Lanka (CPSL).

The coalition government of 1970-77 adopted basically an inward-oriented economic policy, partly because of the adverse international situation marked by the global economic slump, oil price hike, and the substantial drop of agricultural production. Besides, the LSSP, the CPSL, and the left wing of the SLFP had strong leanings towards socialist economic planning as a model of development for third world countries. Nonetheless, the economic deterioration marked by a high level of unemployment had led people to move away from the coalition government in the parliamentary election of 1977.

The economic strategy that the Sri Lankan government introduced in 1977 was very much closer to the policy strategy developed in the late 1970s, that later became popularly known as “the Washington Consensus”, and to the economic policies adopted by the Pinochet government in Chile after the military coup overthrowing the elected President Salvador Allende. One may even wonder whether the imperialist countries of the Global North used Sri Lanka as a laboratory to test whether the neoliberal policies articulated by the ‘Chicago Boys’ could be practiced in a less authoritarian context with formal democracy. Sri Lanka was an ideal guinea pig for such an experiment.

The outward-oriented economic strategy was presented as a panacea for all the economic ails of the countries of the Global South when the opposition UNP promised to make Sri Lanka a Singapore or the Republic of Korea. Although the country has not yet been able to even come closer to South Korea, not to mention Singapore, after nearly five decades of anti-dirigisme policies, many observers argue that Sri Lanka is now better-off having followed the so-called outward-oriented economic policies. I argue that this perception depends more on myth than on reality.

One of the myths is that the 1978 policy package has contributed to accelerate economic growth after a sluggish growth performance under the inward-oriented strategy with explicit social welfare bias. Actually, what happened was the replacement of the period of slow growth of the sixties and the early seventies by a period of sluggish growth with occasional upswings and frequent downswings. During this 46-year period of outward-oriented policies, the rate of growth exceeded the magical 7% level only in six years. The most important and critical issue is not achieving a high rate of growth, but the economy’s capacity to sustain the continuity of the process.

Sri Lanka was able to maintain a growth rate of above 5% for a continuous five-year period in only two clusters of years during this period, namely, during 1978-82 and 2003-07. The second cluster may be extended until 2012 with the growth rate slowing down during the intensified internal armed conflict in 2008 and 2009, but bouncing back after the military victory of the security forces over the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. Both these clusters are characterised by state-led infrastructure investments. Infrastructure investments during 1978-82 were financed by lucrative and generous foreign grants and concessionary loans; while the second wave of infrastructure developments were financed by high interest bilateral loans and the sale of international sovereign bonds in the global capital market.

As Figure 4 shows, regular fluctuations in the percentage rates of growth convey the impression that a growth dynamic was not embedded in the 1978 policy package despite isolated years of prosperity. Therefore, one may argue that the future is likely to be bleak if the same policies continue. As W. A. Wijewardena (2020) noted in one of his regular columns: “Sri Lanka has now been downgraded from a higher middle-income country to a lower middle-income country on account of its poor economic performance in 2019. With the economic downfall arising from the COVID19 pandemic, Sri Lanka is going to live in this lowered status at least in the next few years. Thus, it has been a stumbling block for the country to reach its goal of becoming a rich country in a single generation”.

Figure 4

Source: Central Bank annual reports (various issues)

As Figure 5 reveals, it has taken twenty-six years for per capita income to reach the 1000 USD mark in Sri Lanka. The per capita income in South Korea was 109 USD in 1965, and it exceeded the 1000 USD mark in just twelve years (by 1977). In Sri Lanka, the clusters of years with reasonably higher growth rates were an outcome not of an activation of the logic of capitalist development, but rather a result of exogenously-funded infrastructure development projects. Infrastructure investment injects new resources into the economy, thereby boosting the rate of growth. Yet its impact on capitalist accumulation may not be strong. On the contrary, as Figure 6 shows, infrastructure projects with long gestation periods have created a massive foreign debt problem as shown by the high ratios of debt servicing to the GDP.

Figure 5

Source: Central Bank annual report (various issues)

Figure 6: Annual growth rate and foreign debt

Source: Daily FT, 17 August 2020.

How do we elucidate the fact that the two waves of state-led infrastructure development failed to generate in itself a growth momentum in the economy? Why hadn’t it become a boon to the growth of the private sector? These two questions are related to a wider question: Why did Sri Lanka fail to achieve capitalist development in the last 75 years since independence? Prior to 1977, a simple if not a simplistic answer was offered to this question. The answer was that the blame should be attributed to the dirigisme regime guided by a social welfarist ideology. According to neoclassical development logic such a strategy was inherently bad for growth and development. Notwithstanding the fact that this argument is not supported either by historical evidence or by logical reasoning, I propose to bracket it for the discussion here as the focus of the current discourse is on the post-1977 phase of Sri Lankan economic history.

Since 1978, every regime that has ruled the country (including the present government) has openly accepted the capitalist path of development. Why didn’t the paradigmatic shift of 1978 produce an intended outcome although there is a consensus on the potential success of open economic policies?

The following checklist attempts to summarise the principal elements of the crisis architecture as outlined by orthodox economists, think tanks, and multilateral agencies.

- Inadequate trade liberalisation and an anti-export bias;

- Non-compliance with fiscal rules and deficit financing with non-productive social expenditure;

- Non-independence of the Central Bank;

- Rigid and non-flexible exchange rate policies;

- Inadequate State-Owned-Enterprises reforms.

These five inadequacies that had led to developmental failure, according to neoclassical economists, were a necessary outcome of two causes, namely: (1) not enough liberalisation and (2) excessive state intervention. By rephrasing Marx’s often quoted and resonant passage from Capital Vol. 1, the neoliberal solution to the sad status of the Sri Lankan economy may be summarised as: “[Liberalise, liberalise!] That is Moses and the prophets! … [liberalisation] for the sake of [liberalisation], production for the sake of production: This was the formula in which [neoclassical] economics expressed the historical mission of the bourgeoisie in the period of its domination” (1976: 742).[3]

Neoclassical economists may always find solace by saying that it was not neoclassical economics that failed but the inadequate dose of its application. However, I do not mean that there is not an iota of truth in the neoclassical explanation. Neoclassical economists explicitly or implicitly refer to non-productive use and waste of economic surplus in multiple areas of the Sri Lankan economy, both private and public sectors. Nonetheless, they tend to believe that the liberalisation of the economy through the market mechanism would sooner or later wipe away those imperfections and malpractices. The constant and continuous fiscal deficit and the deficit in the current account of the balance of payments (the so-called twin deficit) are in fact not the causes but the symptoms of the absence of capitalist development. The fiscal deficit and the deficit in the current account of the balance of payments demonstrates the presence of multiple deficits in many areas of the economy. Hence, the neoclassical explanation is based on circular reasoning. On the contrary, radical political economy attempts to get underneath the tempestuous surface of capitalism to identify the central tendencies and currents of the actual system.

The logic of capitalist development

Up to now, the economic performance has been assessed in terms of GDP, its rates of growth, and the level of per capita income. I argue that these conventional measures in themselves are not adequate to measure the success or failure of the process of capitalist development. Joseph Stiglitz (2019) has also argued on different grounds that these no longer serve as a key to measure economic performance or make predictions. He writes: “The standard measure of economic performance is gross domestic product (GDP), which is the sum of the value of goods and services produced within a country over a given period. GDP was humming along nicely, rising year after year, until the 2008 global financial crisis hit. The global financial crisis was the ultimate illustration of the deficiencies in commonly used metrics. None of those metrics gave policymakers or markets adequate warning that something was amiss. Though a few astute economists had sounded the alarm, the standard measures seemed to suggest everything was fine”.

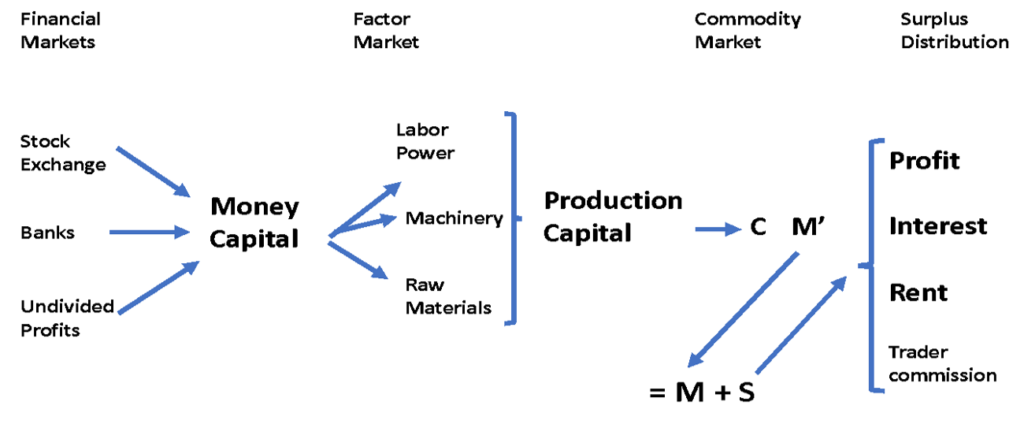

To measure if a country in the Global South is on the path of capitalist development or not, I would propose to deploy the categories and laws of capital accumulation as articulated by Marx in his three-volume magnum opus. The valorisation of capital is an inherent logic and the necessity for capitalism to exist. The valorisation of capital is a result of a continuous process of capital accumulation in which capital metamorphoses through varying phases briefly shown by the formula, ‘M → C → M’.

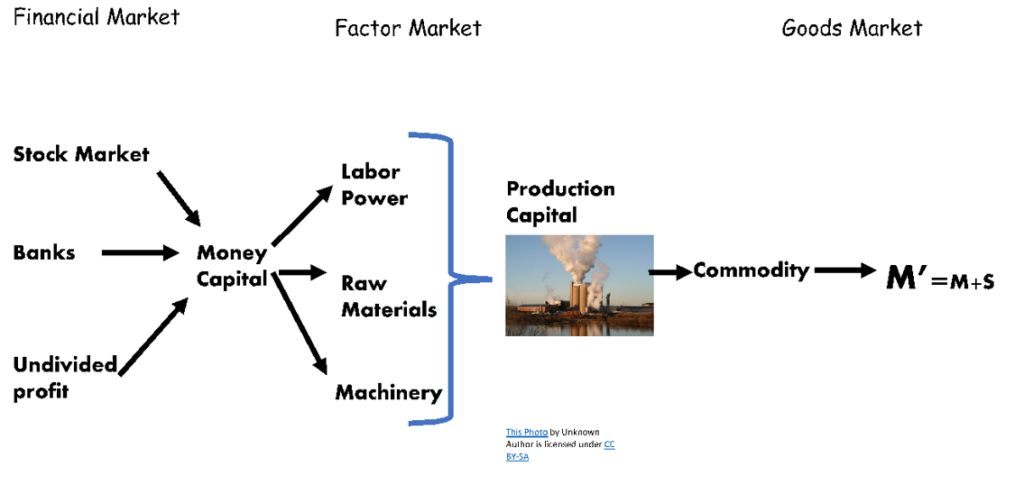

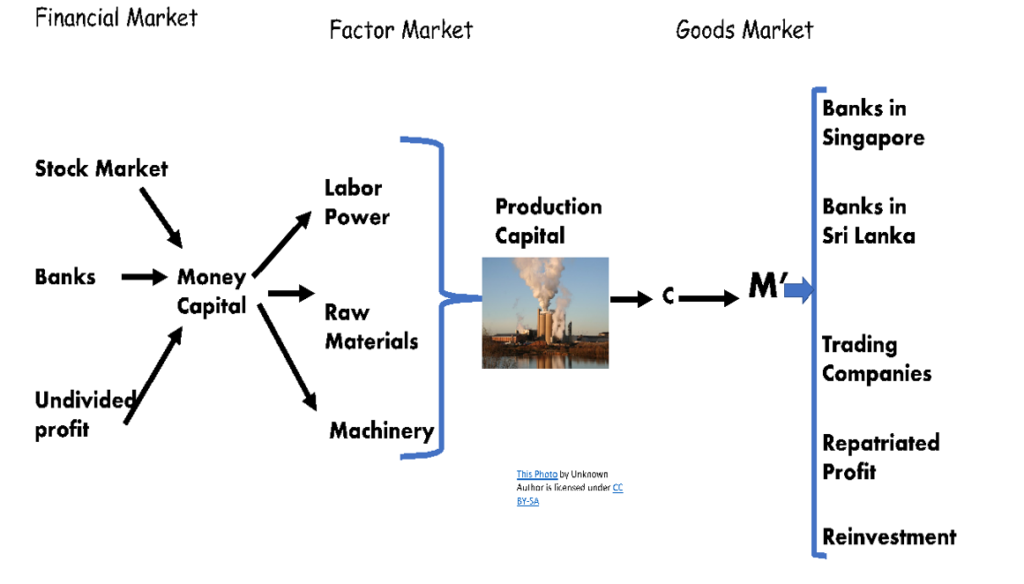

Figure 7 prepared by me on the basis of Marx’s argument in Capital Vol. 1 represents an expanded circuit of capital including the production process, interrupting the circulation process of capital. Here, M stands for money and C for commodities.

Figure 7: The circuit of capital

The process begins with the capitalist raising money capital in the financial market and converting that money capital into commodity capital in the labour market and the capital equipment market. Then, all these factors of production, namely labour power, raw materials and machinery, and other instruments, are extracted to the subterranean sites of production (factory) safe from prying eyes. The real accretion of value or the generation of surplus value happens in this “no entry territory” in which capital takes the form of production capital. The end result is a load of qualitatively different commodities, the market value of which when converted once again to money (M’) is greater than the amount of money (M) initially invested. M’ includes not only the amount of money initially invested, but also surplus value (S) generated in the production process. Thus, M’ = M + S. However, this should be realised at the market. The cycle will go on without interruption if the total value including surplus value is realised. If part of the surplus value is invested to generate more surplus value, we get an expanded cycle.

This process and its subsequent outcomes were vividly portrayed by Marx and Engels in the following words:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and, thereby the relations of production and with them the whole relations of society … Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are always swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned. (n.d.: 30-1)

As Mandel (1976) noted, “[u]nder capitalism, economic growth … appears in the form of accumulation of capital … The basic drive of the capitalist mode of production is the drive to accumulate capital” (60) The transfer of capital between the capitalists in different sectors is predicated by the relative rates of profit.

Once again Marx (1976) wrote:

Accumulate, accumulate! That is Moses and the prophets! Industry furnishes the material which saving accumulates. Therefore save, save, i.e. reconvert the greatest possible portion of surplus-value or surplus product into capital! accumulation for the sake of accumulation, production for the sake of production: this was the formula in which classical economics expressed the historical mission of the bourgeoisie in the period of its domination. (742)

The individual capitalist is invariably forced to expand his enterprise in depth and in width, with the result that productive forces of the economy have a tendency to continuous and constant increase. This is for two interrelated reasons. First, capital seeks to resolve the contradiction between capital and labour by making labour less significant and more subsumed within the process of production. Secondly, in a context of “many capitals”, real competition among capitalist enterprises leads individual enterprises incessantly to overtake its rivals to capture a larger share of the market. A need for continuous and constant increase in forces of production is thus embedded into the dynamic of capital accumulation.

How would it be reflected in the real economy? What are the metrics that can be deployed to denote capitalist development? Three main inter-related features may be specified.

1. From the production of absolute surplus value to that of relative surplus value:

In terms of the mode of surplus generation, Marx identifies two distinct logical phases of capitalist development. In the first phase, the increase of the rate of surplus value (S/V) depends on the total number of hours a worker is employed. Assuming the number of hours a worker needs to work to make sure that he and his family stay alive is constant, the capitalist can appropriate and expropriate more surplus value through increasing his daily working hours. This is termed ‘absolute surplus value’. Nonetheless, there are limits to this option, especially because the labour power is not an ordinary commodity since the owner of labour power (worker) tends to resist and demand. Hence, capital must persistently look for ways in which more surplus can be generated. This is done by improving the productivity of labour by improving the instruments of labour used in the production process. This is called ‘relative surplus value’ (Marx 1976: 432).

2. From formal subsumption of labour to real subsumption of labour:

In the initial phase of capitalist development, labour in the production process was subsumed and controlled by orders and supervision either by the owner or a supervisor handpicked by him. However, with the deployment of Taylorism and Fordism and the introduction of the conveyor belt system, labour is subsumed by the very operation of the machine and its speed. Now, subsumption of labour is embodied into the production structure. This is vividly depicted in the films of Charlie Chaplin.

3. From manufacture to machinofacture:

“In manufacture the transformation of the mode of production takes labour-power as its starting point. In [machinofacture] the instruments of labour are the starting point” (Marx 1976: 492). The new inventions and innovations shortening the pay-off period have made the machines the dominant player in machine production. Today computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) have revolutionised the entire mode of production.

All these three interrelated processes change the composition of capital in the course of the process of accumulation. Since the notion of the composition of capital is crucial to our examination of capitalist development in Sri Lanka, it is pertinent to clarify the concept.

The composition of capital may be defined in two ways, namely, a) value composition of capital; and b) the technical composition of capital. The value composition of capital refers to how the total capital is divided into the value of constant capital (C) that includes raw materials and plant and machinery, and the value of variable capital (V) that is spent on labour power as wages. The technical composition of capital shows how plant and machinery, raw materials and labour are integrated in the production function.

Through these notions, Marx developed a distinct idea called ‘organic composition of capital’. He states: “There is a close correlation between the two. To express this, I call the value composition of capital, in so far as it is determined by its technical composition and mirrors the changes in the latter, the organic composition of capital” (Marx 1976: 762). The organic composition of capital C/V increases with varying phases of capitalist development making the generation of relative surplus value and machinofacture the dominant mode of production.

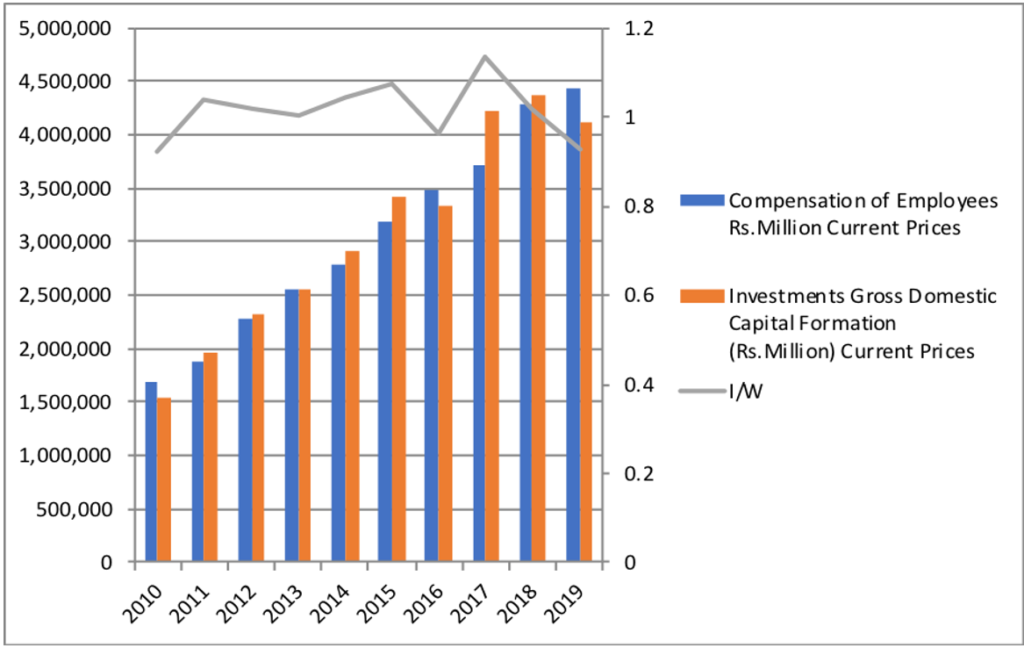

I submit that the organic composition of capital and its changes should be treated as the primary metric of capitalist development in Sri Lanka. Marx (1976) wrote that “the most important factor in this investigation is the composition of capital, and the changes it undergoes in the course of the process of accumulation” (762). Nonetheless, it is quite difficult to develop a reasonably accurate measure of these based on existing Sri Lankan official data. The measure used in Figure 8 is calculated taking the nearest possible variables in official statistics. Gross domestic fixed capital formation was taken as a proxy for C – constant capital, and compensation of employees as a proxy for V – variable capital. Hence, I/W is a proxy for C/V, the organic composition of capital.

Figure 8: Sri Lanka: The organic composition of capital, 2010-19

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka and Reports of the Commissioner of Labour (various)

If we consider the 1960-77 period, Sri Lanka had many state-owned corporations with higher organic composition of capital (OCC), although it was not reflected in the country-wide average OCC. Higher OCC signifies development of productive forces that in turn denotes capitalist development. As Bensaïd (2009) has pointed out, “the concept of productive forces … raises a problem that is common to most of Marx’s basic concepts: their descriptive enumeration varies with the level of determination of the concept” (49).

Figure 8 shows that, even 30 years after the introduction of neoliberal economic policies, there has been no significant change in the OCC indicating a low level of economic development and truncated process of capital accumulation. Many industries that emerged following the introduction of the outward-oriented economic strategy in 1978 were basically light industries. This in itself is not a major issue. What is, however, important is that the country has failed to move to the next phase of capital accumulation, resulting in increased productive forces and changed industrial structure.

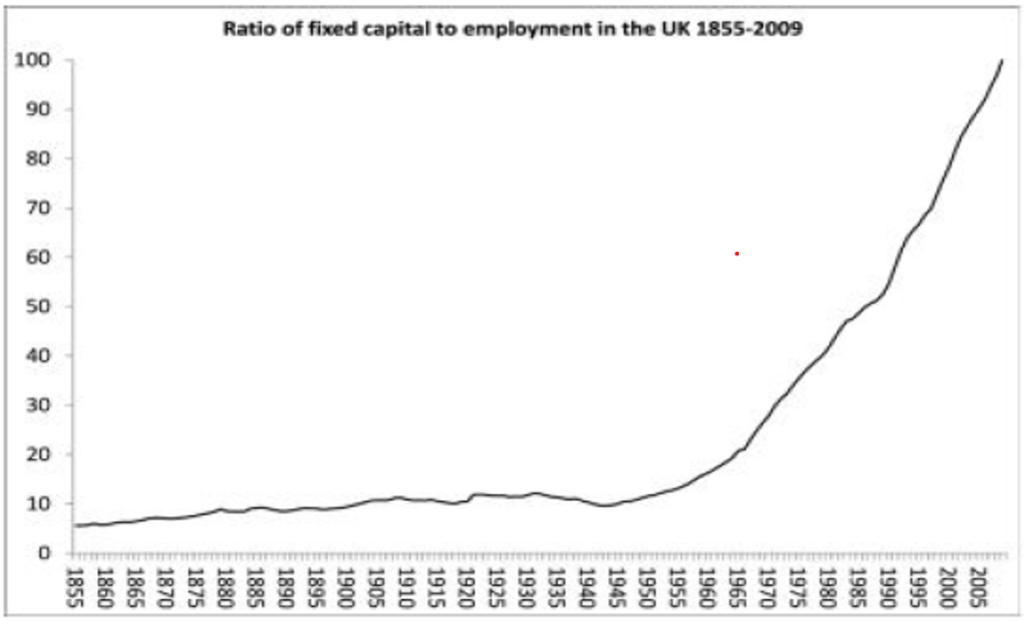

In order to get an idea of how, and to what extent, the OCC is important in deciphering the level of capital accumulation and the increase of productive forces, Figure 8 may be compared with Figure 9 that shows the behaviour of OCC in the phase of capitalist growth in the post-World War 2 period in the UK.

Figure 9: Organic composition of capital in the UK, 1855-2009

Source: Michael Roberts (2018: 33)

LMD has provided a list of the principal exporters of Sri Lanka with their respective scores of performances (see Figure 10). Out of 20, only two are engaged in real manufacturing production. Many companies are engaged in the light production industries and IT services. The organic composition of capital in those enterprises is relatively low.

Figure 10: Ranking Sri Lankan exporters

Source: LMD, Brands Annual 2020, 12 May 2020

How do we explain why Sri Lanka has been trapped in a low level of capital accumulation signifying an underdevelopment of productive forces? The question may not be resolved by limiting the analysis to the sphere of productive forces. It is imperative to go beyond this and to bring in the relations of production into the analysis. The correspondence between the productive forces and the relations of production has been subjected to intense debate in Marxist discourse as it is conceived as an element that accounts for the succession of the modes of production. The debate invariably invokes the oft-quoted passage from the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production … At a certain stage of development, the material forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production … with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution … No social order is ever destroyed before all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed and new superior relations of production never replace old ones before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the framework of the old society. Mankind thus inevitably sets itself only such tasks as it is able to solve, since closer examination will always show that the problem arises only when the material conditions for its solution are already present or at least in the course of formation. (Marx 1975: 425-6)

The above quotation may give room for multiple interpretations over the nature of the relationship between the productive forces and the relations of production since it refers to a contradiction between the two. What is dominant in the ensemble? Since the purpose of using these two concepts here is different, we may easily bracket this important and interesting debate. Nonetheless, the discussion begins with the conclusion that there is a correspondence between the two but without one dominating the other. The two are interdependent, and which element of the ensemble would be dominant depends on the concrete context. The productive forces are conceived by Marx to include the means of production and labour power. Hence, the deployment of new instruments of labour and the skill development and the novel experience of labour advance the productive forces. The relations of production entail how different strata of society are linked and related to the production process. Some may relate as owners, and some as non-owners or part-owners. This is historically determined.

My thesis here is that the truncated development of productive forces in Sri Lanka may be attributed to the nature of the relations of production that are historically determined by the colonial economic, social, and administrative structure. With the advent of the plantation system in the mid-1800s, the real appropriation of surplus was concentrated not at the point of production, but at the point of trade. As S. B. D. de Silva (1982) has shown, the dominance of agency houses in the management and trade of tea plantations became a hindrance to further development of productive forces. These colonial relations of production and their continuation with no noticeable change have now turned into fetters hindering further development of productive forces. The relations of production that were structured during the colonial period had not undergone a major transformation even after the establishment of local administration. The continuous dominance of merchant capital has made it possible to appropriate a major portion of the surplus through the control of circulation processes.

Although a new development dynamic was injected into the economy in 1977, it has operated within the given relations of production or without taking steps to transform it so that the dominant actors of the relations of production have become the main beneficiaries of the measures introduced since 1977.

The distribution of surplus among different groups of the dominant class depends on the power structure of the society. In the Sri Lankan politico-economic sphere, merchant and finance capital appear to be hegemonic in taking main economic decisions as well as enactment of laws relating to economic issues. This is reflected in the behaviour of profit rates among different capital groups. There has been a bias towards merchant and finance sectors in surplus distribution. As a result, new investment naturally seeks high profit areas that include education, health, banking, insurance, trade, and real estate.

Figure 11: Circuit of capital in BOI industries of Sri Lanka

Figure 11 above gives a stylised picture of the operation of foreign investments in industries coming under the Board of Investment (BOI).[4] This modified circuit of capital shows that a significant, if not the largest portion of surplus, is not handled by the local segment of companies, but by outside players such as foreign banks and trading multinationals that control global supply chains. What we have inherited from the colonial economic structure has been strengthened in the post-1977 period by integration into neoliberal globalisation. And this is by no means confined to Sri Lanka; it is a world-wide phenomenon. In this context, even if the GDP shows growth, it does not necessarily mean an advancement of productive forces and development.

After 45 years of the neoliberal regime, cracks have begun to appear in the very edifice of bourgeois rule. People tend to think that regime changes produce no positive results, and are thus, of no use. Ruptures have emerged in every sphere although in varying degrees and temporalities. The epidemiological crisis has shown clearly that the present system calls for a systemic transformation. When it made further advancement of productive forces within the given relations of production not possible, the system would turn into regressive measures. All over the world, we have seen that ruling classes seek to resolve the crisis by reinvigorating archaic modes of production.[5]

The best example for this is the response of Brandix, one of the companies with a high score of export performance (see Figure 10), to the epidemiological crisis. It is clear that Brandix had not paid adequate attention to taking precautionary measures to protect its workers from infection. The Joint Apparel Association Forum (JAAF) had officially informed the Labour Minister that Brandix earnings in later months had not fallen much compared to corresponding months in 2019. According to them, Brandix earned 382.4 million USD in June 2020 compared to 481.3 million USD in June 2019, and 441.9 million USD in July 2020 compared to 452 million USD in July 2019. All of this was achieved through the high level of exploitation of half the workforce they employed in the pre-COVID19 period, adding to their profits the wages and saved Employees Provident Fund/Employees Trust Fund contributions. This shows that a company of the 21st century is still using the early 19th century mode of surplus generation, namely production of absolute surplus value.

The behaviour of the Brandix company towards its workers reminds us of the factory situation in the early phase of capitalism. The medical centre at Brandix had given only pain relief medications to a majority of employees who had complained of fever, colds, and coughs. Dr Sudath Samaraweera is on record stating that: “When analysing the details of the factory workers, we noticed that there had been respiratory diseases in some factory workers since 20 September, even though the female factory worker who first tested positive, had developed symptoms on 28 September” (Fernandopulle 2020) More than a hundred years ago, Marx (1976) wrote: “Capital takes no account of the health and the length of the life of the worker unless society forces it to do so” (381) When trade unions and worker activists protest over hygiene conditions, Capital would respond like Shylock: “my deeds upon my head! I crave the law, the penalty and forfeit of my bond.”[6]

Brandix is just a tip of the iceberg epitomising the economic facet of the organic crisis. Having referred to Hall’s definition of organic crisis quoted above, it is “what happens to hegemony when capitalists as a class fail to maintain it”. It has been widely reported that more than 700 people in the country had died by suicide just in the first three months of 2020. Non-communicable diseases that are directly or indirectly related to capital accumulation in agriculture have been increasing.

With slight changes on the right-hand end of it, Figure 7 or 11 may be rearranged to depict the competition between ‘many capitals’, namely, production capital, finance and banking capital, trading, or merchant capital, etc. (Figure 12). This was an aspect S. B. D. de Silva (1982) dealt with in his book The Political Economy of Underdevelopment. The development of capitalism depends not only on the magnitude of the surplus created but also how these surpluses are used at the beginning of the next cycle.

This issue takes us to a real competition between capitalists concentrated in different sectors. As Shaikh (2016) observes “the local Chamber of Commerce [is] their house of worship” (261). The movement of surplus is determined by the inter-sectoral relative profit rates. Nonetheless, the behaviour of the inter-sectoral rates of profit are invariably manipulated by hegemonic segments of the capitalist class in their favour. History shows us that, in a situation in which the production capital was able to become the dominant power subordinating the power and influence of banking, finance, and trading capitals, the possibility of capitalist development was remarkable. The economic history of many developed countries shows that, at some stage of the development process, production capital was able to become the hegemonic power of capital. The state in those respective countries played an active role in the process (Chang 2008). Since the pressure and influence that can be exerted on the process of decision-making by the Ceylon Chambers of Commerce (CCC) is high, the composition of its director board is of great importance. A majority of the members of the director board of the CCC are representatives, not from the production sector, but from other service-related sectors.

Figure 12: Circuit of capital surplus appropriation

Conclusion

The Sri Lankan economy is trapped in the contradiction between the productive forces and the relations of production. Commodification of all products and the marketisation of all activities, as neoliberal economists propose, will not be a solution to this impasse. As we have seen above, the opening of the capital market and the market-determined transfer of capital invariably act in support of non-productive sectors and against productive sectors. The productive/unproductive labour distinction drawn here does not imply that unproductive labour is non-useful labour. Rather, non-productive labour is essential for the operation of the system.

Supporters of neoliberal strategies may argue that this problematic transfer of capital would be resolved in the long run through the process of equalisation of profit. However, it is not the strength of the market that determines the inter-sectoral movement of capital, but the relative strength of the different groupings of the capitalist classes. The organic crisis of neoliberalism does not necessarily lead to an end of the system. It moves us from a time of necessity to a time of possibilities. The vector of possibilities that has been created by the present impasse will leave future developments open. Therefore, how this organic crisis could be resolved is not an issue of economics or history, but an issue of politics and the constellation of forces in the domain of politics.

Let me conclude by revisiting what Gramsci (1971) has noted: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

Sumanasiri Liyanage is a political economist who retired as associate professor in the Department of Economics and Statistics at the University of Peradeniya; and co-convenor of the Marx School in Sri Lanka.

Image credit: Diego Rivera (1935) “Mexico Today and Tomorrow” detail featuring Karl Marx, History of Mexico murals, fresco, Palacio Nacional, Mexico City; photographed by Wolfgang Sauber

References

Bensaïd, Daniel. (2009). Marx for our Times: Adventures and Misadventures of a Critique. London: Verso.

Chang, Ha-Joon. (2008). Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Colombage, Sirimevan. (2024). Reforming Macroeconomic Policies for Stability and Growth: Sri Lanka’s Road to Economic Recovery. Colombo: Gamini Corea Foundation.

De Silva, S. B. D. (1982). The Political Economy of Underdevelopment. London: Routledge.

Engels, Friedrich. (1969). “Introduction”, The Class Struggles in France 1848-1850. In Karl Marx and Frederick Engels Selected Works. Vol. 1. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Fernandopulle, Sheain. (2020). “Woman factory workers not origin of existing cluster.” Daily Mirror (7 October): https://www.dailymirror.lk/print/breaking_news/Woman-factory-worker-not-origin-of-existing-cluster/108-197348

Gramsci, Antonio. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks, edited and translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. New York: International Publishers.

Hall, Stuart. (1988). The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left. London: Verso.

IMF. (2020). “Gross Domestic Product: An Economy’s All.” IMF Finance & Development Magazine (24 February). Available at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/gdp.htm

Keynes, John Maynard. (2013). “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.” In Collected Writings of J M Keynes, Vol. 7. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kuhn, Thomas. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levenson, Zachary. (2020). “An Organic Crisis Is Upon Us – When Gramsci Goes Viral.” Spectre (20 April). Available at https://spectrejournal.com/an-organic-crisis-is-upon-us/

Mandel, Ernest. (1976). “Introduction.” In Karl Marx, Capital Volume 1. London: Penguin Books.

Mandel, Ernest. (1977). The Second Slump: A Marxist Analysis of Recession in the Seventies. London: Verso.

Mandel, Ernest. (1995). Long Waves of Capitalist Development: A Marxist Interpretation. 2nd Edition. London: Verso.

Marx, Karl. (1975). “Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy.” In Early Writings. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. (1976). Capital Volume 1. London: Penguin.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. (n.d.). The Communist Manifesto. Toronto: Vanguard Publication.

Meszaros, Istvan. (2010). Beyond Capital: Toward a Theory of Transition. New York: Monthly Review Press.

OECD. “GDP.” In Glossary of Statistical Terms. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264055087-en

Patnaik, Prabhat. (2022). “Reflections on the Sri Lankan Economic Crisis.” Peoples Democracy (1 May). Available at https://peoplesdemocracy.in/2022/0501_pd/reflections-sri-lankan-economic-crisis

Roberts, Michael. (2018). Marx 200: A review of Marx’s Economics 200 years after his Birth. Raleigh, NC: Lulu Press.

Shaikh, Anwar. (1978). “An Introduction to the History of Crisis Theories.” In URPE (Ed.) US Capitalism in Crisis. New York: Union for Radical Political Economics.

Shaikh, Anwar. (2011). “The First Great Depression of the 21st Century.” In Leo Panitch, Gregory Albo, and Vivek Chibber (Eds.). Socialist Register 2011: The Crisis This Time (44-63). London: The Merlin Press.

Shaikh, Anwar. (2016). Capitalism, Conflict and Crises. New York: Oxford University Press.

Shaikh, Anwar M. and E. Ahmet Tonak. (1994). Measuring the Wealth of Nations: The Political Economy of National Accounts. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stiglitz, Joseph. (2019). “It is time to retire metrics like GDP. They don’t measure everything that matters.” The Guardian (24 November): https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/nov/24/metrics-gdp-economic-performance-social-progress.

Weeks, John E. (2014). Economics of the 1%: How Mainstream Economics Serves the Rich, Obscures Reality and Distorts Policy. London: Anthem Press.

Wijewardena, W. A. (2020). “Rebuilding of the economy in post-COVID-19 era: Acquisition of technology a must”, Daily FT (12 October): http://www.ft.lk/columns/Rebuilding-of-the-economy-in-post-COVID-19-era-Acquisition-of-technology-a-must/4-707308.

Williams, Raymond. (1977). Marxism and Literature. New York: Oxford University Press.

[1] Editors’ note: This is the text of the speech delivered by the author at the Professor H. A. de S. Gunasekera Memorial Oration 2025 held on 10 January at the University of Peradeniya. It has been lightly edited for publication.

[2] Acknowledgements: I wish to thank Dr. Piyasiri Wickramasekara, Dr. Anuruddha Kankanamge, and Dr. Ranil Abayasekara for their valuable comments; Ms. Chamari Wijewardena for copy-editing; and Ms. Emesha Perera for preparing graphs.

[3] Editors’ note: “Accumulation” in the original.

[4] I thank Dr Vagisha Gunasekera for this information that is based on her research on the BOI sector.

[5] This aspect is discussed at length in my paper entitled “The Reactivation of Archaic Mode of Production” presented at the Marx 200 Centenary Seminar at the South Asian University, Delhi. 2018.

[6] Shakespeare, William. (1600). Merchant of Venice, Act 4, Scene 1.

You May Also Like…

Obeyesekere the Dreamer: Visionary Journeys in Anthropology

Anushka Kahandagamage

I remember vividly one pattern in my youthful dreams repeated time and again, without too much variation, that of...

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...