The Im/Possibility of Justice in the Current Global Order

Kiran Kaur Grewal

It is such an honour to deliver the 2025 Rajani Thiranagama Memorial Lecture.[1] Having worked in human rights for over 20 years, and in Sri Lanka since 2012, the name Rajani Thiranagama is a symbol of courage and integrity. And these annual lectures in her name provide an important opportunity for us to reflect on the ongoing quest for a fairer, less violent, more just world.

This year it is easy to feel that justice is an elusive fantasy. Whether we look locally at the mass graves being uncovered around the country, the harm done by the debt crisis to ordinary people’s standard of living, or we look internationally where the entire UN and post-World War 2 justice system is being destroyed to allow for a genocide to take place in Palestine—how do we even begin to conceive of justice?

I do not want to call this a moment of ‘crisis’; even though it is definitely, in the words of the Italian anarchist Antonio Gramsci, ‘a time of monsters’. Rather I see this as the inevitable end of a particular era. Over 500 years of Western imperialism, capitalism and human-centric exploitation of the planet has led us here. And we are seeing this epoch in its final, rawest, most desperate form as it tries to cling onto power. Make no mistake, the old order is dying.

At the same time a new order is yet to be born. We need to find the strength and imagination to work on building whatever comes next. This is not about replacing one global hegemon with another. I do not believe that the rise of India, China, Russia or Brazil will offer a better alternative. The divide is not between the West and the Rest but—as the Occupy Movement clarified—between the 1% and 99%. It is up to us, the people, the world’s majority, to work out new ways to live. In this talk, while I offer no solutions—this is a collective project in the making—I offer some tentative ideas about what we might need to do.

None of us is free until all of us are free!

First we need to return to the idea that none of us is free until all of us are free. Whether it is the endless ravaging of the mineral rich Democratic Republic of Congo so we can have the latest smartphone, laptop or electric car, the brutal exploitation of Sudan to extract gold, or the destruction of Gaza to pave the way for luxury beach resorts, we need to see our struggles as interconnected.

In the immediate aftermath of World War 2, we saw the birth of an amazing Third World movement as newly decolonised and still decolonising states came together to fight the old imperial world order. And they had a number of successes. As a human rights scholar and practitioner it makes me very frustrated when people claim that human rights are a Western thing. In fact many of the important developments within the international human rights system came as a result of the hard work of countries and people in the Global South. To give you a few examples:

1. The Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, not only identified the problem of racism but also specifically named and condemned the practice of apartheid and zionism, two institutions that were long supported by the West. It took many decades of struggle for apartheid South Africa to finally be dismantled and the US and UK were the last to support it. It was resolutions, boycotts and sanctions led by many parts of the Global South and supported by ordinary people around the world that brought apartheid to an end. We are seeing the same struggle now with Palestine.

2. International Humanitarian Law—the ‘laws of war’—was historically extremely limited. Even the Geneva Conventions drafted after World War 2 focused mainly on the rights of soldiers and states. It was only as a result of a decade-long sustained campaign of reform led by the Third World/Non Aligned movement that the Geneva Conventions were enhanced by Additional Protocols I and II in 1977 that both recognised the legitimacy of resistance to colonisation, occupation, and racial domination, and provided extended protections to ordinary civilians caught up in wars.

3. It was only through the constant lobbying and pressure of the Global South that the issues of development, cultural and indigenous rights even made it onto the global agenda. It is thanks to these nations—not the West—that we have such things as the Declaration on the Right to Development and the UN Convention on the Rights of Indigenous People.

Even now, whatever Western leaders may say, human rights and international law are not just about what the West wants—this is why there is a near global consensus within the international legal and human rights community condemning Israel and the US. It is why the only way to prevent international prosecutions has been for the US to actively try to sanction and dismantle the UN and International Criminal Court, and UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer has had to destroy his own career and credibility as an international human rights lawyer to avoid condemning Israel. But again, if we look back, this is not a new or sudden break the West has made with human rights. We have to stop accepting the dominant story, told by both advocates and critics, which overstates the West’s role in championing human rights. This story in fact only really took hold in the 1990s.

It is accompanied by the fragmentation of the Third World movement in the late 1980s and, with the fall of the Soviet Union, the rise of Western hegemonic power. The apparent ‘victory’ of Western neo-liberal democracy has been hugely destructive of our sense of solidarity. I have witnessed this at a micro level when I compare the sense of interconnectedness of struggles among older generations and the sense of isolation among younger ones. Last year, when I brought a Palestinian human rights lecturer and her student to Sri Lanka it was notable to see how older Sri Lankans were so aware of the Palestinian struggle while the young ones knew little about it, just as the Palestinians knew nothing of Sri Lanka or even movements closer to home like the Kurdish freedom struggle. This is an important loss because there is much to be gained through sharing our experiences and our strategies, identifying sites of common struggle and building alliances where we can.

I think we are seeing an important shift happening again. Certainly in the pro-Palestine activism I have been participating in, many echo the sentiment that this is not just about Palestine but through solidarity with Palestine we will all be set free. We have also seen some leadership on the global stage—through the actions of South Africa in initiating a case against Israel in the International Court of Justice, and Colombia trying to gain support for a ‘Uniting for Peace’ resolution in the UN General Assembly that would allow for the bypassing of the UN Security Council where the US keeps abusing its veto to prevent action to stop Israel’s genocide. But it is also importantly happening beyond the control of nation states—with initiatives like the Global Flotilla and the Boycott Divest and Sanctions movement. In the process, these movements are not just challenging Israel’s actions. They are also challenging the ability of powerful states to call the shots, and activating populations around the world, separate from what their governments are doing purportedly in their name.

Now is the time to build on that momentum. For the first time the people of the West are seeing the hypocrisy and corruption of their own governments clearly. Especially as Western governments are now doing to their own populations what they have long done to others (something I will say more about in a moment!). The West’s mask of legitimacy has fallen. We can’t let it be reclaimed. We need to resist the temptation to take short term gains by appealing to hegemonic powers to support our struggle in isolation. We can’t let them rehabilitate their images or regain control through the instrumentalisation of our voices and suffering. While I was happy to see the UK government sanction Sri Lankan war criminals and to see the Canadian government recognise the Tamil genocide, we need to keep reminding them that this does not absolve them of their responsibility to stop supporting an ongoing genocide in Palestine. I have been working closely with a Bosnian feminist lawyer who is explicit in condemning those who attempt to use their support for Bosnia as a cover for their current actions in relation to Palestine.

So too, my concern is not just for Palestine and Palestinian people, just as the condemnation of the Holocaust was not just about protecting Jewish people. Rather, it is about identifying, naming and dismantling the structures that allow for the dehumanisation of any group of people. In Europe, right now we are seeing the parallel processes used against Jewish people that led up to the Holocaust now being used against Muslims. It is disgusting and shows we in fact learnt nothing at all from the horrors of the past.

Meanwhile human rights has become a tool to be used to claim something rather than a responsibility that we all have to each other. This is something I feel strongly about as a diasporan Sikh Punjabi. While we have been quick to link our experiences in 1984[2] to the suffering of Tamils in 1983, I have also urged my community to acknowledge and speak out about the suffering Sikhs caused as part of the Indian Peace Keeping Force here in Sri Lanka between 1987 and 1990. If we can speak of our victimhood we should be equally able to speak out and condemn our involvement as perpetrators.

Meanwhile, living in the West I have seen identity politics used to create hierarchies of suffering and a sense of competition between different marginalised groups: migrants, indigenous communities, sexual minorities, etc. This is a form of neo-liberal thinking that makes everything a zero sum game—“I can only win if someone else loses”. It also fails to recognise the shared logic underpinning many of our oppressions. It keeps us fighting against each other while the powerful centre remains untouched. For this reason some of us are rejecting identity politics in favour of a politics based on the world we would like to see rather than based on who we are.

To put it very crudely, if we want others to care about our struggles, we have to care about theirs. This is how solidarity is built.

Away from the individual and the spectacular towards the collective and the everyday

What else do we need to build solidarity? In one of the many discussions we had in 2024 about how to engage in pro-Palestine activism, we spoke about movement-building. A young organiser was telling us about the difficulties in finding good leaders when one of the students piped up, “You know, I don’t want to be a leader. I just want to be the little guy who shows up.”

Those words have stuck with me. It is easy to lament the leaders we have. But we have to remember that we are the ones who put them there. They lead because the rest of us allow them to. Because we keep accepting that leadership looks like that—self-interested, power-hungry, self-promoting, arrogant. Because we don’t place value on humility, compassion, self-sacrifice, and care as leadership qualities.

And maybe it is about time we see that change doesn’t come from the top leading the way. After all, when they benefit from the status quo, why would we think they have the awareness, imagination and interest in changing things? This means that, rather than waiting for the revolution and leader to show us the way, we may need to accept that it is on us to do the hard work of creating the type of society and world we want to live in. This is not spectacular work, it is the work of the everyday. And it is not the work of one inspired, charismatic leader but the work of a movement.

Hope as a form of radical resistance

When we look at the scale of the injustices, it is easy to feel overwhelmed. But this is also part of the strategy. In the words of American anthropologist activist David Graeber, hopelessness is not accidental. There is an immense infrastructure and investment in making us feel that there is no alternative, that any action we take is futile, forcing us to conform, give up, feel powerless. With this in mind, continuing to hope for change is actually an act of radical resistance! I will give you an example.

From October 2023 hundreds of thousands of people around the world have taken to the streets to protest the massacre of Palestinian people. Week after week, month after month in London my daughter and I, with a group of friends, came out to walk through the city in rain, wind, cold, and heat. And we were told it was pointless. After all, a million people had marched against the Iraq War, and that went ahead anyway, didn’t it? As the months turned into years, we have felt hopeless. When I was in London in July this year, we took our pots and pans to Downing Street and beat them for hours, day after day, as a protest against the forced starvation of Gaza. Many of us cried. We all agreed that we did this out of sheer desperation that this horrific crime was being supported by our government and we wanted to note that this was not in our name. It felt like helpless rage.

We haven’t stopped the genocide. Our elected leaders have continued to act against our wishes. BUT they have begun to find it harder and harder to ignore us. While they relied on us getting exhausted and giving up, we haven’t. The movement for Palestine has grown. Earlier, many people did not really know the situation. Now public opinion across the West—particularly among the young—has shifted completely. Israel is becoming a despised state. Our leaders know this, so they have moved from ignoring and ridiculing to now actively criminalising and trying to stop us. Did you know that around 2,000 people—including elderly people, people with disabilities, religious figures, war veterans, academics, writers, artists, and civil servants—have been arrested in the UK in the last 2 months for peacefully holding signs condemning genocide and expressing support for a protest group called Palestine Action? And that Palestine Action has been proscribed as a terrorist organisation, having never committed a single act of violence but simply blocking weapons companies? All the while, weapons companies continue to produce their lethal goods with full legitimacy.

As I said, this is a time of monsters. A time where those protesting a genocide are criminalised and those committing it are protected. But the fact that Western governments have had to destroy the civil rights and democratic systems that their populations have come to expect in order to allow for this has made them very fragile. It has galvanised resistance. For the first time ever in the UK, the Green Party—a hitherto marginal left-wing party—has more members than the Conservative Party and is polling higher than the Labour Party. Just as in Sri Lanka, the people sent a strong message to the traditional parties by transforming the National People’s Power (NPP) from a marginal party to a strong majority government, the people of the UK are finally refusing to accept the status quo. I am not naïve in thinking that a major transformation is imminent, but the seeds have been sown for something new, and now we have to cultivate them.

Building alternate communities

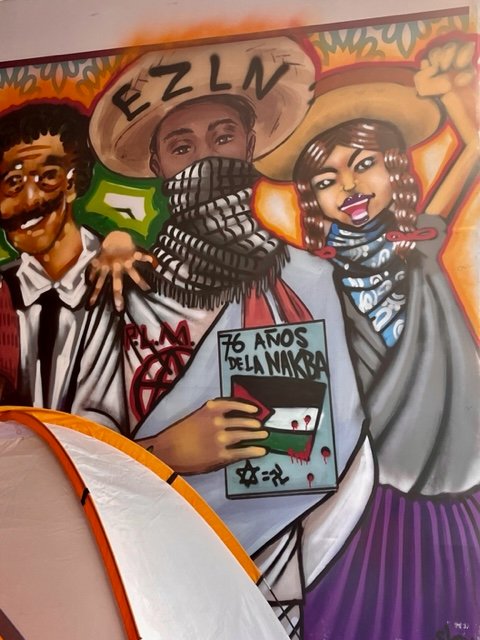

And this takes me to my last point. From January to April 2024, students at Goldsmiths College, London staged an occupation of the large Media Studies building on campus. Turning lecture theatres into dormitories, they hosted teach-ins, discussions, art shows, and community gatherings, all while protesting the university management’s refusal to name the genocide in Palestine and take active steps to cut ties with Israel. While I was sceptical at first about what the students hoped to achieve, many of us academics came to see their encampment as a welcome breath of fresh air and a reclaiming of the university for what it should be—not a neo-liberal degree factory, but a place of education where people showed curiosity and a desire to learn, where critical thinking was encouraged and space given to debate, discussion, and experimentation.

Moreover, it was cultivated as a space of acceptance and openness, where everyone was welcome (even the security guards!) and where new forms of community—the communities students wanted to see exist—were modelled. Each afternoon they held a community meeting to discuss how everyone felt in the space, to deal with disagreements, to confront any potential issues of sexism, racism or other forms of discrimination. They celebrated Jewish and Muslim rituals. They sang protest songs in Hindi, Italian, Spanish, Turkish, Arabic, and Japanese.

When the encampment finally came to an end, we all felt a profound sense of loss. But we also felt we had gained something. A sense of what we could be—as a community, and as a society.

I have had the good fortune to experience this here in Sri Lanka too. In a little ‘feminist house’ that a friend cultivated in Mullaitivu between 2016 and 2019. In a space a group of us created in Batticaloa from 2018 to 2020. At Gotagogama in Colombo in 2022. In the Batticaloa Justice March that continues to this day. And I know this has existed before too—I remember reading about Poorani Women’s Centre in Jaffna from the 1990s. I know there have been many more such examples.

These little spaces are not insignificant even if they remain small and temporary. They are all gestures towards what we can be, how we can live. Spaces of love and care, hope and solidarity that speak back to the asserted ‘reality’ and permanence of the current dominant order. It is in learning to see and value these spaces that some clues may be found for how we build the new order.

One of the most beautiful images I can think of for this comes from a book called Survival of the Fireflies by French philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman (2009). What if we build our resistance in the way of fireflies—not one large spectacular light but many tiny, flickering, fragile lights that together can light the dark night sky? Maybe that is how, in the impossibility of the current moment, a new form of justice can be built.

Kiran Kaur Grewal is a human rights lawyer and scholar who is currently Visiting Professor in Gender Studies at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

Image credits: Kiran Kaur Grewal (lead image – 2024, graffiti in Oaxaca, Mexico); Shutterstock (final image)

[1] Editors’ Note: The 2025 Rajani Thiranagama Memorial Lecture was delivered in Jaffna on 19 October 2025.

[2] The anti-Sikh violence in India that followed the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in which many thousands of Sikhs were killed, their homes and properties burned, and their communities displaced.

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...