Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984, several weeks after I had returned to the United States after completing my PhD at SOAS. I approached him after a panel, introduced myself, and mentioned that I was planning to visit a friend at Princeton in the coming weeks. He generously invited me to have lunch with him at the Faculty Club at Princeton, where he quizzed me about my work. His interest gave me, an unknown and unemployed researcher, a boost in morale. The meeting turned out to be the beginning of a four-decade long connection.

For the next 16 years, until Gananath’s retirement from Princeton in 2000, my relationship with him was unremarkable. I had no institutional connection with him. Since I am a historian, we had no disciplinary connection, which meant I did not see him at anthropology conferences, though our paths occasionally crossed at the Annual Conference on South Asia in Madison or the annual conference of the Association for Asian Studies.

But of course, like for most scholars working on Sri Lanka in the humanities and social sciences in the late 20th century, his intellectual influence was always present. The 1988 book Buddhism Transformed, co-authored with Richard Gombrich, was especially influential, and much discussed and debated within my own intellectual circles. This was also the time when the ‘ethnic conflict’ came to dominate Sri Lanka scholarship, both directly and indirectly. Gananath’s interventions served as a moral beacon, and he took much criticism in nationalist circles as a result.

When Gananath retired from Princeton, I got to know him better, as he and Ranjini started spending time in Massachusetts, where I live, in order to visit family. There were relaxed meals with others interested in Sri Lanka who lived in the area, including Charlie Hallisey, Janet Gyatso, the late Stanley Tambiah, and Vijaya and Dineli Samaraweera.

But when Trump won the November 2016 election, Gananath declared that he would never return to the United States, and he kept to his word. Fortunately, from 2015 onwards I started to spend considerable time in Sri Lanka, so was able to keep up the friendship with Gananath and Ranjini, particularly with dinners at the Palmyrah, which had become Gananath’s favourite restaurant. Sadly, the pandemic put an end to these gatherings, though I was fortunate to be able to meet him and chat one last time in July 2024, at the house on Lauries Road.

My most substantive intellectual engagement with Gananath came towards the end of his long and astonishingly productive career, when he was working on the most historical of his books, The Doomed King: A Requiem for Sri Vikrama Rajasinha. This project marked a break from the work that made him a global giant among anthropologists. He declared that he did not care what anyone outside Sri Lanka thought of the book, as it was written for Sri Lankans, as an intervention in public culture, and that it would only be published locally.

The book is still “academic”, in the sense that it follows scholarly conventions and draws on his vast knowledge of Sri Lankan culture. But at its core it seeks to uncover a “real” Sri Lanka, the Sri Lanka that Gananath longed for, a Sri Lanka that had been mostly lost in the troubled post-colonial history of the island. His hope was that people would read the book and understand that there were strands of Sri Lankan culture that had been forgotten, but which were worth remembering, and which could be used to make a better society today.

This shift in the intended audience for his historical work on Kandy, undertaken after his retirement from Princeton, should not however distract from an important continuity—the ethical and moral base that informed his entire career, not only his academic work, but his life, including his interactions with his peers and juniors. This, along with his charm and intellectual power, is captured by the 2024 documentary film directed by Dimuthu Saman Wettasinghe, Gananath Obeyesekere: In Search of Buddhist Conscience, which is a brilliant tribute not only to his scholarship but to his person.

I feel very privileged to have known Gananath for four decades.

John D. Rogers is United States Director of the American Institute for Sri Lankan Studies; and author of Crime, Justice and Society in Colonial Sri Lanka (Curzon Press, London, 1987).

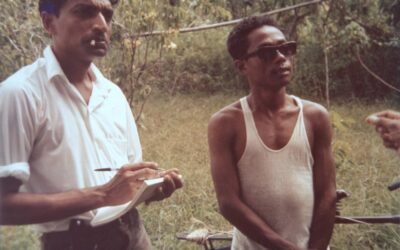

Photo credit: International Centre for Ethnic Studies (2015).

(L to R) Sarath Amunugama, Gananath Obeyesekere, John D. Rogers at a panel discussion on the life and work of Stanley J. Tambiah held on 30 November 2015 at the International Centre for Ethnic Studies, Colombo.

You May Also Like…

An Accidental Education with Gananath Obeyesekere

Mark P. Whitaker

I must begin with an embarrassing admission. Although Gananath Obeyesekere became my PhD thesis supervisor in...

Twenty Years of the PDVA: How has it worked for Women?

Chulani Kodikara

October 2025 marked 20 years since the Prevention of Domestic Violence Act (PDVA) was unanimously passed by...

Gananath: Two Stories and A Review

Victor C. de Munck

I was an undergraduate, and later a graduate, student of Gananath.[1] I have two stories I would like to recount. The...