Best Reads in 2024

Collective

A sinister thread of horror, known and unknown, real and imagined, has connected much of what I have read this year. First, The Saint of Bright Doors (2023) by Vajra Chandrasekera was an unexpected favourite. This wittily recounted fever dream of a novel was even more surprising, unruly, grimly hilarious, and subversive than its many well-deserved accolades have spoken to. Here, the horrors are exaggerated and grotesque but intensely familiar to those of us from the island resisting our fates and histories alongside the novel’s reluctant protagonist, Fetter.

Secondly, Mariana Enriquez is easily one of my favourite writers and each new translation of her work feels like an exquisite but diabolical haunted gift. A Sunny Place for Shady People (2024, translated by Megan McDowell) threads together twelve frightening and fantastical encounters with terror, both embodied and lurking in the ruins of the everyday. Lyrically formulated places and characters are inhabited by ghosts and visceral evils that torment the living, fictional and otherwise. The monstrous violence of empire, state, and capitalist extraction and exploitation that Chandrasekera and Enriquez point to is vividly lived in Sri Lanka, Argentina, and beyond.

Finally, Mosab Abu Toha, the Palestinian poet and founder of the Edward Said Public Library, the first English-language library in Gaza, charts, in poetry, the shattering violence of colonialism as the Israeli state’s mass atrocities continue with impunity into a fifteenth month. Forest of Noise (2024) is a devastating indictment of a world, directly complicit in the production and normalisation of the conditions of imperial violence, that has watched, permitted to happen, and refused to name a genocide. Written amid the endless horrors of the Israeli occupation and genocide, Abu Toha attempts to make sense of the extraordinary pain of living and remembering, the fight for survival amid ongoing Nakba, and wishes, heart-wrenchingly, for little dignities in life and death.

Vindhya Buthpitiya is an anthropologist working at the intersection of politics and visual culture, researching photography, resistance, ethno-nationalist conflict, and political violence in Sri Lanka.

My three “best reads” happen to be by a younger generation of Sri Lankan diasporic writers and editors. This generation, whether in or out of Sri Lanka, has been gaining traction on the global literary scene. They have inherited old memories but are able to tell stories with them in entirely new ways, drawing on cross national connections and larger frames of reference which make them all the more exciting.

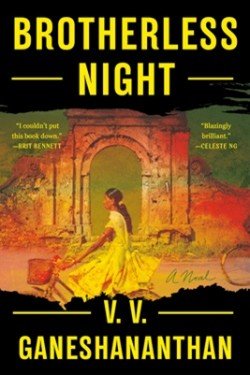

Brotherless Night (2023) by V. V. Ganeshananthan, Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens (2022) by Shankari Chandran, and the anthology Out of Sri Lanka (2023) edited by Shash Trevett, Seni Seneviratne and Vidyan Ravinthiran deal with Sri Lanka’s recent past, its war, its politics, and its diasporas. They bring us a range of characters and voices on surviving violence whether in war or domestic strife. Feisty and angry or compassionate and empathetic, they are often witty, and insistent on the just and humane. Both the novels have strong women as protagonists.

Brotherless Night, a bildungsroman, tells the story of Shashi, a young Tamil girl/woman who comes into her own through her wartime experiences. She loses her eponymous brothers to it, treats cadres and war victims as a doctor, and comes under the influence of Dr. Anjali (a homage to Rajini Thiranagama). At the centre of her story is her ambivalent relationship with K. The latter joins the LTTE, and, like its Thileepan, undertakes a death fast at which Shashi keeps vigil. I found this death fast scene, which marks the book’s most intense passage, quite brilliant. Ganeshananthan closely followed D.B.S. Jeyaraj’s account of the real event but, as with good historical fiction, introduces nuance and inner lines of thought in how and why Shashi finally lays claim publicly to K as “her man”, sitting as a “good” wife would beside her dying husband, and detesting the LTTE as a rival for appropriating his life and body for its cause.

Chai Time is an altogether lighter read thanks to its witty characters. Diaspora novels revel in the serendipity and tensions that arise from mixing. Maya, a Sri Lankan Tamil woman, runs an aged care home in the suburb of Sydney together with her daughter Anjali. Immediately, a multi-ethnic, multi-generational cast of characters becomes possible. Cultural missteps (often the source of laughter), racism, and memories of violence mingle, reminding the characters, and us, that original and new homelands can be similar. We also learn as much about Sri Lanka – for instance of a Bohra community in Jaffna (erased in the current narrative on both Tamil and Muslim minority politics) through Maya’s marriage to Zakhir, as we do of right-wing Australia’s obsession with Captain Cook. The novel needed a firmer edit, but I found most of its characters fun and enduring.

Out of Sri Lanka is a precious gift to those of us too urban and monolingual in our reading. Mining a wide range of poetry from all regions in Sri Lanka, its diasporas, and its three main languages, the anthology is a wonderful compendium of Sri Lankan literature. The translations are superb. I loved its introductions to the poets, both veteran and new, and its selection of a gamut of “Sri Lankan” experiences that speak, however, to wars, domestic violence, love, and grief elsewhere. Vitally, for me, the anthology expands the canon on Sri Lankan literature to show its breadth, depth, and craft.

Neloufer de Mel is Emeritus Professor of English, University of Colombo, and a former Chair of the Gratiaen Trust.

Three books that have shaped 2024 for me reflect on silences/silencing in different forms. Perhaps they resonated in a year where a genocide is being live-streamed and attempts at speaking out are met with all manner of silencing: institutional, professional, personal. The books are also thoughtful meditations on the gendered ways in which voices are heard, when, and in what forms.

I began reading Portraits of Women in International Law (2023, edited by Immi Tallgren) with scepticism. What did this book have to offer at a time of total disillusionment with international law? I persevered and was rewarded. The essays introduce 42 fascinating women from different times in history and different parts of the world, most previously unknown to me. I was struck by the ongoing relevance of their contributions to debates about (in)equality, war and peace, the state, and international solidarity. Our foremothers too, it seems, struggled with how to engage with institutions of power, and their lessons gave me much food for thought.

While I have read a lot about the Sri Lankan war, Brotherless Night (2023) by V.V. Ganeshananthan felt different. Ganeshananthan doesn’t just highlight the gendered experience of war, she captures a different tempo. I realised that I associate war with speed. But in this case, it was the narrator’s descriptions of long periods of enforced passivity and waiting that haunted me. At the same time these roles are fulfilled with quiet strength: a contrasting form of resistance to more ‘spectacular’ violent confrontation. Reading it, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to the Ammas of the Disappeared – often viewed as tragic objects of pity – but in fact remarkable figures of strength, doggedly refusing to end their wait for answers.

The need to reimagine what agency might look like in conditions of oppression is also what struck me in Semiotics of Rape: Sexual Subjectivity and Violation in Rural India (2022) by Rupal Oza. Through an ethnography of rape allegations in Haryana, Oza confronts the ‘real’/ ‘false’ dichotomy used to characterise each case. This framework is unhelpful, Oza argues, in a context where female sexual subjectivity is completely denied. By exploring how women negotiate relationships in a society marked by severe inequality along gender, caste, and class lines, Oza opens up a provocative, but also productive, feminist agenda that might force us to think about consent and coercion in new ways.

Kiran Grewal is a human rights lawyer and academic. She is currently a Visiting Professor in the Department of Gender Studies, London School of Economics and Political Science.

If there is one book that grapples with the question of the role of the artist/writer during times of political injustice, it is a small, but little-known novel written in Portuguese, called Sostiene Pereira (meaning ‘Pereira Maintains’, 1994) by Antonio Tabucchi. Pereira is the editor of the arts page of a mediocre evening newspaper in Lisbon, who believes that avoiding censorship and toeing the line, while using subtle references to resistance through nineteenth century stories, will help him navigate state authoritarianism that is rising around him. He believes that living sensibly without risking his secure, comfortable lifestyle, is the better option, despite knowing that the opposite is what is called for. The novel takes the form of a series of testimonies by Pereira recorded, presumably, in a court of law where he is being heard for a yet unrevealed act of protest against the State of Portugal in 1938. At the start of the book, any protest by Pereira, seems unlikely and out of character. This slender, brilliant novel manages to take a clear stand about its central question with devastating humaneness and moral clarity. As Moshin Hamid says in his introduction to the book, this is “a novel with the courage to be a book about art, a book about politics, and a book about the politics of art – and the skill to achieve emotional resonances that [are] devastating”.

In August this year, Tracy Holsinger directed a poetic play written by me called Water for Kings. Her brilliant direction, using choreography and music, created a riveting performance. Inspired by what Tracy created out of Water for Kings, I returned to one of my favourite poetic-dramas: Marat/Sade: the persecution and assassination of Marat as performed by the inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the direction of the Marquis de Sade (1964) by Peter Weiss. Written in German by Weiss, the play is one of most riveting pieces of drama based on Antoine Artaud’s concept of Theatre of Cruelty but uses idioms from other forms too. It was first directed in English by Peter Brook for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1964, who said that Weiss uses “total theatre, that time-honoured notion of getting all the elements of the stage to serve the play.” The play, set within a play, juxtaposes Sade’s cruelty against the horrific outcome of the French Revolution and Marat’s rationalism. It is a chilling piece of theatre where the use of poetry heightens the experience and keeps the audience in emotional shock until the very end.

Finally, Orhan Pamuk’s The Naive and the Sentimental Novelist, capped off my reading this year. When the book first came out in 2010, I bought it for a friend who writes novels and gifted it to her without reading it as I was not interested in reading about writing novels! My interest in the novel was kindled after I worked on a novel during COVID lockdown. So, when a friend picked up this book for me during her visit to Istanbul, Pamuk’s hometown, it was just what I was waiting to read. The book is based on the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures that Pamuk delivered at Harvard and takes its title from the two categories in Friedrich Schiller’s essay, ‘On Naive and Sentimental Poetry’ (1795). The idea of the “hidden centre” of the novel, which Pamuk describes in this book on writing novels, is a fascinating concept as much as the glimpse the book offers into Pamuk’s growth as a writer from his early twenties.

Ramya Jirasinghe writes poetry, fiction and nonfiction, and she lives in Colombo.

The Best of Ruskin Bond (1994) is a fascinating collection of his prose and poetry that had me hooked from the first page on. This is a book that delivers instant entertainment and asks to be read multiple times. As entertaining as the stories in the collection, his introduction delivered in his ‘atypical’ style is filled with wit, humour, and anecdotes. “People often ask me why my style is so simple … It is clarity that I am striving to attain, not simplicity,” he writes in the introduction. Bond was born in colonial India and has lived through its postcolonial and post-independence phases; hence his stories are rich with rare glimpses of changing India and interesting insights into the lives of its people over his nine-decade lifespan. An anthology full of magic, charm, and nostalgia, I am thankful to a former colleague for gifting me his Roads to Mussoorie in 2017, which introduced me to the world of Ruskin Bond.

There cannot be a more fitting tribute than Tooth Relic of the Buddha (2022) to a nation that has been fiercely possessive of its inheritance. This “treatise”, as author Dharmaratna Herath calls it, is a revised and enlarged version of his doctoral thesis submitted in 1974 to the University of London. With a 44-page introduction, the book demands dedication from the reader. This painstakingly researched and meticulously footnoted magnum opus deserves the acclaim of a masterpiece. I learned a huge amount about a place I thought I knew well. This work is an example to anyone interested in turning an academic thesis into an accessible book.

William Dalrymple’s latest book, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World (2024) is an engaging story about South Asia and its surprising interconnectedness with the world. Dalrymple is both historian and storyteller. Instead of making tall claims using theoretical jargon, he weaves stories of peoples and geographies. For someone like myself, whose interest in reading history is not for scholarly pursuits, I find Dalrymple’s style of writing immersive and captivating.

Apsara Karunaratne is a researcher with the SAARC Cultural Centre, Colombo.

Originally published in 1926, Frederick Lewis’ Sixty Four Years in Ceylon (Tisara Publishers) is a memoir set in nineteenth century Ceylon. Lewis worked on plantations and in forestry, and the book is a candid account of his life. Taking one through the decline of Ceylon’s coffee economy, and the desperate experiments by planters for a substitute (that ended with the adoption of tea), Lewis documents the hardships faced by both the “master class” and the “coolies”. In instances, the narrative agonisingly humanises the coloniser. Lewis’ attempt for objectivity in his portrayals of peasant folk comes out well. His own position as a Ceylon-born Englishman, (who lived and is buried here), is also quite insightful. The book presents memorable accounts of colonial-life in Southeast Asian outposts of empire such as the Dutch East Indies and Singapore, where Lewis travelled for work after the fall of coffee in Ceylon. This book would interest readers of nineteenth century imperial narratives.

Jean Arasanayagam’s The Fort (2018) is a travelogue-memoir collecting the writer’s impressions of visiting Jaffna after the end of the civil war. In this book, Arasanayagam draws on absences and irrevocable changes; and how, coming home after a long absence, her family responds to these transformations. In outline, the book echoes the writer’s With Flowers in Their Hair (2015), but with a firm focus on the family. I found The Fort useful to understand the psychology of the older Arasanayagam. Instances where she articulates the thoughts of her family (like when she reads her husband’s mind on arriving by a sentimental object, now reduced to ruin) add to the book’s strengths.

B. K. S. Perera’s Gilihunu Rosa Mala (‘The Rose that was Lost’) is a Sinhala-language novel released in 2017. This is an aborted love story between a Sinhala boy and a Burgher girl set in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The novel is notable for the absence of exoticisation or the use of cultural stereotypes in portraying a cross-ethnic love story. It also treats the July 1983 riots with tremendous maturity. I found this novel to be a compelling representation of Burgher life, honouring the working class of that community with self-respect and dignity. If anyone can introduce me to this writer, I’d be grateful.

Vihanga Perera (MPhil, PhD) is Senior Lecturer in English at the University of Sri Jayewardenepura.

I began the year with Sri Lankan-American writer V. V. Ganeshananthan’s Brotherless Night (2023). I think it is one of the most important anglophone novels on Sri Lanka’s political and ethnic conflict. Set in Jaffna in the 1980s as the war breaks out, this moving novel traces the fracturing of a family — a young medical student and her four brothers — swept up by the conflict. Its nuanced exploration of what it feels like to be caught between a repressive government and brutal militants challenges binary understandings of “civilians” vs “combatants” or “terrorists”. This painstakingly researched historical fiction silences those who claim non-resident Lankans cannot engage and intervene profoundly with our country. Inviting empathy, dispelling polarisation, and stimulating important conversations, Brotherless Night exemplifies how novels can influence ethnic and political reconciliation. I hope it is being translated into Tamil and Sinhala.

One of the most memorable books I read this year is James (2024): African American author Percival Everett’s sly, subversive reimagining of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn from the point of view of the runaway slave. The original Jim’s childish, ignorant persona is revealed as a performance that conceals the real reflective, book-loving, aspirant-author “James”. A disguise he adopts to appear non-threatening to the white folk who hold his life in their hands. What remains after reading this deftly comic, entertaining satire is the irrational cruelty of racism. Shortlisted for the Booker Prize, I wish James had won.

Two years ago, on Boxing Day 2022, the British Asian writer Hanif Kureishi suffered a fall in Rome which left him paralysed below the neck. As news of his hospitalisation emerged, he began to recount his devastating experience of “becoming divorced from [himself]” in a series of harrowing, sometimes hilarious, tweets, transcribed by his son and now collected in his memoir, Shattered, published in October 2024.

As Kureishi’s biographer, this chronicle of “a broken man with a smashed body” felt almost too disturbing to read. Yet, akin to how Kureishi transmuted the whiplash of racism he experienced as a child into path-breaking fictions and films, he has created an extraordinary, miraculous account of his recent trauma. His valiant reframing of his life-changing injuries as a source of creativity reveals that his prodigious mental strength and capacity for self-reinvention remain. These motifs run deep in his oeuvre. He continues to say the unsayable and speak on behalf of unheard voices, as he now communicates the experiences of those with profound injuries to readers untouched by disability.

Ruvani Ranasinha is Professor of Global Literatures at King’s College London and the author of the first biography of Hanif Kureishi titled Hanif Kureishi: Writing the Self: A biography (Manchester University Press 2023)

You May Also Like…

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...

Gananath: Renaissance Man

R. L. Stirrat

I met Gananath in July 1969 on the day I first arrived in Sri Lanka, Edmund Leach and Stanley Tambiah having imposed...