Best Reads 2025

Collective

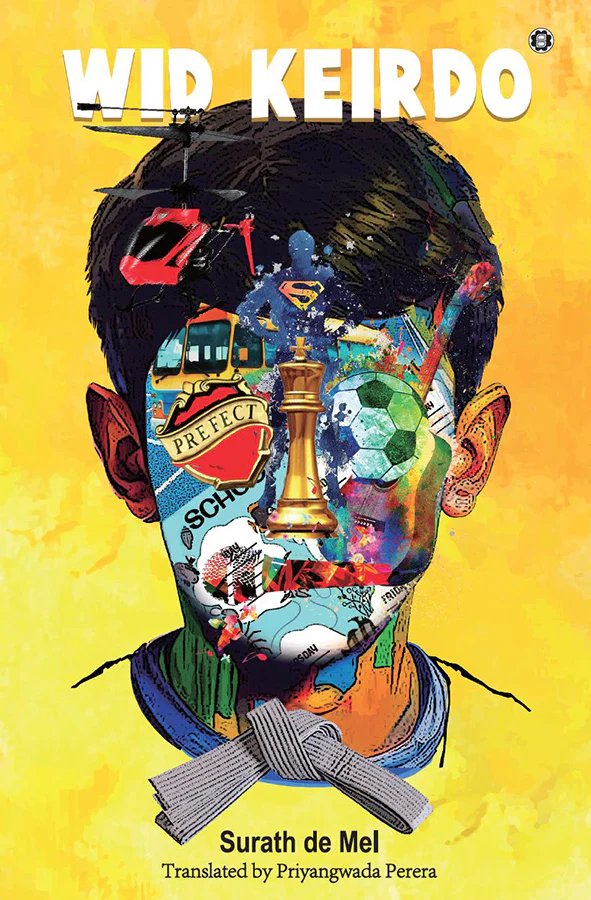

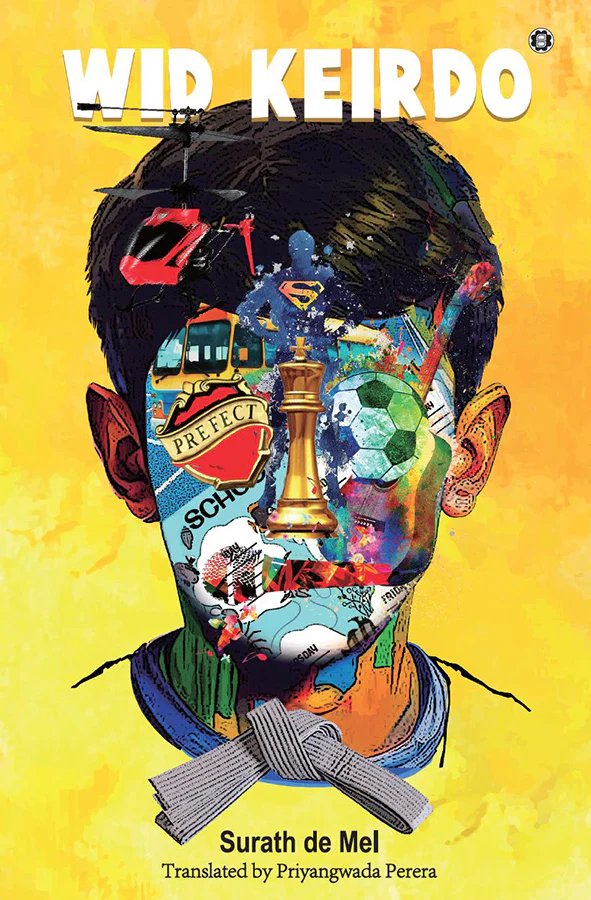

Surath de Mel’s Lamuthu Amaya translated into English by Priyangwada Perera and published as Wid Kierdo was awarded the 2025 H. A. I. Goonetilleke Prize for Literary Translation earlier this year

Due to its title, sometimes believed to be for children, the novel discusses the issues of a child who the world differently. Ahas, the protagonist finds his every thought and action is in direct contradiction to what his parents, teachers, or any regular adult believes he should do. The book relates the constant struggle of an individual to be true to himself despite overwhelming odds. For too long Sri Lankan writing has been expected to be weighty to be taken seriously. I think this book will surprise many with its deft, light touch that tackles a serious subject with humour and sensitivity.

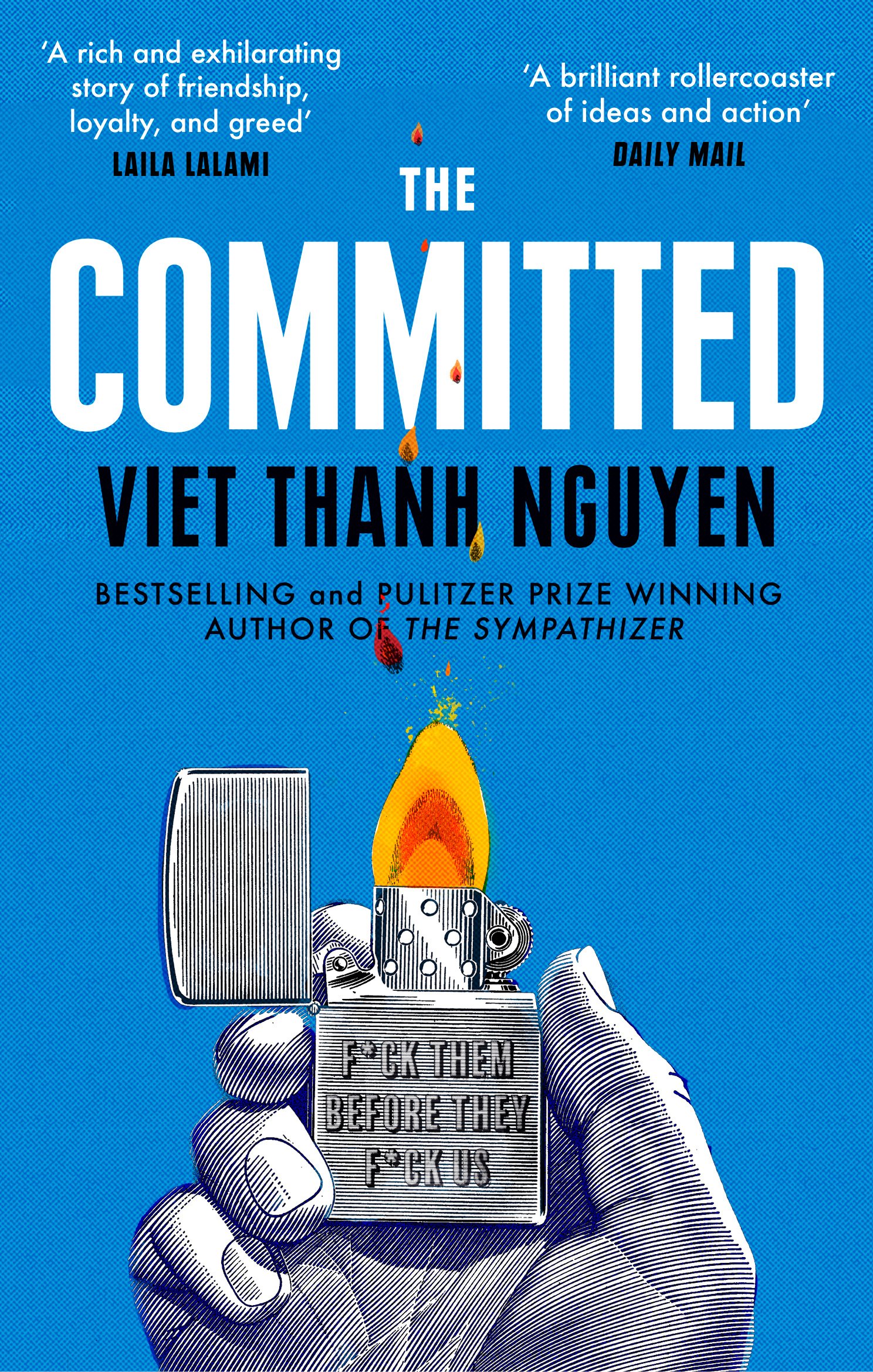

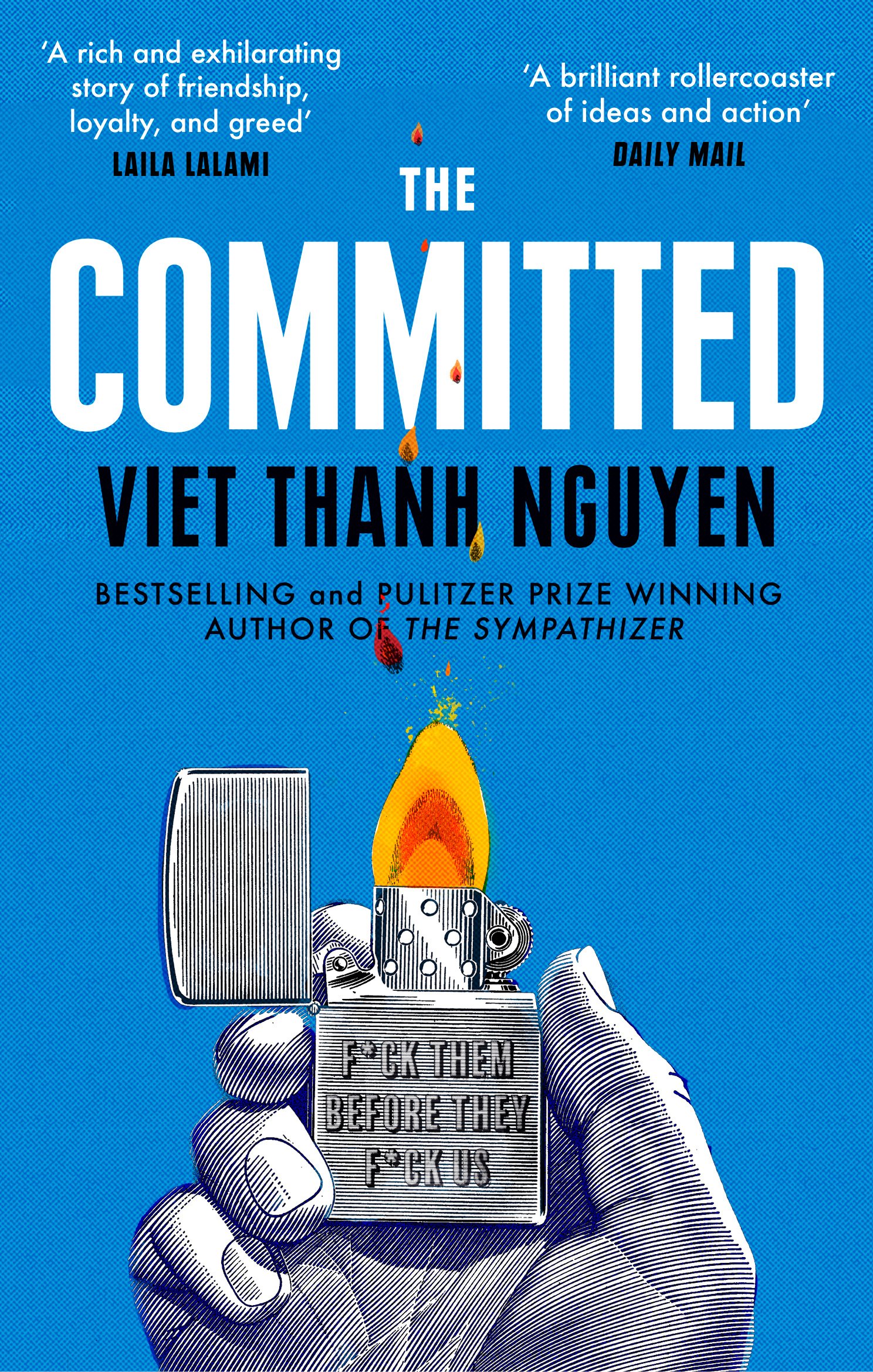

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen was published around the same time as Shehan Karunatilaka’s Seven Moons of Maali Almeida and I was struck by the similarities of violence, humour and political commentary that is common to both. However, Nguyen engages with a series of philosophical theories that talk about capitalism, communism, global power structures, and geopolitics, as well. The reader is given a good map of what Vietnam went through historically; and the colonial legacy imprinted on former imperial possessions. It highlights the subversion of power, law and order within that system. The ensuing diatribe is all the more enjoyable because the protagonist is an intelligent, witty, feisty hero who leaves you breathless at his near escapes in a rollercoaster journey. To me it is a masterpiece of polemic and conversation that highlights the power dynamics of global South and North in a most enjoyable manner.

There is nothing like a beautiful book cover to induce one to read a book and The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekera is just that! In this work of speculative fiction, one is quick to see the familiar and unfamiliar myths of South Asia that pepper this wild ride of a story set in the world of Luriat; the city navigated by the unlikely hero Fetter, burdened by his complex and powerful lineage. The language, prescription and situation the author weaves through the book spins a tight web around the reader, so that while you are grappling with one incident, you are drawn into another, just as captivating.

Ameena Hussein is a writer of fiction and non-fiction and the co-founder of the Perera Hussein Publishing House.

Surath de Mel’s Lamuthu Amaya translated into English by Priyangwada Perera and published as Wid Kierdo was awarded the 2025 H. A. I. Goonetilleke Prize for Literary Translation earlier this year

Due to its title, sometimes believed to be for children, the novel discusses the issues of a child who the world differently. Ahas, the protagonist finds his every thought and action is in direct contradiction to what his parents, teachers, or any regular adult believes he should do. The book relates the constant struggle of an individual to be true to himself despite overwhelming odds. For too long Sri Lankan writing has been expected to be weighty to be taken seriously. I think this book will surprise many with its deft, light touch that tackles a serious subject with humour and sensitivity.

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen was published around the same time as Shehan Karunatilaka’s Seven Moons of Maali Almeida and I was struck by the similarities of violence, humour and political commentary that is common to both. However, Nguyen engages with a series of philosophical theories that talk about capitalism, communism, global power structures, and geopolitics, as well. The reader is given a good map of what Vietnam went through historically; and the colonial legacy imprinted on former imperial possessions. It highlights the subversion of power, law and order within that system. The ensuing diatribe is all the more enjoyable because the protagonist is an intelligent, witty, feisty hero who leaves you breathless at his near escapes in a rollercoaster journey. To me it is a masterpiece of polemic and conversation that highlights the power dynamics of global South and North in a most enjoyable manner.

There is nothing like a beautiful book cover to induce one to read a book and The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekera is just that! In this work of speculative fiction, one is quick to see the familiar and unfamiliar myths of South Asia that pepper this wild ride of a story set in the world of Luriat; the city navigated by the unlikely hero Fetter, burdened by his complex and powerful lineage. The language, prescription and situation the author weaves through the book spins a tight web around the reader, so that while you are grappling with one incident, you are drawn into another, just as captivating.

Ameena Hussein is a writer of fiction and non-fiction and the co-founder of the Perera Hussein Publishing House.

Ameena Hussein is a writer of fiction and non-fiction and the co-founder of the Perera Hussein Publishing House.

Surath de Mel’s Lamuthu Amaya translated into English by Priyangwada Perera and published as Wid Kierdo was awarded the 2025 H. A. I. Goonetilleke Prize for Literary Translation earlier this year

Due to its title, sometimes believed to be for children, the novel discusses the issues of a child who the world differently. Ahas, the protagonist finds his every thought and action is in direct contradiction to what his parents, teachers, or any regular adult believes he should do. The book relates the constant struggle of an individual to be true to himself despite overwhelming odds. For too long Sri Lankan writing has been expected to be weighty to be taken seriously. I think this book will surprise many with its deft, light touch that tackles a serious subject with humour and sensitivity.

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen was published around the same time as Shehan Karunatilaka’s Seven Moons of Maali Almeida and I was struck by the similarities of violence, humour and political commentary that is common to both. However, Nguyen engages with a series of philosophical theories that talk about capitalism, communism, global power structures, and geopolitics, as well. The reader is given a good map of what Vietnam went through historically; and the colonial legacy imprinted on former imperial possessions. It highlights the subversion of power, law and order within that system. The ensuing diatribe is all the more enjoyable because the protagonist is an intelligent, witty, feisty hero who leaves you breathless at his near escapes in a rollercoaster journey. To me it is a masterpiece of polemic and conversation that highlights the power dynamics of global South and North in a most enjoyable manner.

There is nothing like a beautiful book cover to induce one to read a book and The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekera is just that! In this work of speculative fiction, one is quick to see the familiar and unfamiliar myths of South Asia that pepper this wild ride of a story set in the world of Luriat; the city navigated by the unlikely hero Fetter, burdened by his complex and powerful lineage. The language, prescription and situation the author weaves through the book spins a tight web around the reader, so that while you are grappling with one incident, you are drawn into another, just as captivating.

Carrie N. Baker’s The Women’s Movement against Sexual Harassment (2008) was one of the most inspiring books I read this year. Baker sets out the story of the social movement against sexual harassment as it emerged in the 1970s in the US and the numerous challenges the movement faced in its effort to convince the employers, workplaces and the judiciary – in short, a world predominantly of men – that sexual harassment is a grave violation of the rights and dignity of women. Importantly, Baker points to the need to confront the powerful biases that continue to shape the opinions not only of the public but also of institutions such as the judiciary; biases that have the unfortunate consequences of tolerating, and perpetuating, sexual harassment. It is a book which we would need to revisit during our long and, sadly, unfinished struggles against sexual harassment and other forms of violence against women.

Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface (2023) stands out as the most gripping novel I read this year. Athena Liu, a young and famous author, dies due to a freak accident. A casual friend, June Hayward, finds Liu’s unpublished manuscript, edits and publishes it in her own name, achieving stardom. It is a fast-moving story, which raises profound and intriguing questions about the publishing industry, copying and plagiarism, and the inner conscience of authors. The book is extremely appealing, given the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the numerous challenges posed by AI which have begun to question the authenticity and ethics of authors. Kuang is a very interesting author, with an academic bent. I am looking forward to reading her most recent work, Katabasis, in 2026.

Then there was Arundhati Roy’s memoir, Mother Mary Comes To Me (2025). What an absolute delight! It is a moving meditation on the author’s tense and troubled relationship with her mother, Mary Roy, who was a teacher, activist, and independent-minded woman who, strangely, appeared to detest and love her daughter at the same time. It is a very courageous piece of writing. Not many could say about a parent what Roy has, with such elegance and tenderness. And this memoir also explains, in subtle ways, how Roy’s relationship with her mother has shaped her own thinking about life, human relationships, activism, and even feminism. I am truly glad to have read it. This even makes the task of re-reading Roy’s earlier writing an exciting prospect.

Kalana Senaratne is currently the Head of the Department of Law, University of Peradeniya, and a Member of the National Commission on Women.

Carrie N. Baker’s The Women’s Movement against Sexual Harassment (2008) was one of the most inspiring books I read this year. Baker sets out the story of the social movement against sexual harassment as it emerged in the 1970s in the US and the numerous challenges the movement faced in its effort to convince the employers, workplaces and the judiciary – in short, a world predominantly of men – that sexual harassment is a grave violation of the rights and dignity of women. Importantly, Baker points to the need to confront the powerful biases that continue to shape the opinions not only of the public but also of institutions such as the judiciary; biases that have the unfortunate consequences of tolerating, and perpetuating, sexual harassment. It is a book which we would need to revisit during our long and, sadly, unfinished struggles against sexual harassment and other forms of violence against women.

Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface (2023) stands out as the most gripping novel I read this year. Athena Liu, a young and famous author, dies due to a freak accident. A casual friend, June Hayward, finds Liu’s unpublished manuscript, edits and publishes it in her own name, achieving stardom. It is a fast-moving story, which raises profound and intriguing questions about the publishing industry, copying and plagiarism, and the inner conscience of authors. The book is extremely appealing, given the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the numerous challenges posed by AI which have begun to question the authenticity and ethics of authors. Kuang is a very interesting author, with an academic bent. I am looking forward to reading her most recent work, Katabasis, in 2026.

Then there was Arundhati Roy’s memoir, Mother Mary Comes To Me (2025). What an absolute delight! It is a moving meditation on the author’s tense and troubled relationship with her mother, Mary Roy, who was a teacher, activist, and independent-minded woman who, strangely, appeared to detest and love her daughter at the same time. It is a very courageous piece of writing. Not many could say about a parent what Roy has, with such elegance and tenderness. And this memoir also explains, in subtle ways, how Roy’s relationship with her mother has shaped her own thinking about life, human relationships, activism, and even feminism. I am truly glad to have read it. This even makes the task of re-reading Roy’s earlier writing an exciting prospect.

Kalana Senaratne is currently the Head of the Department of Law, University of

Peradeniya, and a Member of the National Commission on Women.

Kalana Senaratne is currently the Head of the Department of Law, University of

Peradeniya, and a Member of the National Commission on Women.

Carrie N. Baker’s The Women’s Movement against Sexual Harassment (2008) was one of the most inspiring books I read this year. Baker sets out the story of the social movement against sexual harassment as it emerged in the 1970s in the US and the numerous challenges the movement faced in its effort to convince the employers, workplaces and the judiciary – in short, a world predominantly of men – that sexual harassment is a grave violation of the rights and dignity of women. Importantly, Baker points to the need to confront the powerful biases that continue to shape the opinions not only of the public but also of institutions such as the judiciary; biases that have the unfortunate consequences of tolerating, and perpetuating, sexual harassment. It is a book which we would need to revisit during our long and, sadly, unfinished struggles against sexual harassment and other forms of violence against women.

Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface (2023) stands out as the most gripping novel I read this year. Athena Liu, a young and famous author, dies due to a freak accident. A casual friend, June Hayward, finds Liu’s unpublished manuscript, edits and publishes it in her own name, achieving stardom. It is a fast-moving story, which raises profound and intriguing questions about the publishing industry, copying and plagiarism, and the inner conscience of authors. The book is extremely appealing, given the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the numerous challenges posed by AI which have begun to question the authenticity and ethics of authors. Kuang is a very interesting author, with an academic bent. I am looking forward to reading her most recent work, Katabasis, in 2026.

Then there was Arundhati Roy’s memoir, Mother Mary Comes To Me (2025). What an absolute delight! It is a moving meditation on the author’s tense and troubled relationship with her mother, Mary Roy, who was a teacher, activist, and independent-minded woman who, strangely, appeared to detest and love her daughter at the same time. It is a very courageous piece of writing. Not many could say about a parent what Roy has, with such elegance and tenderness. And this memoir also explains, in subtle ways, how Roy’s relationship with her mother has shaped her own thinking about life, human relationships, activism, and even feminism. I am truly glad to have read it. This even makes the task of re-reading Roy’s earlier writing an exciting prospect.

I love the Japanese style of bringing magic to the ordinary in very simple language. Before the Coffee Gets Cold (2015) by Toshikazu Kawaguchi had all that. It’s a story of a café where people could time-travel either to the past or the future. They go mostly to the past—because as time passes, people realise what a lot has been lost so casually by not seeing the significance of small moments in life. Time-travel has some rules attached. The main one is that nothing can be changed. Even so, revisiting the past allows for a different interpretation of events that follow. It opens possibilities for the future.

The Covenant of Water (2023) by Abraham Verghese is a history of a place and its changes, captured in three generations. It is beautifully done with a love story and an eerie mystery running through it. The lush land of a house in Travancore is described in gorgeous detail, together with the life of its inhabitants. The sense of place is perhaps the strongest feature here (the plot, though carefully crafted, has too many coincidences to be taken too seriously). For captivating the reader, and for transporting her to a world with the power to fill all five senses of touch, sound, smell, taste, and hearing, Verghese has excelled. The mystery is solved at the end through science by the granddaughter of the matriarch, whose story we have followed and who elephants and people love.

Maurice (1971) has the same sense of perfection in writing that E.M. Forster has in his other novels. It’s a story of a gay love affair; the intensity of which peters out for one party as he steps into the role of a landed gentleman, and his past passion consigned to a mere episode in the journey of maturing. This doesn’t happen to the other man, and, though he disappears into the night in the last scene and is not heard of again, he still remains true to himself and in love, which Forster seems to think a fair price to pay for invisibility. Given the pro- and anti-LGBTQ waves in Sri Lanka in recent times, the human aspect should be of interest to anyone.

Madhubhashini Disanayaka Ratnayake is a writer of fiction, senior lecturer in the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, English Language Teaching activist, and translator.

Madhubhashini Disanayaka Ratnayake is a writer of fiction, senior lecturer in the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, English Language Teaching activist, and translator.

I love the Japanese style of bringing magic to the ordinary in very simple language. Before the Coffee Gets Cold (2015) by Toshikazu Kawaguchi had all that. It’s a story of a café where people could time-travel either to the past or the future. They go mostly to the past—because as time passes, people realise what a lot has been lost so casually by not seeing the significance of small moments in life. Time-travel has some rules attached. The main one is that nothing can be changed. Even so, revisiting the past allows for a different interpretation of events that follow. It opens possibilities for the future.

The Covenant of Water (2023) by Abraham Verghese is a history of a place and its changes, captured in three generations. It is beautifully done with a love story and an eerie mystery running through it. The lush land of a house in Travancore is described in gorgeous detail, together with the life of its inhabitants. The sense of place is perhaps the strongest feature here (the plot, though carefully crafted, has too many coincidences to be taken too seriously). For captivating the reader, and for transporting her to a world with the power to fill all five senses of touch, sound, smell, taste, and hearing, Verghese has excelled. The mystery is solved at the end through science by the granddaughter of the matriarch, whose story we have followed and who elephants and people love.

Maurice (1971) has the same sense of perfection in writing that E.M. Forster has in his other novels. It’s a story of a gay love affair; the intensity of which peters out for one party as he steps into the role of a landed gentleman, and his past passion consigned to a mere episode in the journey of maturing. This doesn’t happen to the other man, and, though he disappears into the night in the last scene and is not heard of again, he still remains true to himself and in love, which Forster seems to think a fair price to pay for invisibility. Given the pro- and anti-LGBTQ waves in Sri Lanka in recent times, the human aspect should be of interest to anyone.

Of the books I read this year, A Little Life (2015) by Hanya Yanagihara is my favourite. The heartache that permeates the plot is so raw that I found myself having to set it aside for weeks at a time before I could pick it up again. Yanagihara’s focus is on a cohort of friends; however, the emotional weight of the novel is vested primarily in Jude. His story of surviving sexual abuse, grooming, and rape, is harrowing. Yanagihara’s images of assault and self-harm are visceral, but it is her depiction of the resulting trauma that I found skilled. She asserts that trauma is individual, highlighting that it is survivors who ultimately decide how to navigate their lived realities. Jude exemplifies that, while love is essential in dealing with trauma, some experiences shatter the limits of human endurance.

Amidst rising anti-trans sentiment and politics, Juno Roche’s Gender Explorers (2020) is an essential read. Written as a series of interviews with trans and non-binary children and youth, the book offers a fresh perspective of the gender-queer experience. The decision to centre the gender experiences of young people is poignant. It legitimises the autonomy they have in exploring and deciding their gender and, importantly, identifies them as self-aware enough to make such decisions for themselves. I relished its portrayal of queer joy. The euphoria the interviewees experience at such a young age is palpable; it establishes itself as a rebellious contrast to the egregious images of gender queerness propagated by our often ignorant and unimaginative society.

I was drawn to Babel (2022) by R.F Kuang due to its unique, layered portrayal of colonisation. Through Robin, his group of friends, and their complex relationship with Babel, a fictitious language institute in England, Kuang explores how the coloniser moulds the identity of the colonised. The imbalanced power dynamic between the two generates the tension that fuels the novel. It underpins all of Robin’s relationships, especially with his guardian Professor Lovell, who transports him from Canton to Oxford, as a politico-academic weapon of the Empire. I enjoyed how Kuang subtly frames one of the novel’s central preoccupations: can rebellion ever be peaceful, or, for success, must it always be violent?

Nubendra Liyanage is an undergraduate at the Faculty of Arts, University of Colombo and an intern at the Social Scientists’ Association.

Of the books I read this year, A Little Life (2015) by Hanya Yanagihara is my favourite. The heartache that permeates the plot is so raw that I found myself having to set it aside for weeks at a time before I could pick it up again. Yanagihara’s focus is on a cohort of friends; however, the emotional weight of the novel is vested primarily in Jude. His story of surviving sexual abuse, grooming, and rape, is harrowing. Yanagihara’s images of assault and self-harm are visceral, but it is her depiction of the resulting trauma that I found skilled. She asserts that trauma is individual, highlighting that it is survivors who ultimately decide how to navigate their lived realities. Jude exemplifies that, while love is essential in dealing with trauma, some experiences shatter the limits of human endurance.

Amidst rising anti-trans sentiment and politics, Juno Roche’s Gender Explorers (2020) is an essential read. Written as a series of interviews with trans and non-binary children and youth, the book offers a fresh perspective of the gender-queer experience. The decision to centre the gender experiences of young people is poignant. It legitimises the autonomy they have in exploring and deciding their gender and, importantly, identifies them as self-aware enough to make such decisions for themselves. I relished its portrayal of queer joy. The euphoria the interviewees experience at such a young age is palpable; it establishes itself as a rebellious contrast to the egregious images of gender queerness propagated by our often ignorant and unimaginative society.

I was drawn to Babel (2022) by R.F Kuang due to its unique, layered portrayal of colonisation. Through Robin, his group of friends, and their complex relationship with Babel, a fictitious language institute in England, Kuang explores how the coloniser moulds the identity of the colonised. The imbalanced power dynamic between the two generates the tension that fuels the novel. It underpins all of Robin’s relationships, especially with his guardian Professor Lovell, who transports him from Canton to Oxford, as a politico-academic weapon of the Empire. I enjoyed how Kuang subtly frames one of the novel’s central preoccupations: can rebellion ever be peaceful, or, for success, must it always be violent?

Nubendra Liyanage is an undergraduate at the Faculty of Arts, University of Colombo and an intern at the Social Scientists’ Association.

Nubendra Liyanage is an undergraduate at the Faculty of Arts, University of Colombo and an intern at the Social Scientists’ Association.

Of the books I read this year, A Little Life (2015) by Hanya Yanagihara is my favourite. The heartache that permeates the plot is so raw that I found myself having to set it aside for weeks at a time before I could pick it up again. Yanagihara’s focus is on a cohort of friends; however, the emotional weight of the novel is vested primarily in Jude. His story of surviving sexual abuse, grooming, and rape, is harrowing. Yanagihara’s images of assault and self-harm are visceral, but it is her depiction of the resulting trauma that I found skilled. She asserts that trauma is individual, highlighting that it is survivors who ultimately decide how to navigate their lived realities. Jude exemplifies that, while love is essential in dealing with trauma, some experiences shatter the limits of human endurance.

Amidst rising anti-trans sentiment and politics, Juno Roche’s Gender Explorers (2020) is an essential read. Written as a series of interviews with trans and non-binary children and youth, the book offers a fresh perspective of the gender-queer experience. The decision to centre the gender experiences of young people is poignant. It legitimises the autonomy they have in exploring and deciding their gender and, importantly, identifies them as self-aware enough to make such decisions for themselves. I relished its portrayal of queer joy. The euphoria the interviewees experience at such a young age is palpable; it establishes itself as a rebellious contrast to the egregious images of gender queerness propagated by our often ignorant and unimaginative society.

I was drawn to Babel (2022) by R.F Kuang due to its unique, layered portrayal of colonisation. Through Robin, his group of friends, and their complex relationship with Babel, a fictitious language institute in England, Kuang explores how the coloniser moulds the identity of the colonised. The imbalanced power dynamic between the two generates the tension that fuels the novel. It underpins all of Robin’s relationships, especially with his guardian Professor Lovell, who transports him from Canton to Oxford, as a politico-academic weapon of the Empire. I enjoyed how Kuang subtly frames one of the novel’s central preoccupations: can rebellion ever be peaceful, or, for success, must it always be violent?

Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me (2025), I found to be cognitively brilliant while lacking in emotional depth. Roy has reached the important early stage of healing: of acknowledging trauma and its triggers. She has not, however, been able to move to a deeper place of seeing, feeling, and perhaps one day living a life, where the mantra for ‘survival’—“anything can happen to anyone, it’s best to be prepared”–-is not the last word. For those who have followed her work, it leaves us wanting more. What of her role in making some movements part of big H history, and not others? What did fame and money do to her writing and her political choices? These are some of the reflections I wish were part of her memoir.

Shailaja Paik’s idea of the ‘stickiness’ of caste, even though multiple socio-historical processes may reduce or change its role in our lives, is brilliant! The Vulgarity of Caste (2022) is pathbreaking methodologically and theoretically. Paik stays with the embodied experience of caste which she then historicises without simplification. It is such embracing of complexity that can lead to scholarship, thinking, and hopefully change, that can annihilate—not just reframe—oppressive structures such as caste! For Sri Lankans, it is a call to ask, what identities/experiences ‘sticks’ to you; even if historical processes, discourses and normative constructions, deny or diminish their existence in you and your society.? Awareness of positionalities and its complexity is imperative, if it is to be used courageously and creatively, towards justice and change.

I read V. V. Ganeshananthan’s Brotherless Night (2023) while translating it into Tamil in my head. Her book portrays the absolute horror of the Sri Lankan state, Sinhala majoritarianism and at the same time the complex, raw, and manipulative nature of Tamil nationalism. This book managed to touch the experience of how Tamils experienced the war, through reality-inspired fiction set in Jaffna from the early 1980s onwards. The choice to do so through fictionalised versions of Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, Thileepan and others, is a brilliant use of literary tools. The Tamil-speaking people of this island who lived through the war need these complex renditions of history to take stock of what happened, while moving towards recreating identities in a diverse and vibrant way for generations to come.

Ponni Arasu is an independent scholar, activist, expressive arts therapist, translator, and theatre artist.

Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me (2025), I found to be cognitively brilliant while lacking in emotional depth. Roy has reached the important early stage of healing: of acknowledging trauma and its triggers. She has not, however, been able to move to a deeper place of seeing, feeling, and perhaps one day living a life, where the mantra for ‘survival’—“anything can happen to anyone, it’s best to be prepared”–-is not the last word. For those who have followed her work, it leaves us wanting more. What of her role in making some movements part of big H history, and not others? What did fame and money do to her writing and her political choices? These are some of the reflections I wish were part of her memoir.

Shailaja Paik’s idea of the ‘stickiness’ of caste, even though multiple socio-historical processes may reduce or change its role in our lives, is brilliant! The Vulgarity of Caste (2022) is pathbreaking methodologically and theoretically. Paik stays with the embodied experience of caste which she then historicises without simplification. It is such embracing of complexity that can lead to scholarship, thinking, and hopefully change, that can annihilate—not just reframe—oppressive structures such as caste! For Sri Lankans, it is a call to ask, what identities/experiences ‘sticks’ to you; even if historical processes, discourses and normative constructions, deny or diminish their existence in you and your society.? Awareness of positionalities and its complexity is imperative, if it is to be used courageously and creatively, towards justice and change.

I read V. V. Ganeshananthan’s Brotherless Night (2023) while translating it into Tamil in my head. Her book portrays the absolute horror of the Sri Lankan state, Sinhala majoritarianism and at the same time the complex, raw, and manipulative nature of Tamil nationalism. This book managed to touch the experience of how Tamils experienced the war, through reality-inspired fiction set in Jaffna from the early 1980s onwards. The choice to do so through fictionalised versions of Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, Thileepan and others, is a brilliant use of literary tools. The Tamil-speaking people of this island who lived through the war need these complex renditions of history to take stock of what happened, while moving towards recreating identities in a diverse and vibrant way for generations to come.

Ponni Arasu is an independent scholar, activist, expressive arts therapist, translator, and theatre artist.

Ponni Arasu is an independent scholar, activist, expressive arts therapist, translator, and theatre artist.

Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me (2025), I found to be cognitively brilliant while lacking in emotional depth. Roy has reached the important early stage of healing: of acknowledging trauma and its triggers. She has not, however, been able to move to a deeper place of seeing, feeling, and perhaps one day living a life, where the mantra for ‘survival’—“anything can happen to anyone, it’s best to be prepared”–-is not the last word. For those who have followed her work, it leaves us wanting more. What of her role in making some movements part of big H history, and not others? What did fame and money do to her writing and her political choices? These are some of the reflections I wish were part of her memoir.

Shailaja Paik’s idea of the ‘stickiness’ of caste, even though multiple socio-historical processes may reduce or change its role in our lives, is brilliant! The Vulgarity of Caste (2022) is pathbreaking methodologically and theoretically. Paik stays with the embodied experience of caste which she then historicises without simplification. It is such embracing of complexity that can lead to scholarship, thinking, and hopefully change, that can annihilate—not just reframe—oppressive structures such as caste! For Sri Lankans, it is a call to ask, what identities/experiences ‘sticks’ to you; even if historical processes, discourses and normative constructions, deny or diminish their existence in you and your society.? Awareness of positionalities and its complexity is imperative, if it is to be used courageously and creatively, towards justice and change.

I read V. V. Ganeshananthan’s Brotherless Night (2023) while translating it into Tamil in my head. Her book portrays the absolute horror of the Sri Lankan state, Sinhala majoritarianism and at the same time the complex, raw, and manipulative nature of Tamil nationalism. This book managed to touch the experience of how Tamils experienced the war, through reality-inspired fiction set in Jaffna from the early 1980s onwards. The choice to do so through fictionalised versions of Dr. Rajani Thiranagama, Thileepan and others, is a brilliant use of literary tools. The Tamil-speaking people of this island who lived through the war need these complex renditions of history to take stock of what happened, while moving towards recreating identities in a diverse and vibrant way for generations to come.

The three works that stay with me in 2025 each express a concern for “place” and the “human”. They’ve left me with the conviction that the human isn’t a place naturally occupied, but one to be actively sought or forged.

Enzo Traverso’s Gaza Faces History (2024) is a critical reflection on what Gaza means for our historical present. Traverso lucidly shows how the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people by the Israeli settler state throws into question the dominant nexus between history, humanity, and justice, established after World War 2 and the Cold War. Gaza bears witness to how yesterday’s “victims” are today’s “perpetrators”; and to how a people once violently expelled from Europe have become an adulated symbol of the West—as the discourse of “anti-Semitism” is weaponised against an alleged “Islamic barbarism”, conceived as an existential threat to Western civilisation.

Over the past two years, I’ve been trying to rethink the common-sense divide between settlers and tourists. Especially where tourism profoundly transforms the structures of a place; so much so that they are reshaped to serve potential tourists, who are free to come and go—and even profit financially—unlike locals, who lack the same kinds of freedom, mobility, and capital. I’ve named this “settler tourism”. For its conceptualisation, I’ve returned to Jamaica Kincaid’s A Small Place (1988). This little classic is an incisive portrait of her native Antigua: an island inscribed by colonialism, transatlantic slavery, and, of course, tourism. In Kincaid’s telling, Antigua becomes a “small place”, where white tourists seek respite from the banality and corruption of “large places”—even as the island’s people are denied what tourists take for granted. This resonates well with Sri Lanka.

A Psychoanalysis for a Reemergent Humanity (2025), edited by Lucy Cantin, Jeffrey Librett, and Tracy McNulty, is a collection of essays on the metapsychology of the Haitian-Quebecois psychoanalyst Willy Apollon. The essays centre the idea of the human, and powerfully envision a new psychoanalysis, surpassing the ethnocentrisms of both Freud and Lacan. This new psychoanalysis can be enlisted for a renewed human quest, as globalisation, advances in digital technology, and ecological crises call into question the ability of cultures and civilisations to interpret and delimit humanity. This text sustains hope in a possible place for the human, a space for autonomy, as we face—in unequal ways—newfound challenges that are no longer national or even global, but planetary.

Praveen Tilakaratne is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Cornell University.

Praveen Tilakaratne is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Cornell University.

The three works that stay with me in 2025 each express a concern for “place” and the “human”. They’ve left me with the conviction that the human isn’t a place naturally occupied, but one to be actively sought or forged.

Enzo Traverso’s Gaza Faces History (2024) is a critical reflection on what Gaza means for our historical present. Traverso lucidly shows how the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people by the Israeli settler state throws into question the dominant nexus between history, humanity, and justice, established after World War 2 and the Cold War. Gaza bears witness to how yesterday’s “victims” are today’s “perpetrators”; and to how a people once violently expelled from Europe have become an adulated symbol of the West—as the discourse of “anti-Semitism” is weaponised against an alleged “Islamic barbarism”, conceived as an existential threat to Western civilisation.

Over the past two years, I’ve been trying to rethink the common-sense divide between settlers and tourists. Especially where tourism profoundly transforms the structures of a place; so much so that they are reshaped to serve potential tourists, who are free to come and go—and even profit financially—unlike locals, who lack the same kinds of freedom, mobility, and capital. I’ve named this “settler tourism”. For its conceptualisation, I’ve returned to Jamaica Kincaid’s A Small Place (1988). This little classic is an incisive portrait of her native Antigua: an island inscribed by colonialism, transatlantic slavery, and, of course, tourism. In Kincaid’s telling, Antigua becomes a “small place”, where white tourists seek respite from the banality and corruption of “large places”—even as the island’s people are denied what tourists take for granted. This resonates well with Sri Lanka.

A Psychoanalysis for a Reemergent Humanity (2025), edited by Lucy Cantin, Jeffrey Librett, and Tracy McNulty, is a collection of essays on the metapsychology of the Haitian-Quebecois psychoanalyst Willy Apollon. The essays centre the idea of the human, and powerfully envision a new psychoanalysis, surpassing the ethnocentrisms of both Freud and Lacan. This new psychoanalysis can be enlisted for a renewed human quest, as globalisation, advances in digital technology, and ecological crises call into question the ability of cultures and civilisations to interpret and delimit humanity. This text sustains hope in a possible place for the human, a space for autonomy, as we face—in unequal ways—newfound challenges that are no longer national or even global, but planetary.

You May Also Like…

Samanmali: A Life on the Frontlines of Women’s Struggles and Working-Class Resistance

Kumudini Samuel

H. I. Samanmali (‘Saman’) passed away on 11 November, after withstanding years of illness with quiet strength. For...

The Im/Possibility of Justice in the Current Global Order

Kiran Kaur Grewal

It is such an honour to deliver the 2025 Rajani Thiranagama Memorial Lecture.[1] Having worked in human rights for...

The Great Flood

B. Skanthakumar

Cyclone Ditwah ripped through Sri Lanka between 27 and 29 November. The toll is devastating. Seven days later, the...