Left Feminism in and after the Aragalaya

Chulani Kodikara and Amalini de Sayrah

The Aragalaya/Porattam/Struggle of 2022 constitutes an unprecedented event in democratic mobilisation and protest politics in Sri Lanka’s history, culminating in the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. More than three years after his removal from office, a growing body of scholarship has examined the multiplicity of acts, events, and practices that comprised the Aragalaya, underscoring the impossibility of reducing it to a singular, centralised structure or organisational entity (Arulingam and de Silva 2023; Balendra 2025; CPA – Social Indicator 2023; Kumarasinghe 2025; Rambukwella 2024). While the rallying cries of “Go Gota, Go Go!”, “Go Gota, Go Home!” or “Kaputu Kaak Kaak Kaak – Basil, Basil, Basil” served as unifying slogans that cut across ethnic, class, generational, and gender divides, the movement also gave rise to another resounding call: one for system change.

“System change” however, meant different things to different people and generated a multitude of “protests within the protest”, each articulating distinct grievances, aspirations, and political imaginaries. Analysing responses from 1000 protesters polled while the Aragalaya was ongoing, Social Indicator, the survey research unit of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) has argued that “the movement created room for struggles previously considered peripheral to the majoritarian core” (CPA – Social Indicator 2023: 1).

In a similar vein, Arulingam and de Silva (2023: 53), feminist activists who were protesting and organising events within the Aragalaya, contend that “with all the limitations inherent to Sri Lankan politics, the Galle Face occupation site (‘Gota Go Gama’, hereafter GGG) opened up spaces to sections of society who would otherwise be denied a political voice and remain excluded from protest sites”. Among these are a number of events and acts of solidarity that cut “across deep seated ethnic and religious divides that have plagued the country for many decades” (CPA – Social Indicator 2023: 26; see also Balendra 2025; Satkunanathan 2022: 549-550).

For instance, during the month of Ramadan, which fell during the first few weeks of the Aragalaya in April/May 2022, Muslim men and women broke fast together with protesters of other faiths and none, who were invited to join them at Galle Face Green and Independence Square in Colombo. On 18 May, a group organised the first ever Mullivaikkal commemoration of its scale outside of the north and east in memory of Tamils who had been killed and disappeared during the final phase of Sri Lanka’s civil war. They lit a flame, shared kanji[1], and scattered flowers in the sea. One of the most poignant moments of the commemoration was a powerful rendition of Nam Pārpomē, a Tamil version of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s Hum Dekhenge translated by Mangai Arasu and Ponni Arasu, and sung by Swasthika Arulingam (Perera 2023: 3). In yet another moment of ethnic solidarity, Aragalaya protesters sang along to the national anthem in Tamil. The Aragalaya also witnessed a vibrant Pride march. Pasan Jayasinghe (2022) later noted in a twitter thread: “Pride events here are usually discrete (sic) & closed doors affairs, by necessity because of watchful authorities & queerphobes”, yet this march explicitly framed as part of the Aragalaya challenged the bigotry of state and society with “colour and noise and joy”.

Swasthika Arulingam, Mullivaikal commemoration, 18 May 2022.

Photo credit: Amalini de Sayrah

Women participated in unprecedented numbers in the Aragalaya right from the very outset. They were on the frontlines of small neighbourhood protests and the “kitchen laments” that erupted in many different sites across the country even before the occupation of Galle Face Green on 9 April. Women’s rights activists also brought their own histories of struggle—some of which were decades old—to their engagement with the Aragalaya. In the process, these issues were transformed into national issues (Arulingam and de Silva 2023: 54).

Drawing inspiration from and building on the work of Arulingam and de Silva, in this essay[2] we peer beneath the surface of the Aragalaya with a “feminist curiosity” (Talcott and Collins 2012) to illuminate three strands of feminist activism and resistance relating to labour and the economy that have curiously not received the attention that it deserves in the current scholarship on the Aragalaya: by women export factory workers; the microfinance crisis, which has overwhelmingly affected rural women; and the gendered implications of the economic crisis.

Reflecting on this activism, we argue that several small groups of organised feminist activists through their interventions and initiatives consciously and deliberately carved out a space to make their struggles visible to a wider, national audience within the Aragalaya. They gave their own meaning and substance to the call for “system change” from a left feminist perspective.

In so doing, they contributed, among other things, to breaking the grip of fear (even if transiently) of reprisal and dismissal that has shackled workers for years from joining in protests; as well as facilitated new alliances between women leaders and male leaders within male-dominated trade unions, civil society organisations, and political parties. In the wake of the Aragalaya, some feminists have entered electoral politics to advance their struggles. The 2024 parliamentary elections also elected to parliament an unprecedented number of women from the Progressive Women’s Collective (PWC), the women’s wing of the National People’s Power (NPP), who identify as left feminists, some of whom were active in the Aragalaya. We contend that this is a unique moment in feminist politics in Sri Lanka.

This essay draws on a literature survey, our participant observations of the Aragalaya between April and August 2022, and over 15 interviews with a group of feminist activists who put their bodies on the line to engage with the Aragalaya on a sustained basis. In particular we draw on interviews with activists and leaders of organisations such as the Dabindu Collective, the Stand Up Movement, the Feminist Collective for Economic Justice, the Liberation Movement, and the Free Women. We understand the Aragalaya as a nationwide struggle that manifested in a number of different protest sites not limited to ‘Gota Go Gama’ (GGG) in Galle Face including in online and discursive spaces. We recognise that women were active in all these sites even if the focus of this paper is limited to a few sites. We also recognise that the Aragalaya whether at Galle Face or elsewhere did not represent all protests happening at the time nor all protesters (Kodikara 2022; Satkunanathan 2022). As Satkunanathan points out, contrary to statements that the Aragalaya is the longest peaceful protest in Sri Lanka, the non-violent struggle for truth and justice being waged by Tamil women family members of those who disappeared preceded the Aragalaya and continues to this day (2022: 555).

Centring women workers in the economy

Several women’s rights activists and organisations such as Dabindu Collective, Stand Up Movement and Liberation Movement played an active role in the Aragalaya from the very outset. Dabindu Collective not only joined the protests in Colombo but also assisted to organise protests in Katunayake, Ja-Ela, and Negombo. Chamila Thushari of Dabindu related to us how a group of them would come to Galle Face by about 10 p.m. at night, join the call-and-response chants, and take the 4 a.m. train back to Katunayake. In her view, workers from the free trade zones identified strongly with the Aragalaya—even though they could not participate on a daily basis to make their voices heard due to stringent rules around getting leave from garment factory work and the risk of losing one’s job, if workers skipped even a day of work. Yet many joined whenever they could and wherever they could. Workers joined protests held twice a week in Katunayake or demonstrations in Ja-Ela and Negombo at the end of their workday.

A large number of workers also joined the May Day rally during the Aragalaya which was held at Galle Face. And when trade unions announced an island-wide hartal on 6 May, almost the entire zone took to the streets in unison. According to Chamila Thushari, it was the first time in more than a decade that workers came out to protest fearlessly. She reminded us that the brutal repression of workers under the Rajapaksa regime and the killing of Roshen Chanaka, a free trade zone worker in 2011 had made workers scared of protesting about anything including their own rights. In the years after Roshen Chanaka’s killing, activists working near the zones have found it extremely challenging to mobilise workers.

Commemorating the killing of Roshen Chanaka, 1 June 2022.

Photo credit: Amalini de Sayrah

However, in Katunayake, on 6 May, nobody went to work. A group of activists including Chamila drew ropes across the entrances to zones around 5 a.m. on the morning of the 6th to urge workers to join the hartal. She says there were attempts to force workers to work, but in the end the activists prevailed, and they were able to hold a picket outside the zones. Later, many of the protesters made their way to Galle Face to continue protesting. There were still some repercussions for workers. In the days after the protest, the Criminal Investigation Department of the Sri Lanka Police came into factories to question workers. One worker was arrested and only released 20 days later, after more protests by activists such as Chamila.

Dabindu, Stand Up, and Liberation, also organised specific events on the rights of women workers, while critically analysing mainstream economic narratives from the standpoint of workers, within GGG in Galle Face and other Aragalaya sites. These included a press conference organised in the Media Centre tent at GGG, a teach-out at Independence Square, and a demonstration at Galle Face.

The press conference, organised by the Women-Led Bargaining Committee (WLBC – see below) together with the Liberation Movement at GGG on 26 April 2022, was on the theme of ‘Economic Restructuring: Working People at the Centre’. The event drew attention to women workers who have historically been—and remain—the backbone of the national and household economy, through plucking tea and tapping rubber; sewing ready-made-garments; and remittances from migrant domestic work. The women leaders stressed how the money “generated by their blood, sweat and tears” has been carelessly plundered and lost by the Rajapaksa brothers.

Press conference, women trade union activists, 26 April 2022.

Photo credit: Amalini de Sayrah

In a statement released after the press conference, the WLBC questioned the way the economy had been (mis)managed and highlighted the disproportionate impact of the crisis on women workers—particularly those in the free trade zones, many of whom they explained are increasingly Tamil migrant workers from the north and east. They demanded accountability from both national and international actors for the economic crisis and stressed the importance of protecting the livelihoods and human rights of working people. They also acknowledged the significant contribution of estate workers—predominantly Malaiyaha Tamil women—to Sri Lanka’s export earnings, noting that their economic rights, as well as those of women and minority communities more broadly, must be recognised, even though they are not represented in their unions. Swasthika Arulingam, president of the Commercial and Industrial Workers Union (CIWU) and a member of the WLBC, noted that the event presented some of the first open anti-International Monetary Fund commentary during the crisis, which was a marginal and unpopular position even among unions and certainly in wider society.

The activism around women workers’ struggles was also significant for other reasons. For decades, women-led trade unions in the apparel sector have been fighting two simultaneous challenges. First, the male domination of trade unions; and second, the corporate power of the industry that exploits the labour of women while obstructing their ability to organise, through harassment and strategic disciplinary action leading to termination of union branch leaders.

With regard to the first challenge, years before the Aragalaya, labour rights activists were having conversations about forming an alliance to ensure that their voices would be heard in collective bargaining processes and negotiations around the workers they represent.[3] The goal was to build a coalition capable of pushing back more effectively against corporate power. These discussions began to bear fruit during the Aragalaya, culminating in the formation of the Women’s Trade Union Centre and later the WLBC, both of which served to amplify women’s voices in relation to labour rights. On May Day 2022, women from these alliances were given an opportunity to speak at the trade union rally. Ashila Dandeniya of the Stand Up Movement stated that it was the first time that she had spoken before such a large audience in her decades of activism.

Ashila Dandeniya of the Stand Up Movement, May Day rally 2022.

Photo credit: Sakuna Gamage

With regard to the second challenge, the Aragalaya provided an opportunity to shift the discourse from an abstract focus on ‘dollars lost due to mismanagement’ and the people in power who had squandered public finances; to the working class—particularly women in apparel and plantation sectors and women migrant workers—who had earned those dollars in the first place. As Chamila Thushari noted, one of their key messages was: it is women’s work that generates economic profit for the country and it is women’s output that was drained from national reserves leading to the country having to default on servicing its sovereign debt in 2022.

The slogan that attempted to capture this reality that resounded in protests organised by workers during the Aragalaya was:

ඩොලර් හෙව්ව – කලාපයෙන්

ඩොලර් ගිල්ලෙ – සාටකයන්

Dollars we earned in factory zones

Dollars they squandered, the men wearing shawls.

As Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange reserves plummeted during the height of the economic crisis, the shortages in essential goods and price hikes decimated incomes of the working class. In forums and discussions on workers’ rights, unions repeatedly underscored the fact that it was the labour of the apparel workers that had sustained the country through the economic downturn that preceded the crisis—the COVID19 period. While most of the country ground to a halt, factories were marked “essential services” and continued to operate. This resulted in large clusters of ‘Corona’ cases within them, yet the industry still made profit off women’s labour. However, the consistency of support that activists such as Chamila Thushari had provided to workers during the pandemic meant they were speaking to a bigger audience when raising issues around the economic crisis.

This constituency remains important as they continue to address the twin challenges of women’s leadership within the trade union movement and the exploitation of workers. Yet every crisis brings fresh challenges. In the wake of Cyclone Ditwah, because migrant women workers are not registered as residents in the areas where they are employed, they are unable to access disaster relief (Fernando 2025); similarly to their exclusion from state support during the pandemic and the crisis.

Connecting national debt to household debt

On 23 April 2022, a group of women representing the National Movement of the Victims of Microfinance (NMVM) and their allies staged a march from near the Lake House roundabout to GGG in Galle Face to bring attention to the household debt crisis affecting millions of families across Sri Lanka. The 100 women and men gathered by Lake House had travelled by buses from different towns in the North Central Province. As the march began, they unfurled a long banner emblazoned with their rallying cry in Sinhala and Tamil.

“ගෙවන්නේ නෑ! ගෙවන්න බෑ! දුන් පොරොන්දු ඉටු කරුණු! ක්ෂුද්ර මුල්ය ණය වහා අහෝසි කරනු!”

“செலுத்த முடியாது! செலுத்தமாட்டோம்! கொடுத்த வாக்குறுதியை நிறைவேற்று! நுண்நிதி கடன்களை உடனடியாக இரத்து செய்!”

(Won’t pay, can’t pay. Fulfil your promises. Cancel all microfinance debts!)

Protest march organised by the NMVM, 23 April 2022.

Photo credit: Chulani Kodikara

Speaker, Hemamalie Abeyratne, NMVM protest march, 23 April 2022.

Photo credit: Amalini de Sayrah

The march which started around 2 p.m. culminated at a small makeshift podium beyond Gate Zero near GGG. Several women including Renuka Karunarathne from Welikanda representing NMVM and Nirosha Guruge and Hemamalie Abeyratne from Free Women, the women’s wing of the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), spoke to the protesters present. Renuka candidly admitted that many women victims of microcredit were among the 69 lakhs (6.9 million) who had voted to elect Gotabaya Rajapaksa at the 2019 presidential election. However, she stated that they were now joining the Aragalaya to send him home, and they would not go home until their loans were cancelled.

Nirosha Guruge, from Free Women spoke next:

Today we came to Galle Face as the victims of microfinance loans. In the country today, there are people who are living hand to mouth, who cannot afford to feed their families, cannot educate their children, and who are unable to go about their daily chores … Throughout the past few years, we waged struggles. We warned the government. Keep your promises. If not 29 lakhs [2.9 million] of victims of microcredit will come together with the Aragalaya protesters, and we will only look back when this government and this system is overthrown. As we said, we are here today, the victims of microcredit. Inside the homes, they are unable to cook. The price of rice has increased, there are no opportunities for self-employment, they don’t even have five cents in their hands. For these reasons, rural lives have been destroyed; some have been pushed to the streets. Thus, as women, as mothers, as sisters, we also came in solidarity to join this youth power (tharuna balayata javayak denna). From today, women will flock to Galle Face. The time when we hid our problems is over. We are telling this government, in the past, we said we are unable to pay this debt … We will not pay this debt. And we say it again – if you can take our debts, do it. We will not pay. We cannot pay. You have taken everything from us … Mr. Rajapaksa, get ready to go home. Are you not ashamed? […] The women in this country, the plantation workers, the women who are sweeping the streets, we are telling you to go home. Are you not ashamed to hide in your official residence?

We say it over and over again. We don’t want this. We are here as women to build a people’s power movement and a national government of farmers, workers, and students. We come in solidarity with the Aragalaya. That is our goal. Take your government and go. But first give us back every cent, every cent you stole from us. It is time to abolish the interest rates of microfinance companies. Thus, we say again and again, as the NMVM we will not pay this debt; we cannot pay this.

However, it is important to note that the slogan “ගෙවන්නේ නෑ, ගෙවන්න බෑ! செலுத்த முடியாது! செலுத்தமாட்டோம்! Won’t Pay, Can’t Pay!” first reverberated not at the Aragalaya, but from inside a small tent located in the Rajya Sabha Mandapa in Hingurakgoda in the Polonnaruwa district. The Hingurakgoda encampment was constructed on 9 March 2021 by a group of women farmers who came together as the National Movement of the Victims of Microfinance (NMVM) to organise a satyagraha against microfinance debt and high-profit companies (de Sayrah 2021). They were seeking to bring attention to the staggering number of families who every year fall prey to predatory microfinance companies functioning without any regulation in Sri Lanka.

The vast majority of these debtors are women, whether running a small business out of a living room in Colombo’s Kompannaveediya or a woman living and working on a tea estate in the Central Province. In February 2024, the Parliamentary Sectoral Oversight Committee on the Economic Crisis recognised that over 2.8 million people are affected by the microcredit crisis, and that over 2.4 million of them are women. Women are particularly vulnerable when it comes to microcredit because of inadequacy of incomes to look after families and their lack of access to credit on fairer terms through banks.

The NMVM satyagraha which started in March was discontinued on 1 May 2021 in light of the COVID19 regulations prohibiting gatherings (Wedagedara 2022). However, during the almost three months of the satyagraha, the women were joined by allies from farmer associations in nearby villages, trade unions and more women affected by microfinance debt from Katunayake, Vavuniya, Monaragala and Jaffna. The NMVM also found allies in and guidance from individuals who had participated in the farmer protests of 2015, bringing to the fore the cyclical and pervasive nature of the debt trap. The farmer protests of 2015 were in response to the rising rates of suicide in farmers who could not afford to feed their families due to a combination of drought and low rice prices, leaving them unable to pay back loans. Then too, the protestors had called for the cancellation of all the debt owed to state banks by struggling farmers. These continuities in relation to precarity highlight the way in which rural livelihoods that rely on agriculture and the environment still remain unsupported by the state and financial institutions.

The microcredit crisis highlighted by the NMVM satyagraha foreshadowed the national economic crisis that was on the horizon. As feminists have pointed out there is an intimate connection between national debt and household debt. A drive to repay sovereign debt reduces a government’s ability to mobilise resources for its people. Denied basic provisions, poor households are forced to take loans to survive periods of austerity and economic struggle. There are statistics and years’ worth of anecdotes to show that those taking small loans to keep families afloat are mostly women, preyed on by microfinance lenders—many illegitimate—at the borrowing and repaying stages. Mounting debt then compounds the struggle that women must face. Yet, consecutive governments have failed to provide a solution to this crisis.

In 2023, President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s proposal to establish a Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority (MCRA) came under heavy criticism of activists including the NMVM. The bill to establish the authority did nothing to address the socio-economic crisis created by microfinance lending and also eliminated the space for innovative and productive community lending (Wedagedara 2023). The bill was challenged in the Supreme Court, and the court held that several of its provisions violated the Constitution and must be passed with a special majority in parliament. The government eventually withdrew the bill.

The present NPP cabinet has gazetted a new version of this bill in November 2025, but it too fails to address the demands of those victimised by big microcredit lenders. The new bill recycles the thinking in the old one and misses “an incredible opportunity to learn from community practices to formulate a pro-people regulatory framework, strengthen community financing, protect the rights of credit consumers, and curb profit-driven lending”, according to activists Kumara, Gunawardena and Wedagedera (2025).

Economic justice from a feminist lens

The first visible manifestations of the 2022 economic crisis in Sri Lanka were the long queues forming outside petrol stations and gas stores and electricity cuts. What was not immediately visible was that, in a context of food shortages and rising prices, many people were already struggling to eat three meals a day and pay for medicine, education, and basic utilities. Children were dropping out of school.

In this context, amidst the inaction or resignation and even acquiescence to austerity economics of long-established progressive civil society organisations including some women’s groups, a number of individual feminist activists from across Sri Lanka came together as the Feminist Collective for Economic Justice (FCEJ) to understand and analyse the flailing Sri Lankan economy from a gendered perspective. They sought to show how women were disproportionately affected by the crisis based on lived realities and experiences, and demand that women be listened to in addressing the impacts of the crisis. In the first statement released by FCEJ in April 2022, they characterised the economic crisis as a humanitarian crisis.

Feminist activists have long argued that economic crises affect women disproportionately for a range of reasons. These include pre-existing gender inequalities, the division between productive and reproductive labour, the unequal burden of care borne by women, patriarchal social structures, and limited access to resources. Mainstream economic analyses ignore such knowledge. Many of the women who are part of FCEJ are not economists, yet they were determined not to be intimidated by so-called ‘experts’ into silence. In FCEJ member Niyanthini Kadirgamar’s view: “The task of crafting a people-centred economy cannot be relegated to the realm of local ‘experts’ or international ‘saviours’” (Kadirgamar 2022).

The group embarked on a collective learning process based on feminist curiosity. They sought facts and answers around what was unfolding in the country at the time. As they were educating themselves about big picture, macro-economic questions, they sought to link these to the everyday economics of poor and working people’s lives by asking another set of questions: who is, and how are they, paying this debt? What is the relationship between women’s labour and debt? Who brings in the foreign currency? Why are electricity prices going up? Why are there gas shortages?

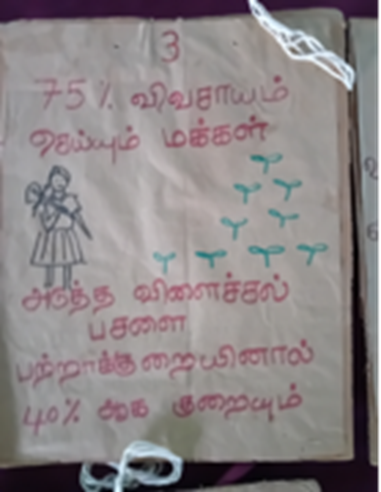

As they learnt, they were keen to share this knowledge within the communities with which they work. They started conducting teach-outs based on a set of 21 hand-made, hand-written, and illustrated cards. In simple language and with unambiguous drawings, these tackled different aspects of the economy. The original set of cards written in Tamil has since then been translated into Sinhala and English slide decks. The cards allowed the group to have these discussions anywhere, even under the shade of a tree. Indeed, the group did their first teach-out at Gandhi Park in Batticaloa on a Saturday evening as part of the Batticaloa Justice Walk (Emmanuel 2022).[4] They strung the cards on a string and tied it to one of the small trees in the middle of the park. From these teach-outs and interactions with communities, FCEJ learnt about how the crisis was impacting household economies in urban and rural areas. Their analysis, framings and statements are explicitly shaped by what they have understood. As Niyanthini Kadirgamar points out “Economists don’t connect with communities; they derive their conclusions based on abstract models. FCEJ on the other hand is able to construct a feminist analysis by speaking directly with women, mainly working-class women.”[5]

FCEJ teach-out, Gandhi Park, Batticaloa, 2022.

Photo credit: Feminist Collective for Economic Justice

Handmade cards on the economy by FCEJ.

Photo credit: Chulani Kodikara

Universal social protection has emerged as a priority for the group during and after the immediate crisis. Even prior to the crisis, Sarala Emmanuel, one of the members of FCEJ was thinking about the urgency of social security for areas such as Batticaloa, where people are still coping with the devastating human and economic costs of the war. As the economic crisis began to upend the lives of more and more people, FCEJ argued that universal social security measures could better cushion the most vulnerable sections of the population from the worst effects of the crisis. This thinking directly challenged the neoliberal consensus: that targeted social security could compensate for the deep impacts of austerity measures imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

FCEJ recognises that cash transfers can make a significant difference in poor people’s lives, provided they are meaningful amounts and conceived as a universal social protection scheme. However, the Collective broadens the frame of social protection to encompass citizenship, employment, and community-based entitlements flowing from the social contract between citizen and state. In their words: “social protection guarantees human dignity for all persons, recognizing that in life people may face circumstances that deprive them of their capacity to earn and fulfil basic needs” (FCEJ 2023: 3). The FCEJ contends that targeted social protection schemes based on assessments of poverty, as opposed to a universal approach, exclude people who ought to be covered. This is because the verification process to identify recipients tends to be coercive with excessive surveillance and data gathering, causes fear and fuels social disharmony, and generally fails the most marginalised persons. Targeting can also result in discrimination based on gender, humiliation, and invade the privacy of recipients (FCEJ 2023).

FCEJ is currently focusing their research and advocacy on Aswesuma: the social security scheme that replaced Samurdhi in 2023, on the pretext of implementing a better targeted scheme. They contend that Asweseuma is also riddled with inadequacies in its overall design—from the criteria used for selection, to the decision to begin phasing out the programme within just a few years. The FCEJ continues to advocate for a universal social security scheme. Increasingly FCEJ is learning from, and working in solidarity with, regional and global campaigns for debt justice and debt cancellation movements. Following the 2024 elections, the FCEJ studies the NPP government’s national budgets to understand whether there is a real shift from past economic policies; and whether budgetary allocations actually translate into resource commitments to advancing equality and justice for women.

From struggles against exploitation to critical analysis of the economy

For the feminist activists foregrounded in this article, the Aragalaya became more than a site of resistance against economic corruption, mismanagement, and authoritarian governance—or simply a battleground to “send one man home”. Instead, it evolved into a space from which to critique the economic exploitation of women and demand economic justice, fair representation in trade unions, and a restructuring of the capitalist system of accumulation and dispossession itself.

In making this claim we recognise that there is a long history of activism around women’s labour in Sri Lanka. Drawing on Kumari Jayawardena’s work on the history of labour, women’s struggles can be traced back to at least the 1920s. The categories of workers she identified as “the most exploited in Ceylon” remain so in the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka a century later: women workers on tea plantations, women classified as “unskilled labour” in factories, domestic workers, and peasant women. Writing in 1980, Jayawardena (2017: 251) observed an “awakening” among women workers regarding the nature of their exploitation. The 1980s indeed marked a period of heightened activism around labour rights, following the liberalisation of the economy and the establishment of free trade zones. Among the most notable struggles of that time was the successful strike by women workers at Polytex Garments, who won the right to trade union membership, higher wages, and a Christmas bonus. During this period, a coalition of women’s organisations formed the Women’s Action Committee (WAC) to support and express solidarity with the Polytex workers. The WAC sought to link women’s rights with broader democratic struggles, while also highlighting how deteriorating democracy threatened all ethnic communities and marginalised groups. However, Jayawardena noted, these struggles were not aimed at dismantling capitalism itself, but rather at confronting exploitation within it:

While it is true that the emancipation of women in Sri Lanka may not be achieved under conditions of capitalism, based as it is on the exploitation of the working people, nevertheless the awakening that is taking place among women about the nature of their exploitation is a necessary condition of their participation in the general struggle of men and women for liberation. (Jayawardena 2017: 251)

Jayawardena here does not refer to the Eksath Kantha Peramuna (EKP – United Women’s Front) which in a different era had challenged the capitalist structure of the economy—a point to which we will later return. Suffice to say here, that the activists that we foreground are confronting both women’s exploitation within capitalism and that socio-economic system. In the Aragalaya, they forged new alliances and collectives to do so. And in the wake of the Aragalaya, they are continuing their struggles with renewed energy in old and new spaces. Some have even entered representative politics in an attempt to undertake ‘system change’, through political parties and alliances, and from within elected institutions.

Engaging in party politics

Some of the women at the centre of this essay were already members of political parties and alliances such as the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, the NPP alliance and the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP) at the time the Aragalaya unfolded. Some went on to form new political parties. For instance, activists such as Arulingam, and Marisa de Silva, together with activists from the women’s wing of the FSP formed the People’s Struggle Alliance (PSA) bringing together a diverse group of activists, professionals, artists and three left political organisations—the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP), the New Democratic Marxist-Leninist Party (NDMLP), and the Socialist People’s Forum (SPF)—in a new alliance to represent working-class interests and challenge neo-liberal economic policies (Johnson 2024; People’s Struggle Alliance nd). It combines labour rights advocacy with broader social justice initiatives, while emphasising the intersection of class, ethnic and gender issues drawing on the diverse experiences of its leadership (Johnson 2024). Arulingam has explained the rationale for establishing the PSA as follows: “We want to be the opposition who supports the government when it passes laws and policies for the people and strongly opposes when the government acts abusively towards the people” (Johnson 2024; Arulingam and Fernando 2024).

The PSA contested the 2024 parliamentary elections from all the districts, but failed to gain a seat. Later in the May 2025 local government election it won 16 seats, mainly in pradeshiya sabhas (divisional councils), one of which was secured by a woman. The PSA has continued to raise issues at the margins of mainstream politics and challenge the new NPP government, which came to power on the wings of the people’s frustration and aspiration for change that found expression in the Aragalaya.

What is noteworthy here is that all-island elections held in 2024 and 2025 catapulted a group of left feminists into elected office in parliament and local government, some of whom were active in the Aragalaya. Of the 22 women elected to parliament following the 2024 elections, 20 are from the NPP. This number is unusually high and remarkable in and of itself; but that the women’s wing of the NPP, the PWC, is avowedly feminist, marks another unique moment in feminist politics in Sri Lanka. Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya who led the PWC, in an interview she gave to Lakmali Hemachandra (lawyer, trade unionist, and now an NPP parliamentarian) before the 2024 election, describes it as the culmination of conversations and debates that women had within the NPP/JVP about the need for a strong women’s movement with a left feminist perspective that shapes and influences the direction of the NPP and the need to mobilise women for that purpose (NEXT Sri Lanka 2024).

Kaushalya Ariyarathne, one of the new women MPs elected to parliament, in a recent piece in Polity provides further insight into the politics that shape the praxis of women who are part of the PWC. Speaking of the response of the PWC to the increase in the number of women elected to parliament at the 2024 parliamentary election, Ariyarathne states: “our consistent response emphasises that the parliamentary count represents only one facet of a broader, more complex struggle to enhance women’s political participation by left feminists” (our emphasis). Moreover, she goes on to state that the PWC grounds its work on two central pillars: unpaid care work and intersectionality:

By foregrounding care work, which is often invisible, undervalued, and predominantly carried out by women, we aimed to reimagine the economy around the principles of social reproduction, equity, and collective well-being … [Intersectionality] acknowledges that people experience oppression and privilege through multiple, overlapping identities—gender, class, ethnicity, sexuality, disability, and region, and thus pushes us to design strategies and policies of the NPP that address these interconnected realities. Together, these two principles ensure that our movement is not only rooted in critical analysis but also oriented toward transformative, inclusive, and equitable social change. (Ariyarathne 2025)

Do these statements signal an unsettling of the established boundaries between feminist politics, political parties, and the state, and how does the PWC hope to translate their left feminist orientation in terms of policy and practice? Are there possibilities of cooperation or an alliance between the left feminists outside—including women who are part of the PSA—and those within the state on a shared feminist agenda between the two? The evidence so far suggests that, despite the success of the PWC in mobilising women prior to the election, they have to ultimately act within the constraints of the NPP/JVP and a majoritarian parliamentary democracy. These dynamics are likely to generate dissension and disagreements between left feminists in and outside government and those supportive of the government and those independent or even critical of it.

It is difficult to predict the way in which the relationship between left feminists outside and inside the government will evolve in the coming years. Yet some divisions are already discernible as on the issue of regulating microcredit discussed above. A notable rift has also emerged with reference to Sri Lanka’s agreement with the IMF on restructuring Sri Lanka’s external debt. During the Aragalaya, many left feminist activists were united in their opposition to the IMF agreement. At the 2024 parliamentary elections, the NPP ran on a platform to renegotiate the terms of the debt restructuring programme to better protect vulnerable populations and ensure greater transparency and accountability. Yet, once in government, it has continued within the “straitjacket of the IMF” (Skanthakumar 2025); while some feminist activists have continued to call for its renegotiation. In the wake of the loss of lives and livelihoods and the massive destruction of property and infrastructure caused by Cyclone Ditwah, they are renewing their call to review this agreement. The FCEJ, for instance, has demanded that the government initiate urgent negotiations with the IMF and other creditors “to cancel debt repayment and reverse austerity policies in this crisis context” (FCEJ 2025).

These dissensions and dynamics recall an earlier era of left feminist activism in Sri Lanka with the formation of the Eksath Kantha Peramuna (EKP), described as one of the most “intriguing” left women’s organisations to emerge in Ceylon (de Mel and Muttetuwegama 1997). Formed in 1947 on the eve of independence from British colonial rule, the EKP was an alliance of diverse leftist women from the Sinhala, Tamil and Burgher communities. Some were members of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), others were from the Communist Party (CP). Some were married to left male leaders and others had no party affiliations. However, they all shared a commitment to a “Marxist economic model for independent Sri Lanka as the democratic way forward” (de Mel and Muttetuwegama 1997: 23). Even though, de Mel and Muttetuwegama say that the EKP’s “close adherence to the Marxist planned economy may seem naive, and its valorisation of women’s equality and labour rights in Soviet Russia rather overstated”, it proved to be:

a significant coalescing force in the Sri Lankan political life of the time. Its public interventions were always carefully argued, and its strategies for action multi-pronged as in the case of the jobs-for-women-in-the-public-service campaign. (1997: 25)

However, just over a year after its formation, it was disbanded. De Mel and Muttetuwegama attribute this to the failure of leftwing political parties to work together on a common agenda and the marginal position of women within their own parties. They go on to say that

ultimately this points to both the limited vision of these men in refusing to recognise the women’s agitation as a central plank in their own strategy, and the inability of the EKP women themselves to stand on their own feet and spearhead a movement not reliant on the nods of approval of their men. (1997: 25)

This history may uncannily rhyme with the predicament of left feminists at the present moment in time. Left parties, just as much as trade unions, have remained bastions of male domination. Even though the Aragalaya brought recognition and respect to several left feminist activists, the transition from street protests to party politics is likely to pose obstacles and challenges for these women—even if the battles that they are waging within their own political parties and alliances, whether the JVP and the NPP, or the FSP and the PSA, are not yet discernible to outside observers. There is no doubt, however, that the present political conjuncture presents another intriguing moment in the history of left feminist activism in Sri Lanka, which points to revival and resurgence as well as disagreements, dissensions, and discrimination.

A left feminist revival?

In this essay, we uncover and analyse a left feminist space of activism and mobilisation from the Aragalaya/Porattam/Struggle of 2022 to electoral politics. In 2020, Harini Amarasuriya was the only woman parliamentarian to identify as feminist and left. Since then, the PWC, led by her, has carved out a left feminist space within the NPP, with significant ramifications for women’s participation and representation in formal politics. The NPP victory in 2024, made possible by the Aragalaya, not only nearly doubled women’s representation in parliament from 5.3% to 9.8% but brought into that institution a group of women who identify as left feminist, or with left feminist aspirations. But the Aragalaya has also sparked a left feminist revival and engagement with electoral politics outside of the NPP. This is a watershed moment in politics.

It is too soon to parse the meaning of these developments for left feminist struggles—not only in relation to women, labour, and the economy, which have long been marginalised within national-level debates and discussions, but also in relation to broader struggles for ethnic justice and equality, queer rights, and ecological justice that left feminists have passionately fought for over the years.

The ability of left feminists within the NPP to realise their agenda will largely depend on the extent to which the NPP continues to see the PWC and its agenda as a central plank of its own manifesto and agenda. Meanwhile, those outside the NPP are continuing their struggles highlighted above (and many more), some in conversation and others in contestation with the NPP.

Chulani Kodikara is a director of the Social Scientists’ Association and an editor of Polity.

Amalini de Sayrah is a writer, photo-journalist, and activist.

Photo credit: Amalini de Sayrah

References

Anukuvi, Thavarasa. (2022). “Economic Crisis and Resistance in Batticaloa, Eastern Sri Lanka”. Polity, 10 (2): 23-30.

Ariyarathne, Kaushalya. (2025). “Gehenu Api Eka Mitata: Personal Reflections of Building a Women’s Political Movement in Sri Lanka”. Polity (4 November). Available at https://polity.lk/kaushalya-ariyarathne-gehenu-api-eka-mitata-building-a-womens-political-movement-in-sri-lanka/

Arulingam, Swasthika, and Marisa de Silva. (2023). “Women in the People’s Struggle”. LST Review, 31 (349): 52–55.

Arulingam, Swasthika, and Susitha Fernando. (2024). “Sri Lanka: ‘We must reclaim power from corrupted political and business elites’ – Swasthika Arulingam (PSA)”. Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières (9 November). Available at https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article72533

Balendra, Kimaya. (2025). Echoes of the Aragalaya: A multifaceted glimpse into the Sri Lankan protest movement. Colombo: International Centre for Ethnic Studies. Available at https://www.ices.lk/_files/ugd/fba0ea_bb32095cb3434b0e87f04df8062e2798.pdf

Centre for Policy Alternatives – Social Indicator. (2023). A Brief Analysis of the Aragalaya. Colombo: Centre for Policy Alternatives. Available at https://www.cpalanka.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/A-Brief-Analysis-of-the-Aragalaya_Final-Report.pdf

de Mel, Neloufer & Ramani Muttetuwegama. (1997). “Sisters in Arms: The Eksath Kantha Peramuna”. Pravada, 4 (10 & 11): 22-26.

De Sayrah, Amalini. (2021). “The bitter realities behind the Hingurakgoda satyagraha”. The Morning (2 April): https://www.themorning.lk/articles/127860

Emmanuel, Sarala. (2022). “The Batti Walk for Justice: A resistance for fundamental system change”. The Morning (31 July): https://www.themorning.lk/articles/212540

Feminist Collective for Economic Justice. (2023). “Social Protection for Sri Lanka: A Progressive Gender Sensitive Response to the Crisis”. Available at https://www.srilankafeministcollective.org/_files/ugd/06bf48_e91e38e5a22d47c2a3e3e1684201812c.pdf

Feminist Collective for Economic Justice. (2025). “End the Microfinance Menace! No to the new Bill!”. Polity (18 October). Available at https://polity.lk/fcej-end-the-microfinance-menace-no-to-the-new-bill/

Fernando, Ravishan. (2025). “රටට ඩොලර් උපයන වෙළද කලාපයේ කතුන්ට ගංවතුර සහනාධාරය අහිමි වෙලා [The women in the export processing zones who earn dollars for the country have been denied flood relief]”. මව්බිම [Mawbima] (16 December).

Jayasinghe, Pasan. (2022). “1/ of some thoughts from Colombo’s first-ever Pride March, held on June 25, 2022”. X (26 June). Available at .https://x.com/pasanghe/status/1540987002832621568

Jayawardena, Kumari. (2017). “The Participation of Women in the Social Reform, Political and Labour Movements in Sri Lanka” (1980). In Labour, Feminism and Ethnicity in Sri Lanka: Selected Essays (240-251). Colombo: Sailfish.

Johnson, Mark. (2024). “Voice of Change: Swasthika Arulingam and the Fight for Sri Lanka’s Future”. Europe Solidaire Sans Frontiere (10 November). Available at https://europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article72548

Kadirgamar, Niyanthini. (2022). “Economic crises, IMF and women’s labour”. The Morning (22 May): https://www.themorning.lk/articles/203845

Kodikara, Chulani. (2022). “Ghosts”. In Krishantha Fedricks, Farzana Haniffa, Anushka Kahandagamage, Chulani Kodikara, Kaushalya Kumarasinghe, and Jonathan Spencer, “Snapshots from the struggle, Sri Lanka April–May 2022”. Anthropology Now, 14 (1-2): 21-38.

Kumara, Suneth Aruna, Renuka Gunawardena, and Amali Wedagedara. (2025). “Then as farce, now as tragedy: The second coming of Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority”. Daily FT (10 December): https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Then-as-farce-now-as-tragedy-The-second-coming-of-Microfinance-and-Credit-Regulatory-Authority/14-785465

Kumarasinghe, Kaushalya, (2025). Aragalaya: A Journey in Progress. Colombo: Law & Society Trust. Available at https://lst.lk/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Aragalaya-A-Journey-in-Progress-Online-Book_English.pdf

NEXT Sri Lanka. (2024). “‘ගැහැනු අපි එක මිටට’ ඇයි? සමුළුවලින් පස්සෙ මොකද වෙන්නෙ? [“Why ‘Women, we are one’? What happens after the conferences?]”. YouTube (8 February). Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DFLICsaF4-g

Perera, Ruhanie. (2023). “Embodied Witnessing: Performance Expressions as Acts of Citizenship within the Sri Lankan Context”. Samaj: South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 31.

People’s Struggle Alliance (nd). “Who we are”. People’s Struggle Alliance. Available at http://psalliance.lk/

Rambukwella, Harshana. (2024). “The Cultural Life of Democracy: Notes on Popular Sovereignty, Culture and Arts in Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya”. South Asian Review, 46 (1 & 2): 11-26.

Satkunanathan, Ambika. (2022). “What Do Women Have to Do With It?: The Multi-Dimensional Nature of the Sri Lankan Crisis”. Feminist Studies, 48 (2): 547-556.

Skanthakumar, B. (2025). “Budget 2025: Playing A Bad Hand”. Polity, 13 (1): 91-101.

Talcott, Mary and Dana Collins. (2012). “Building a Complex and Emancipatory Unity: Documenting Decolonial Feminist Interventions Within the Occupy Movement”. Feminist Studies, 38 (2): 485-506.

Wedagedara, Amali. (2022). “Debt, development and the future”. The Morning (5 March): https://www.themorning.lk/articles/192182

Wedagedara, Amali. (2023). “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority: Recipe for disaster”. The Sunday Times (31 December): https://www.sundaytimes.lk/231231/business-times/microfinance-and-credit-regulatory-authority-recipe-for-disaster-541150.html

Notes

[1] The gruel of rice, water, and salt which had sustained families trapped without sufficient food and physical security between the Sri Lankan military and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in the final days of the war.

[2] Acknowledgements: Our sincere thanks to the feminist activists who shared their experiences of the Aragalaya with us. Tavishi Arunathilake transcribed several interviews, which is much appreciated. B. Skanthakumar and Rebecca Surenthiraraj provided helpful feedback on earlier drafts and edited the final version for publication. We are grateful to the Roxa Luxemburg Stiftung (RLS) New Delhi office for their support of the research with funds from the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of Germany. The opinions and views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the RLS.

[3] The Asia Floor Wage Alliance (an INGO) played a role in this initiative to bridge divisions between workers organisations and women-led trade unions, for the purpose of challenging the male dominance of trade union platforms. The WLBC has since been inactive following conflicting attitudes of its former constituents towards the NPP government.

[4] The Batticaloa Justice Walk began in parallel to the protests at GGG (Emmanuel 2022; Anukuvi 2022). The walk continues at time of writing. The FCEJ members who form its core participants engage the community in discussion and song to create fellowship and awareness. They have broadened the calls of the first protests to now encompass matters that are local to the area—post-war relationships between communities, gendered violence and natural resource exploitation. These teach-outs also provided an opportunity to share strategies to alleviate the worst effects of the crisis whether by sharing resources or starting community kitchens.

[5] Conversation with Niyanthini Kadirgamar, 30 September 2025.

You May Also Like…

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...

Gananath: Renaissance Man

R. L. Stirrat

I met Gananath in July 1969 on the day I first arrived in Sri Lanka, Edmund Leach and Stanley Tambiah having imposed...