Words to Kill a Man, and Free a Man

Kanya D’Almeida

In the early months of 2012, I inherited two troves of literature. I had been hunting for one of them for years; the other arrived unsolicited.

The first was an archive of the journalistic work of my uncle, Richard de Zoysa, during his career—cut short by his murder in 1990—as a reporter for the Rome-based Inter Press Service (IPS) news agency.

The second was the unbound, unedited manuscript of an American political prisoner, a former Black Panther named Russell ‘Maroon’ Shoatz who had been incarcerated in the state of Pennsylvania for nearly four decades.

I was a news reporter myself at the time, employed by the same agency that Richard had been working for when he was killed. I had recently been transplanted from New York City to a desk at IPS’ Washington office, where my bureau chief, an exceptionally sharp, veteran journalist—whose small room on the 14th floor of the National Press Club in DC was primarily occupied by heavy metal filing cabinets jammed with news cuttings and clippings from decades past— kindly allowed me to conscript him into my search for Richard’s dossier.

All my life, Richard had twirled above me like a mobile over a baby’s crib: shifting, wonderful, shadow-casting, and always out of reach. He and my mother, first cousins, had been raised as siblings in the same home. She had witnessed, perhaps more intimately than anyone else, his evolution from a precocious child (whose mind may have bordered on genius) to a kind of cultural titan in Colombo, his presence dominating the stage, his voice crackling through radio broadcasts, his face on television screens reading the evening news—and finally, his byline on the international wire, in dispatches from Sri Lanka.

I had read his poetry and paged through dozens of photo albums documenting his acting career (which began with a very professional adaptation and home production of Hamlet’s soliloquy To Be or Not to Be when he was nine years old) and I had heard stories about stories about stories—but never actually read his journalistic work.

All these articles, I would ask my parents, his colleagues, the Internet—that he was threatened for, followed for, murdered for—where are they?

Gone? Lost? Scrubbed out?

It was with my excellent bureau chief, both of us huddled over his archaic desktop computer one afternoon, that we managed to extract, from the depths of JSTOR, one of Richard’s pieces entitled ‘Pride Stalks Beneath a Full Moon’. The dateline read “COLOMBO, May 22, 1989”. It was locked behind security passwords and paywalls. While my boss made stern phone calls to the relevant, automated authorities of that impenetrable digital library, I hurled abuse at the screen that kept telling me I lacked the required credentials to access my uncle’s writings.

What we ultimately ended up with—a small cache of articles constructed in the signature IPS style of an inverted pyramid with a buried lede and delivered in Richard’s sparse yet polished prose—felt to me like finding the missing shard in a fragmented family heirloom.

*

A few weeks later (or was it a few weeks earlier?), I received a FedEx envelope containing a 200-page document titled, The Making of a Political Prisoner by Russell Maroon Shoatz. An accompanying note from a recent acquaintance said only that he wished me to review the draft of this autobiography with a view to using it as the basis for a screenplay. The man whose life story was contained in that bulky envelope, my friend explained, was nothing short of jaw-dropping—he’d escaped prison twice in the 1970s, spent over 22 years in solitary confinement, and was a prolific revolutionary theoretician and scholar, revered by The Movement and despised by the authorities who had sworn to preside over his slow death in the Hole. The Hole. Shorthand among prisoners and guards for solitary confinement.

The name ‘Maroon’ was an honorific, a respectful reference to the many thousands of slaves who, on almost every continent, escaped the plantations, formed liberated communities, and lived as free people. His supporters and some of his family believed that a powerful biopic would help to ignite an international campaign for his freedom bid. After all, everyone loves a good story. It would require a significant commitment on my part: to interview Maroon himself, which was complicated by his status as a maximum-security prisoner; and to meet and speak with his tribe—children, comrades, counsel, co-defendants.

I was fresh and green—25 years old, with a ready pen, steeped in American cultural mythology (particularly such vague notions as freedom of speech, or the power of the people, organised and united)—and hungry for meaningful work as a writer.

I was also afraid. The twin revelations of Richard’s past and Maroon’s imagined future—with myself strung between—felt somehow double-edged: the sweet promise that words might be powerful enough to free a man were dogged by the horror that words were dangerous enough to kill a man.

Both men were stunning writers, in very different ways. Maroon’s chapters read like spoken word, a beautiful language of the streets fine-tuned in the depths of isolation. He grew up in a gang in West Philadelphia, became a community organiser, joined the Panther Party, and stood trial for murder before spending most of his adult life in prison. But his story had no ending, whereas Richard’s seemed to begin at the end—with his own death—and then plough its way painfully backward in time through a dismal chapter of Sri Lanka’s history.

*

All of Richard’s articles I unearthed were published roughly in the first half of 1989 and ceased abruptly on 10 August with the publication of a piece entitled, ‘SRI LANKA: Nearing a Human Rights Apocalypse’. Still, after thirteen years and dozens of reads, the prophetic flavour of that pithy 899-word bulletin sends chills down my spine. The opening paragraphs need little explanation:

Residents of the seaside suburb of Mount Lavinia, three miles from the Sri Lankan capital of Colombo, were awakened at around 3:00 AM on Aug. 6 by gunshots.

As the night curfew in force throughout Sri Lanka ended one hour later, the bolder ones ventured out of doors. They found the bodies of six youths – five dead, one dying of gunshot injuries – their hands tied behind their backs, lying on the beach.

The injured boy told them he was from Ganemulla, a small town 25 miles from the capital. Mount Lavinia residents say he accused the Special Task Force (STF) – police commandos – of dragging him from his house, bringing him to Colombo and shooting him.

Killings like this happen daily in southern Sri Lanka, where the security forces are hunting down left-wing rebels from the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in a major government drive to wipe out what it calls “subversion”.

This, in a nutshell, was Richard’s beat: piecing together, victim by victim, corpse by corpse, the story of the violent insurgency and still-more-violent counter-insurgency that throttled Sri Lanka in the late 80s. And it wasn’t the first time—the piece took its title from remarks delivered in Parliament on 9 August 1989 by the then-opposition leader Sirimavo Bandaranaike, demanding the creation of a parliamentary committee to look into arrests and indiscriminate killings, which had topped 1,000 just that month:

Bandaranaike, who crushed a JVP-led student insurrection when she was prime minister in 1971, yesterday chose to make a distinction between the JVP and the youth who support it in her apocalyptic statement in Parliament.

“These are our future generations. Why have they resorted to violence? Because they have no education — schools and universities are closed, they have no hope of employment, they see injustice and corruption all around them, she declared.

“If you have no answer except to meet indiscriminate killings with equally brutal reprisals . . . You will build up a monster no-one will be able to control”, Bandaranaike warned.

The article goes on to detail the particular horrors of that time, namely the lawlessness that rendered the entire population either victim or suspect, and the rest terrorised into silence:

Masked men travelling in vehicles without license plates were abducting young men from their homes. Human rights activists say most of the “secret” killings are carried out by plainclothes squads from the regular forces. The government closed down schools in Sinhalese areas in June and followed up by sending the military onto southern campuses July 11.

Members of the campus group “Students for Human Rights” say the 250 students taken into custody were the lucky ones.

“Most of those arrested on campus are still alive, although in detention”, says “Kumar”, a spokesperson for the group. “It is when the students go back to their homes that they are in the greatest danger. The local police or military come for them with a license to kill.”

The “tire treatment” is a common form of punishment meted out to suspected rebels. Villagers and townspeople alike have grown used to the sight of bodies smouldering on public roadways, charred flesh indistinguishable from burning rubber.

Other suspects were blindfolded, tied to trees or lampposts, and shot – often after being tortured.

Under Sri Lanka’s harsh emergency regulations and anti-subversion laws, police or military officers can dispose of dead bodies without autopsies and detain anyone for up to 18 months without producing them in court.

“We have filed hundreds of habeas corpus applications (calling on police to produce arrested people before magistrates) but under the law, the government need not do anything about these”, explained human rights lawyer Prins Gunesekera.

Gunesekera says he himself is in danger. He and another lawyer, Kanchana Abeypala, have been placed on an “endangered” list by the human rights organisation Amnesty International after they were warned to stop campaigning against rights abuses.

A third lawyer from the human rights lobby, Charitha Lankapura, was murdered – allegedly by the STF – in early July after returning home from a student demonstration.

Surely, no clearer prologue to his own death could have been written: abducted from his home without charge or warrant, shot, and his body dumped in the sea. No investigation, no explanations. For decades I have listened to my elders talk in circles of speculation as to the causes and culprits behind Richard’s murder—Why? On whose orders? For what?—without ever arriving at an undivided answer.

*

It is tempting to surmise that Richard’s clarity of analysis and reporting were reason enough for the government to remove him. In a dispatch from 22 May 1989, Richard notes:

Pride stalks Sri Lanka today, in a variety of guises. There is the racial pride of the Sinhalese, who make up 70 percent of the island’s 17 million people (mostly Buddhist), as well as the pride of the 1.4 million-strong Tamil minority.

There is also the pride of two fierce militant groups, one Sinhalese and one Tamil; the pride of two armies, one Sri Lankan and one Indian; and the political pride of their governments in Colombo and New Delhi.

He goes on to detail the political manoeuvres required to juggle multiple conflicts, with the government funnelling its armed forces into the “economically underprivileged southern belt” to root out the JVP while simultaneously directing a stream of soldiers to the Northern Province to wage war against the LTTE. All this, Richard notes, while the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF), by order of Rajiv Gandhi, were half-cajoling, half-strong-arming the Tigers to a negotiating table, upon which lay the highly divisive devolution plan outlined in the 1987 Indo-Lanka accords.

“The JVP and the shadowy organisation suspected of being its armed wing (known as the Patriotic People’s Movement or DJV) [are] implacably opposed to Tamil separatism or anything remotely approaching it”, he wrote, adding that on the flip side of the coin, the LTTE remained hell-bent on the creation of a wholly separate Tamil homeland, despite a strong political tide amongst more moderate Tamil forces that would have accepted an agreement for regional autonomy. Richard concluded:

A triangle of power [now governs the country]. If [President Ranasinghe] Premadasa, a shrewd self-taught professional politician, wants his presidency to get off the ground, he will have to deal swiftly with two men who, like him, have simple origins – Tamil Tiger guerilla leader Velupillai Prabhakaran and JVP supremo Rohana Wijeweera.

The actions of this trio will determine Sri Lanka’s immediate future – as well as the fate, in life or death terms, of the country’s 16.4 million people.

It was the kind of journalism I aspired to: clean, clear, concise, and contextual, with a beating heart that seemed able to keep time with the louder pulse of the nation. Nothing seditious or revolutionary. No call to arms. Nothing but a writer’s quiet plea for sanity or humanity to prevail amidst a massacre. It was not, to my mind, the kind of blazing scroll that an artist might—even for the faintest moment—think they’d die for.

The unasked question being, of course, Was it worth it, in the end? These dispatches from Sri Lanka, written in a time of terror, delivered to an international audience that could do nothing to stop the bloodshed—was it worth it? How, really, do you value a human life against the value of his or her work?

Such was the diabolic arithmetic I was being forced to work out in real time as a small team of freedom fighters working on behalf of Russell Maroon Shoatz pressed me for an answer on the proposed assignment of working with a complete stranger to tell his life’s story. I read and reread Richard’s articles, and read and reread Maroon’s letters, which had begun to arrive in my mailbox on Georgia Avenue NW Washington, DC. I observed the words of both men fusing together in unnerving ways. Notions of duty, legacy, and artistic responsibility jostled in my mind with a dull, pervasive anxiety at the prospect of committing myself to a literary work with the highest possible stakes: another person’s life and freedom, and—if I was to follow the mad logic that resulted in Richard’s murder—possibly my own.

“Let’s say I write this book, with a high-security prisoner who’s accused of murder and who calls himself a prisoner of war,” I said to my father, trying to laugh off my deepest fears. “What’s the worst they can do to me? What’s the worst that could happen?”

To which he answered, quietly and without pause, “Deportation. Incarceration. Torture.”

I grieved that response for a long time, perhaps because it was the first time I had truly confronted the fear that the survivors of Sri Lanka’s violence—my own family, myself—carry with them, in their bones. I grieved also for these two men, one who had been killed, and the other who’d been sentenced to a different kind of death, which in the twisted parlance of the American justice system is known as Life. Maroon was serving back-to-back life sentences in solitary confinement. His letters to me were composed in the laboured hand of an old man with a youthful spirit who has been made to stare into the black abyss and see right through it, to the beauty and the hope.

I shared some of Richard’s work with Maroon, and told him, briefly, the story. He wrote back at once, soulful and wise: When we speak truth to power… When we speak truth to power… When we speak truth to power. It was, in a way, an answer to the question I had not asked, that my family have prowled around all my life, that Maroon had, I later learned, been avoiding and confronting for decades in the screaming quietude of a cage measuring five by seven feet: Was it worth it, in the end?

A year later I met Maroon in person, down in the dungeon of the State Penitentiary at Mahanoy, an all-male prison in rural Pennsylvania, in a visiting room bisected by a sheet of bulletproof glass. Throughout the visit Maroon remained shackled at the ankles and at the wrists, a bright-eyed, ageing, and agile man with whom I would collaborate for 12 years on his autobiography I Am Maroon. He did not live to see its release. It was published, posthumously, on 3 September 2024, nearly three years after Maroon died of cancer.

People often ask my family how we make sense of Richard’s life and death. It was not until I met Maroon and undertook a kind of doctoral degree in American studies under his tutelage, with his supporters acting as my academic advisors and the prisons of Pennsylvania serving as my campus, that I began to understand how legacies work: they must be allowed to live. Nothing finishes a person quite like memorialising them; nostalgia and romanticising will make quick work of whatever is left. Maroon did not suffer from nostalgia—probably because, I always assumed, it’s a deadly disease for a prisoner serving a life sentence. He was a great believer in living legacies. He mentored countless young men who were thrown into the penitentiary alongside him and saw many of them off into the free world while he continued to Do His Time. Dozens have said they regard him as a father-figure, as their greatest teacher.

As for me, writing together with Maroon, through the bars and over all the hurdles thrown at us—visits cancelled and monitored, our correspondence surveilled, letters destroyed or returned to the sender, threats and lawsuits—seemed like the most sensible way to honour Richard’s legacy in my own lifetime. Mainly because it helped me to do away with that blasted question: Was it worth it, in the end?

Turns out it’s not a question at all, but a slow reckoning with language itself, with these words that are strong enough to kill a man, and free a man. And what emerges from that reckoning is not doubt or unknowing, but a certain certainty, that you have to use words to make sense of them. You have to let them play, let them remake themselves: We are worth more than the ends they devise for us. We live, and live on, because we are worthy of life.

Kanya D’Almeida is a writer, and winner of the 2021 Commonwealth Short Story Prize. She is the co-author of I Am Maroon: The True Story of an American Political Prisoner, available now from Hachette Books.

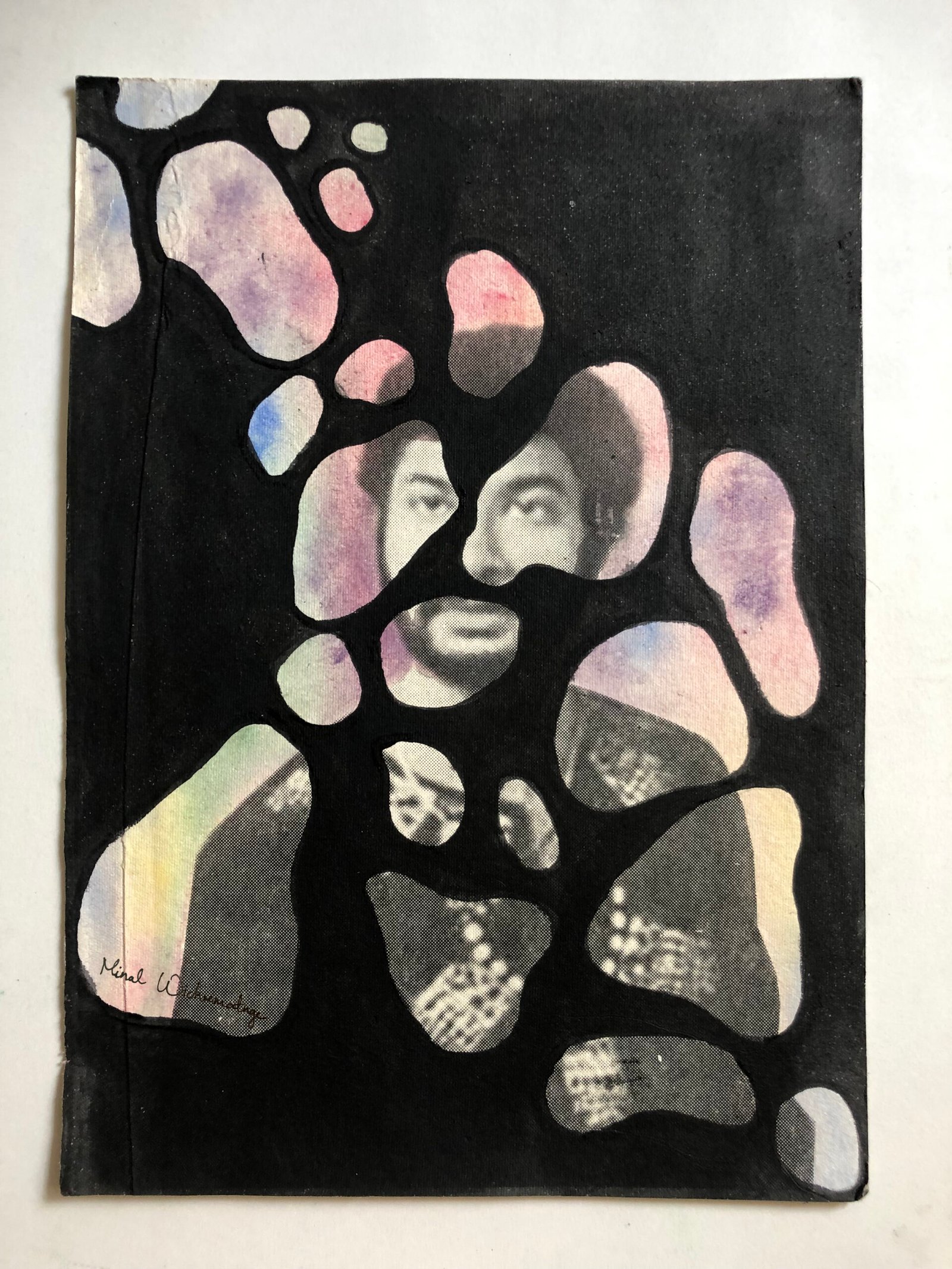

Image credit: Minal Wickrematunge

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...