The Empathic Sinhala Short Story: Gahaniyak by Martin Wickramasinghe

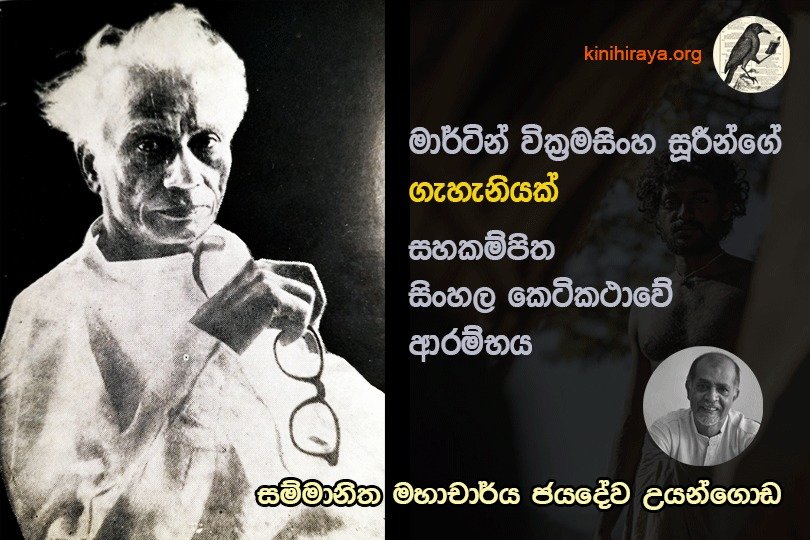

Jayadeva Uyangoda

In participating in this celebration to mark the centenary of the publication of Martin Wickramasinghe’s short story collection Gahaniyak (‘A Woman’) my aim is to highlight a few aspects of his contribution as a short story writer as well as a literary and art critic.[1] In my view, to adequately evaluate and critique Wickramasinghe’s novels and short stories, we need to connect that effort with fresh reflections on his worldview which is easily found in his works of literature as well as art and social criticism.

One feature that distinguishes Wickramasinghe from other Sri Lankan short story writers and novelists is his simultaneous engagement, alongside his creative work, in literary, artistic, and social criticism, yet with the same degree of creative capacity and commitment. For an autodidact with no background in formal higher education or academic training, the body of work he produced over six decades of a literary career in creative writing, and literary, social, and cultural critique, is astonishingly original and substantial. Wickramasinghe, while being a prolific novelist and short-story writer, has also been a dissident cultural practitioner and cultural theorist who interrogated the established traditions and orthodoxies of both creativity and criticism. In all of Wickramasinghe’s fictional work, readers can trace the presence of a unique worldview, both implicitly and directly, also revealing the various stages of its development, from highhanded moralising to sophisticated social commentary.

In this essay, I will try to outline the basic dimensions of Wickramasinghe’s worldview which has a remarkable continuity encompassing most of his writings – fiction and non-fiction alike. It is in the collection of short stories Gahaniyak, published in 1924, that Wickramasinghe first articulated in rather subtle ways a personal philosophy or worldview, which was to remain with him faithfully until his last novel, Bavatharanaya, published in January 1973.

A Cultural Theorist

From Martin Wickramasinghe’s oeuvre, we can identify two key dimensions of his work as a whole. Firstly, Wickramasinghe was not only a creative writer and literary critic. He was also a cultural theorist in a somewhat broader frame with original and secular insights into Sri Lanka’s Sinhala Buddhist culture. The term ‘cultural theorist’ is not often used in our country. Ananda Coomaraswamy, a Sri Lankan-born scholar who initially worked in Sri Lanka before residing and working in the United States, could be regarded as Sri Lanka’s first modern cultural theorist. After Coomaraswamy relocated himself outside South Asia, Martin Wickramasinghe emerged as the major cultural theorist in Sri Lanka. A cultural theorist is not solely a literary or cultural critic, but rather someone who interprets and makes sense anew of works of art and literature through fresh studies of their historical, social, religious, philosophical, and sometimes political contexts as well as backgrounds, influences, and limitations. In so doing, cultural theorists would be self-conscious about the interpretative principles and assumptions that shape their specific judgements and evaluations. In the subsequent parts of my essay, this argument about the vocation of cultural theorists will be briefly elaborated with reference to a few of Wickramasinghe’s short stories, novels, and critical cultural writings.

My initial point regarding both Coomaraswamy and Wickramasinghe is that they have been pioneering interpreters of South Asian culture. There has been a significant divergence between their bodies of work in terms of the readership and receiving constituencies. Coomaraswamy interpreted Asian Hindu, Buddhist and folk art and culture primarily for Western academic communities. Wickramasinghe interpreted South Asian Buddhist culture for Sinhala-reading intellectual communities in Sri Lanka. Coomaraswamy engaged with the cultural intelligentsia of the Western world to persuade them to appreciate the religious-spiritual roots of Asian art and aesthetics. The book, The Dance of Shiva: Fourteen Indian Essays, published in 1918 in New York, is a major text by Coomaraswamy of this interpretative genre. Wickramasinghe in contrast directed his attention to his own society, interpreting Sinhala Buddhist art, literature, and culture from a secularist interpretative framework. It is important to note, even in passing, that Wickramasinghe may have been a cultural nationalist, but certainly not in an ethno-nationalist or communalist mode, as some of his latter-day followers of the Jathika Chinthanaya school of Sinhala nationalism would see him.

When reading the works of these two interpreters of culture, it becomes apparent that they approached cultural colonialism in distinctly different ways. Coomaraswamy’s aim was to show the spiritual, civilisational, and aesthetic authenticity of Asian fine art to the Western and Christian world. On the other hand, Wickramasinghe attempted to explain to the Sinhala-educated intellectual communities of Sri Lanka, the ordinary and subaltern social origins of the aesthetic excellence achieved within the practices and traditions of Sri Lanka’s Sinhala Buddhist art and literature. In Wickramasinghe’s radically new interpretative work, the recognition of what is authentic in the Sinhalese, or what is pristinely Buddhist in Sri Lankan culture, is not a matter of ethno-cultural labelling. Rather, it should be an acknowledgement of the fact that the authenticity of what is understood as the Sinhala Buddhist art and culture in Sri Lanka is primarily social; and that it has been rooted in a peasant, subaltern (podu jana), and counter-elitist aesthetic of resistance. As Wickramasinghe suggests repeatedly in his non-fiction works, the cultural impulses for that resistance came from a fusion of the non-atmavada (i.e. rejection of the doctrine of an eternal soul) ontology of the Buddha’s emancipatory teachings and the social ontology of passive resistance among the peasant communities.

Wickramasinghe also developed a critique of Coomaraswamy. It contains a few elements of Wickramasinghe’s materialist worldview. In his Sinhala Lakuna (‘Identity-Marker of the Sinhalese’), first published in 1947, Wickramasinghe had a rather sharp response to Coomaraswamy’s interpretation of India’s Hindu art. Wickramasinghe suggested that Coomaraswamy’s well-known work The Dance of Shiva was a mere apology for the Hindu atmavadee (doctrine of self or soul) art. That is, an apology constructed by romanticising the occult beliefs and mystified tales about the deities worshipped among the primitive early Indian communities and later popularised by the brahmin priests (Wickramasinghe, 2019: 12-14).

Wickramasinghe’s critique of Coomaraswamy’s work has three more crucial points. First, Wickramasinghe firmly rejects Coomaraswamy’s acceptance of the Hindu caste system’s legitimacy as defined by the brahmin elites. Wickramasinghe points out that Coomaraswamy was among the Eastern and European scholars who “argued that the caste system was essential to maintaining the continuity, stability and welfare of the society as well as the nation”. Second, Wickramasinghe asserts that Coomaraswamy’s romanticisation of Indian culture was a wrong response to the devaluation of ancient Indian culture by scholars who wanted to demonstrate the superiority of Western culture. It merely led scholars like Coomaraswamy to exaggerate the value of the very ordinary aspects of Eastern culture as spectacular creations of the ancient sages. Third, in Wickramasinghe’s view, Coomaraswamy’s claim that Eastern culture was spiritually superior to Western culture reflects only a deeply felt, yet unwarranted sense of inferiority (Wickramasinghe, 1947: 87-88).

Similarly, the colonialism that Wickramasinghe criticised and attacked was not one of European origins. Rather, it was the colonising intellectual, cultural, and aesthetic domination stemming from India’s brahmin and Sanskrit intellectual elites. According to Wickramasinghe’s dissident thesis of the fall and rise of classical Sinhala literature, this dominance of the brahminic and Sanskritic elites prevailed in Sri Lanka since the ninth century. It had even caused a rapid impoverishment of the aesthetic authenticity and autonomy of the arts and culture of Sinhala Buddhist society. The resurgence of its aesthetic autonomy and authenticity has been the achievement of artists and writers of peasant social-cultural roots and podu jana sensibilities.

Wickramasinghe’s dissident thesis is developed notably in Sinhala Sahithyaye Nageema (‘Rise of the Sinhala Literature’, first published in 1945); Vichara Lipi (‘Essays in Literary Criticism’, first published in 1945); Sinhala Lakuna; Kalunika Seveema (‘In Search of the Magical Herb’, first published in 1951); and Sinhala Vichara Maga (‘Path of Sinhalese Literary Criticism’, first published in 1964).

The clearest statement of Wickramasinghe’s thesis on the nexus between the non-atmavada ontology of Buddha’s teachings and ‘common people’s culture’ is available in the preface to his Sinhala Vichara Maga. Wickramasinghe’s main argument is that there is a fundamental ontological distinction between the Hindu brahminic and Buddhist conceptions of culture and art. It is based on the atmavada (the doctrine of an eternal soul) of Hinduism and the anatmavada (denial of the presence of a soul) of Buddhism. Thus, Hindu and Buddhist cultural principles have been fundamentally different from each other because they evolved into two incompatible ontological and religious frameworks. Meanwhile, the principles of Sanskrit aesthetics are connected to the doctrines of atmavada-based cosmological doctrines of fantasy and super-natural divine beings and their human manifestations. In contrast, the principles of Buddhist literature are connected to a worldview of human-centric realism rooted in the philosophy of anatmavada, which does not accommodate a belief in an eternal soul with human and divine manifestations. While the Sanskrit poetry and the aesthetic theories, or poetics, of alankaravada and rasavada are mystified representations of the Hindu atmavada beliefs among the brahmin elites, the old Buddhist Pali poetry reflects the non-mystified teachings of an anatmavada school of humanist realism. While the former has produced an extravagant aesthetic of divine experience and the pretentious lives of the kings, the latter is specific in its production of a simple aesthetic of the human experience of ordinary men and women. Thus, Wickramasinghe’s aim was to make a case for secularised poetics as an alternative to alankarawada and rasavada traditions of the Sanskrit brahminic aesthetics.

Wickramasinghe goes on to argue that Buddhist literature, in terms of doctrinal teachings and principles that guided it, comes close to the 18th-century English fiction shaped by European philosophies of realism. The Buddhist approach of realism rooted in anatmavada is reflected in the Buddha’s rejection of atmavada as well as the Vedic doctrinal dogmas. The Buddha also rejected Sanskrit as the choice of the language of communication in preference to Prakrit which was a language of the common people (podujana basak) to convey his teachings. That enabled the Buddha to use idioms, expressions, images, and metaphors from the lives and culture of ordinary people, instead of the highly stylised language and linguistic expressions of the Sanskrit poets. Wickramasinghe makes the imaginative claim that this realistic approach, or ‘ontological realism’, had two important consequences for Buddhist culture and literature. First is the emergence of a ‘Buddhist realist’ aesthetics that did not attempt to provoke human emotions as in the rasavada traditions of the Sanskrit elitist literary culture. Rather, its commitment was to cultivate a capacity for rational reflection through restrained emotions. The second is the promotion of ‘faith in the human beings in their ordinary lives’ (manawa bhakthiya), rather than of gods and deities living in a cosmos of fantasy (deva bhakthiya) (Wickramasinghe, 2015: vii-viii).

Recognition of such specific aspects of Martin Wickramasinghe’s cultural interpretivist project sheds some useful light on how he has built an outline of a social, and therefore secular, aesthetic in his novels and short stories.Top of Form It is indeed long overdue to acknowledge the importance of the pioneering work undertaken by Wickramasinghe, the cultural theorist, in proposing a new approach and framework for understanding the culture, art, and literature of Sinhala Buddhist society. One way to term this approach employed by Wickramasinghe is to call it the ‘hermeneutic of defiance’. Throughout Wickramasinghe’s writings on art and literary criticism, as well as in the prefaces to several novels and collections of short stories, he explains the conceptual principles he has made use of. Theorising the authenticity and artistic merit of Buddhist Pali and Sinhala literature, Wickramasinghe views them as social manifestations of silent protests by the ‘common people’ (podu janathawa) against the social, cultural, and intellectual domination of the elite classes. Wickramasinghe’s extensive discussions on pre-modern Sinhala literary texts such as Sinhala Jathaka Potha (‘Sinhala Jathaka Tales’), Buthsarana (‘Taking Refuge in the Buddha’), Saddharma Ratnavaliya (‘Gem-Studded Garland of the Buddha’s Teachings’), Umandawa (‘Tales of the Tunnel’), Kavyashekaraya (‘Pinnacle of Poetry’), and Guttila Kavyaya (‘Life of Guttila in Verse’) advance the following thesis: the artistic excellence of all these works is rooted in the ability of their authors to defy and resist the brahminic and Sanskritic alamkaravada and rasavada traditions of aesthetics; and in turn invent a socially grounded, indigenous, and therefore truly authentic frame of literary imagination.

Wickramasinghe’s discovery of the hermeneutics of defiance among the peasant artists, writers, and dissident Buddhist monks engaged in writing prose and poetry paralleled with his recognition of the historically situated ‘social question’ as the fundamental factor that had contributed to shaping the discourses, evaluations, and judgments in artistic-literary creation and criticism evolved in the pre-European colonial Sinhalese society. In works such as Sinhala Lakuna, Sinhala Sahithyaye Nageema, Vichara Lipi, Sinhala Vichara Maga, and Guttila Geethaya (‘Song of Guttila’, first published in 1943), Wickramasinghe has employed a non-idealistic, semi-materialist and socially-rooted historiographical approach to writing the literary, artistic, and cultural history of Sinhala society. This is a major part of Wickramasinghe’s originality as a cultural theorist that still awaits acknowledgement. The period within which Wickramasinghe produced all the above works of literary criticism was also the time the Left and the working-class movements had a major influence on Sri Lanka’s political and intellectual domains.

Worldview-Driven Literary Production

My second observation is as follows. Another way of recognising Wickramasinghe’s identity as a novelist and short story writer is to acknowledge him as a writer who treated his literary work as a platform to present his own worldview. That, in turn, made him what may be called a ‘thesis-driven fiction writer’.[2] When Wickramasinghe began writing novels and short stories, Piyadasa Sirisena, a prominent Sinhala novelist at the time, was the foremost worldview-driven, or ideological, fiction writer in Sri Lanka. Sirisena used his fiction and poetry to propagate the freshly emerged ideology of Sinhala Buddhist and anti-colonial nationalism in its political as well as cultural versions.

Wickramasinghe, however, diverged from Sirisena’s worldview from the outset and critiqued it with his own alternative ideological perspective with secular, liberal, and humanist leanings. Both his first work, the novel Leela, published in 1914, and his final work, Bavatharanaya, published 49 years later, epitomise his occasional fascination with the genre of strong-thesis fiction. Leela was a novel that directly expressed the author’s worldview which was shaped by liberal secularism and European scientific epistemology. This was in opposition to Piyadasa Sirisena’s Sinhala Buddhist ethno-nationalist ideology as well as the epistemology of the traditional belief systems. What this means is that the very raison d’etre of the novel rests on its ideological logic, not on the aesthetic value as a work of modern fiction. On the other hand, Wickramasinghe’s novels such as Gamperaliya (‘A Village Transformed’, 1944), Yuganthaya (‘End of an Era’, 1949), Viragaya (‘Devoid of Passion’, 1956), Kaliyugaya (‘Era of Darkness’, 1957), and Karuvala Gedera (‘Dark House’, 1963) can be identified as ‘soft-thesis fiction’. In strong-thesis fiction, Wickramasinghe openly presents his worldview in the preface, through the narrative, character portrayal, chain of episodes, background descriptions, and dialogues. Thus, in the strong-thesis novel, the worldview of the author, which is explicitly articulated, becomes the novel’s basic organising principle, its leitmotif. Bavatharanaya stands as a key example of this approach, while Leela exhibited similar characteristics much earlier.

In Leela, the author begins the preface as follows:

“Nowadays, there is no book genre that spreads as rapidly among our country’s people as fictional stories. That is why I also intend to propagate the ideas included in it through fiction. It is difficult for us to determine whether the reading of fiction brings any good or harm to the reader. Our aim is not merely writing fiction but propagating the ideas it contains” (Wickramasinghe 2018: 7).[3]

The main ideological and therefore propagandist view presented directly in the preface of the novel and indirectly within is that, “the Sinhalese people should step forward to break away from the iron chain of traditional customs that shackles them”, thus attaining the “freedom necessary for their development”. The author also criticises the intellectuals of the day who advocate the blind acceptance of tradition and superstition:

Unfortunately, certain educated individuals in our country seek to enslave the Sinhalese people by depriving them of their freedom by shackling them to the traditional customs. If a nation is inferior in terms of [scientific] knowledge and civility, to that extent they are enslaved by the traditional habits and customs.” [4]

In Wickramasinghe’s novel Leela, the plot progresses through a chain of events, characterisation, and narrative logic that are designed to build a melodramatically enacted conflict between two ideological currents that prevailed amongst Sri Lankan intellectuals of the early twentieth century. The novel’s two main male characters, Albert and Gilbert, serve as direct representations of the clash between the liberal, rationalist, and scientific knowledge system that arrived from Europe and the traditional, culture-based, and belief-centric knowledge system championed by the nationalist intelligentsia. Constructed within a simple and arguably unsophisticated narrative framework, Albert who worships the greatness of modern scientific knowledge, serves as an agent of the author’s own worldview. This is not unusual for strong-thesis fiction. In fact, a common element of the strong-thesis genre is the author’s tendency to totally identify with a character, where the character’s voice becomes the medium for the author’s own propagandistic intent. The novel’s plot progresses, to expose Gilbert, Albert’s foil and of course the embodiment of the conventional social norms and values, as morally duplicitous. Gilbert is a man with moral double standards towards Leela, the young woman he is determined to marry for personal gain. He is portrayed as a cunning and cruel man with an utterly selfish personal agenda. At the end of the novel, Gilbert, who also represents the dark side of the superstition-ridden village culture, meets a tragic end when his house catches fire. Albert, in a display of personal heroism and a sense of valour, rescues Gilbert from the fire. Yet, Gilbert could not survive the burn injuries. Gilbert dies in Albert’s arms, making a confession of his misdeeds. The scene of Gilbert’s sad death serves as a melodramatic moment of poetic justice. The climax is a highly sensationalised representation of the triumph of modern scientific temper, which a man of moral integrity embodied, over a man belonging to the old world of moral duplicity. The plot of Leela also symbolises the epistemological clash between colonial modernity and anti-colonial cultural nationalism that unfolded in Sri Lanka during the early decades of the twentieth century.

By contemporary standards of literary criticism, Leela as a novel can be seen as both naive and propagandist, and an unabashedly ‘ideological’, novel. It serves as both a direct response to and a challenge against another strand of ideological novels that carried Sinhala nationalist messages. The latter being a genre popularised by Piyadasa Sirisena, a prominent Sinhala journalist, poet, and fiction writer inspired by the nationalist thought and activities of Anagarika Dharmapala. Sirisena was the leading populariser – through fiction, poetry, journalism, and preaching – of the ideology of Sinhala Buddhist cultural nationalism initiated by Dharmapala during the 1890s. Leela’s Gilbert is obviously an over-dramatised and one-dimensional representative of Piyadasa Sirisena’s cultural nationalist cadres. Although an artistically weak but ideologically strong novel, Wickramasinghe’s Leela can be placed within the early stages of the evolution of Sinhala fiction as a novel with its own ideological and polemical qualities.[5] Similar to Piyadasa Sirisena’s novels, Martin Wickramasinghe’s Leela represents the period of strong-thesis Sinhala fiction.

Subsequently, Sinhala fiction made a transition into a phase of soft-thesis and non-ideological novels and short stories. Interestingly, Martin Wickramasinghe happened to be the pioneer and the most prolific representative of the soft-thesis genre of Sinhala fiction. Soft-thesis novels refrain from engaging in ideological indoctrination or battles among competing worldviews. They usually have an unstated worldview which is often part of the author’s philosophy woven into the text in a subtle and restrained manner. Its discovery may demand reflexive and interpretative reading from the reader.

The fact that Wickramasinghe’s final novel, much like his debut work, is a strong-thesis fiction warrants our attention. Bavatharanaya’s main character, Siduhath, is constructed to embody a rationalised, de-mystified, and socially egalitarian Buddhism with which the author identified.[6] It proposes, and employs, a rationalist mode of re-framing the biography of the Buddha while also offering a socially grounded approach to re-imagine and re-interpret the life and the philosophical thought of the Buddha. Moreover, it challenges, through the medium of the main character, Siduhath, the conventional traditions of biographising the Buddha’s life as well as presenting his thought and work. The author also directs Siduhath and several other characters to engage in philosophical discussions and debates on existential and ontological questions, the likes of which are usually not found in contemporary Sinhala literature. Nevertheless, these debates serve as a platform to facilitate the philosophical positions of the Buddha as well as the author to prevail. Bavatharanaya can also be distinguished as a ‘philosophical novel’ because of its depiction, so cleverly woven into the main narrative of the novel, of the metaphysical controversies among different philosophical and religious schools on the soteriological question of human emancipation during the Buddha’s time in North India. Whose side the author is on is no secret to the reader. That seals the strong-thesis character of Bavatharanaya, suggesting even that the philosophical partiality of the author has negative consequences for the novel’s artistic accomplishments. Ediriweera Sarachchandra, during the height of the Bavatharanaya controversy in 1973, wondered whether the narrative had become “far too cerebralised and bereft of the emotional quality proper to a work of fiction” (Sarachchandra 1973).

In the preface of Bavatharanaya, the author directly presents his ideological position regarding the life of Siduhath and later the Buddha’s teachings. By challenging and rejecting the conventional metaphysical traditions of biographising the Buddha, Wickramasinghe proposes and employs a radically new approach for narrating the life of Siduhath and the Buddha. He calls it the ‘rule of realism’, or yathartha rithiya. At the beginning of the preface, the author introduces this unconventional narrative strategy as follows:

“Every biography of the Buddha has been written in line with the principles and rules of alamkaravada which the Buddha himself had rejected. It was the brahmins who compiled the versified narratives of the lives of Vedic gods called Purana by giving an exaggerated prominence to the mystified Alamkaravada rules which the Buddha himself had denounced. This exaggerated mysticism and the mystifying narrative rule influenced not only the Pali commentaries but also the biographies of the Buddha. In writing my novel on Siduhath’s biography, I departed from this mystifying tradition and its rules, opting instead to embrace realism and its rules” (Wickramasinghe 1973: 7-8).[7]

In writing Bavatharanaya the author not only rejects the traditional narrative rules in depicting the Buddha’s life. He also questions the ways in which the Buddha’s perspective of emancipation are misrepresented in the brahminised traditions of re-constructing the Buddha’s biography. Proposed in its place is a radically new and socially grounded approach to reimagine the life and accomplishments of the Buddha. Thus, the author presents an extraordinarily innovative interpretation of the Buddha’s efforts and teachings; one that is totally detached from other-worldly, supernatural, or transcendental histories and events. This new approach frames the Buddha’s life, thoughts, and teachings entirely in this-worldly and therefore secularised terms. The author explains his effort as follows:

“The paths of emancipation developed by the sages who came before the Buddha in India were tailored for the brahmin, kshastriya, the wealthy, and the trading castes. The Buddha’s teachings and path catered to the people from chandala, bonded labourer, farmer and shepherd castes as well as khastriya, brahmin, wealthy and merchant castes. However, because of the Buddha’s teachings, there arose an awakening and a revolution among the common people. It shows that Siddhartha Gautama renounced his worldly life not just to attain personal salvation from the cycle of birth, suffering, and death. Through this novel I attempt to reveal that Siddhartha Gautama left the worldly life to seek a just path for the people who were enduring immense suffering due to caste divisions and social injustices” (Wickramasinghe 1973: 8). [8]

Leela and Bavatharanaya together show that strong-thesis works of literature also have the capacity to evoke partisan responses, harsh objections, and even organised hostilities due to the power of the ideology they happen to undermine or propagate. In the preface to the novel Leela, the author recounts how two individuals who read the manuscript before its publication reacted angrily. One of the author’s “very patriotic” friends, upon reading the manuscript, denounced him by commenting that there was “no one more stupid than you in Sri Lanka” to write a novel like this. Another friend’s advice was: “If you publish this book, you will be severely condemned. Therefore, refrain from printing it.” Sarathchandra notes that when Leela was published, “the whole of the orthodoxy were up in arms” against Wickramasinghe. To make matters a little more complicated, when a Christian newspaper, Rivi Kiraana, had a favourable review of the book, the author was “branded a Christian, a dubious compliment at the time” (Sarathchandra 1950: 133-34).[9]

Five decades later, Bavatharanaya, Wickramasinghe’s last creative work, received an intensely hostile response. The author was accused of insulting Prince Siddhartha and the Buddha. The hostility quickly led to a Buddhist protest movement that lasted for many months. The protestors demanded from the government that the novel be banned under the emergency law and the author be prosecuted. Amidst this opposition, a counter-agitation movement comprising of writers, artists, intellectuals, and Buddhist monks emerged in support of the novel and its author. Their main defence of Bavatharanaya and its author was that a realistic and rational rendering of the life of the Buddha, free from mystifying exaggerations and distortions, had been long overdue and that Wickramasinghe had restored the human side of the Buddha’s life by employing a ‘realist’ approach to biographise the early phase of the Buddha’s life. The protest movement ended when the Sri Lankan government rejected demands to ban the novel. True to its strong-thesis character, the reactions which Bavatharanaya received from critics and defenders alike were entirely inspired by their competing ideological commitments.

A strong-thesis novel can also acquire a unique and unusual life story for itself. Two main features and trends in the extraordinary life story of Bavatharanaya the novel can be identified. First, the community of readers as well as the social responses to the novel became sharply polarised into two adversarial camps of enemies and friends. Second, political space for hostile state intervention through invitation became a tangible threat to the novel as well as its author. Although it did not happen with Bavatharanaya, a novel or a work of art may face this risk when its central tenets directly challenge the established beliefs built into the religious or cultural orthodoxies. Several examples from South Asia illustrate this possibility of invited state action. For instance, Aubrey Menen’s book Rama Retold, published in 1954, was banned on charges of insulting Hinduism. The novel was a satirical, and of course irreverent, re-telling of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Menen, an Indian writer of Kerala origin, was hounded by right-wing Hindu political forces. Discouraged by the not-so helpful actions of a secular government, Menen relocated himself to Britain for some time. Salman Rushdie and his novel, The Satanic Verses, published as recently as 1988 aroused so much anger among Islamic communities and some States that he was forced into hiding and recently narrowly survived an attempt on his life that has left him blind in one eye. The renowned Indian artist M. F. Hussain was forced into self-exile by right-wing Hindu groups who saw him as having insulted Hindu goddesses in his paintings. In all these instances, either questioning, ignoring, or revising religious tenets and cultural mythology constituted blasphemy, an offence punishable by varying degrees of hostility, denunciation, death threats, and assassination.

However, the author of Bavatharanaya did not meet a fate similar to that of Menen, Rushdie or Hussain, perhaps for three main reasons. Firstly, there was significant public agitation in the country in support of the novel, its author, and its ideological standpoint. A large number of intellectuals, writers, artists, and Buddhist monks came forward to publicly express their admiration of the realist and humanist approach employed in the portrayal of the Prince Siddhartha-Buddha character of the novel. Secondly, the government in power did not dare to persecute Martin Wickramasinghe, the leading and senior-most Sri Lankan writer and cultural critic at the time who also enjoyed considerable public support and popular admiration. Thirdly, and perhaps more importantly, Sri Lanka’s general political climate in the early and mid-1970s, even amidst political instability and under a state of emergency, had not closed the space for cultural and artistic dissent. Three years after Bavatharanaya’s publication, in 1976, the author died at the age of 86. No Sri Lankan writer since has dared to produce any work of fiction that would be viewed as even marginally transgressive of religious-cultural orthodoxies. State harassment to dissident writers occurs in contemporary Sri Lanka through police and judicial actions, justified ironically through the application of an ostensibly minority and human rights protection law enacted to give effect to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

II

After this background discussion, we can now shift our focus to sharing reflections on the collection of short stories titled Gahaniyak. I want to make two initial observations. Firstly, this short story collection represents a turning point in the progression of Wickramasinghe’s journey as a creative writer. To re-state my point slightly differently, Gahaniyak can be viewed as signifying a transition in Martin Wickramasinghe’s literary imagination from the strong-thesis approach to fiction, as seen in his novel Leela, to a soft-thesis approach. Secondly, when Wickramasinghe, a novice to writing fiction, produced his first collection of short stories in 1924, he had re-constructed his own worldview with some clarity and consistency along with a set of interpretative principles to lay bare the social world.

Across all the short stories in Gahaniyak, there is a distinct authorial worldview and a principle employed by Wickramasinghe to interpret the social world. It is a worldview, or a personal philosophy, of empathic compassion towards the poor, the marginalised, the insulted, and the condemned individuals in society in a Dostoyevskyian spirit. Wickramasinghe’s subsequent short story collections Handa Saakki Keema (‘The Moon Bears Witness’, 1945) and Wahallu (‘Bonded Labour’, 1951), written later, echoed this worldview of empathic compassion. Wickramasinghe added a somewhat long essay called ‘The Short Story’ to Wahallu as an Appendix to provide some inspiration as well as guidance to young writers. There he re-asserted the normative principle that he had been emphasising as the defining feature of great literary work, that is, the empathic depiction of the life of ordinary men and women, or ‘podu minisun’ (‘small people’). In Wickramasinghe’s view, the greatest novels written by the Western novelists depicted “not the life of kings or ministers, but the life of the common people”. What inspires the creative imagination and the vision of great novelists are “not what happens in the conventional life of the kings and their ministers, but the everyday life of the common people who struggle day in and day out with a thousand and one hazards and misfortunes” (Wickramasinghe 1951: 137).

Through many of his short stories, Wickramasinghe as the author also invites readers to cultivate an ethic of empathic compassion towards those who have no escape from oppressive social or personal circumstances. In that sense, Wickramasinghe’s short stories can also be seen as a series of dialogues between the author and the reader about the fate of the ‘common people’ (podu janathawa), a social category which the author constructed in his creative work and the writings of cultural criticism. The normative ethical principle in Wickramasinghe’s final creative work, the novel Bavatharanaya, is also the empathic compassion towards social groups as well as individual men and women whose destiny is subjected to marginalisation, oppression, and humiliation in society. Since he wrote Gahaniyak, this ethic seems to have constituted the core principle of, to use a contemporary expression, ‘the inclusion of the excluded’ into the normative agenda of both literary and critical imagination.

As depicted in many of Wickramasinghe’s short stories and novels, empathic compassion is a feeling that resides in a moral space beyond the feelings of mere sympathy. If we look at it from a phenomenological perspective, empathic compassion prepares the grounds in our consciousness for an ‘empathic understanding’ of the feelings of fellow human beings who find themselves trapped in conditions of socially produced misfortunes and anguish. The preface to Gahaniyak enables the reader to transform their empathic ‘compassion’ into empathic ‘understanding’ at a higher level of critical consciousness. In other words, empathic understanding necessitates a passage from the domain of emotions to the domain of cognition and critical reflection. It also assists us to build a capacity to comprehend and react to the predicament of others from their own experiences, perspectives, and feelings. Impulses for artistic creativity begin in the domain of empathic emotions. In Wickramasinghe’s scheme of artistic creation, as suggested in the preface to Gahaniyak, it is the immediacy of the “heart-felt emotions” rather than the “intellect” that can inspire creative imagination (Wickramasinghe 2019: 7).

In the same preface, Wickramasinghe provides brief explanations informed by his own outlook and vision that guided his creative impulses to construct the central characters of each short story in the collection. Through those explanations the reader gets an insight into the conscious efforts made by the author to depict what he calls the ‘full humanity’ of the powerless men and women he personally knew in his own social surroundings. As Wickramasinghe claims, in the first short story Begal (‘Yarn Spinner’), through the character of Ando Aiya, he tries to reproduce “a tiny drop of a character type” which had almost totally disappeared in rural society. Ando Aiya makes a living by entertaining his fellow villagers at the wayside teashops by telling them concocted tales of his unbelievable quixotic adventures. When the author refers to Ando Aiya as “a human” (manushyayaku), it is not merely in the immediate sense that he is a man or a human being, but rather in the sense that he represents the essence of a personality type through the “weaknesses and innocence that are ingrained in his character”. According to Wickramasinghe, it is the author’s intrinsic capacity to possess such a deep sense of empathy (dayanukampawa), as revealed through the ways in which the characters are portrayed, that defines the greatness of a work of literature (Wickramasinghe 2019: 8).

This emphasis on empathic understanding reflects Martin Wickramasinghe’s phenomenological insight into human nature that in turn enables the reader too to see, through the innocent eyes of the narrator who is a young schoolboy, the ‘human condition’ (manushyathmabhavaya)[10] of the individuals in rural society who are rendered powerless and even useless by the forces of rapid social change facilitated by colonial capitalism.

“Ando Aiya, or Begal, is a man who lived everywhere until recently, but is gradually becoming extinct due to the spread of Western civilization and the easy availability of books. The story of Begal offers a glimpse into that man’s character … His weaknesses and innocent qualities alike are portrayed. The small village boy depicted in the story also vividly comes to life through Ando Aiya (Wickramasinghe, 2019: 9).[11]

The short story Kuvenihaamy depicts the tragic life of a young woman impoverished, powerless, and subjected to severe exploitation and oppression by societal norms and power structures. It serves as a phenomenological study of the suffering of a woman abandoned to a life of misery and misfortune by men of her own social class as well as by the elites. The narrative presents Kuvenihaamy’s wretched existence and bitter personal ordeals in her encounters with these two sets of men: one with urban working-class backgrounds; and the second, respectable men of the elite.

Kuvenihaamy is a young rural woman who comes to the city as a domestic worker in the household of a rich Burgher family. There she gets romantically attracted to a young man who visits her employer’s family frequently. With her lover, she develops an intimate relationship with no moral inhibitions.[12] Kuvenihaamy soon gets pregnant and loses her employment. Her rich young lover abandons her. Helpless, yet with resolve, she manages to survive with her baby son. She could not go back to her village since she had a child out of wedlock. Kuvenihaamy moves to a working-class slum area of Dematagoda in Colombo and begins to live with an elderly woman who earns her living doing odd jobs for fellow slum dwellers. After her son is born, Kuvenihaamy runs out of her meagre savings and finds herself with no means to survive. In the meantime, a young tramcar driver, who is also a migrant worker to the city from a rural village, gets attracted to the beauty and charm of Kuvenihaamy. Seeking love and protection, she gets married to him. They live together for five years. The man loses his job and goes back to his village, abandoning Kuvenihaamy. Feeling helpless, Kuvenihaamy decides to live with a Malayali migrant railway worker of South Indian origin, Kunji Raman, who was living in a room in the same row of shanties. Although Kunji Raman loved Kuvenihaamy because of her beauty, he hated her son who did not have a father. Kunji Raman, often drunk, subjects the little boy who is undernourished, sick, and skinny, to regular scolding, beating, and cruelty. To escape this state of utter misery, Kuvenihaamy runs away from Kunji Raman and begins to live with a carter. Driven by intense jealousy and rage, Kunji Raman searches for Kuvenihaamy. One day he finds her near the Colombo Eye Hospital with her sick son. Severely drunk, he forcibly brings them home and starts mercilessly beating and torturing both mother and son. To save the son from further torture, she attacks Raman with a kitchen knife. He dies of a severe head injury.

It is in the second part of the story that Wickramasinghe builds up his own role as a social critic with a reformist agenda, giving the story’s final chain of events a melodramatic twist. Kuvenihaamy is tried for murder. The jury foreman happens to be her first lover and the father of her son. The court scene as the final episode of the story is constructed as the culmination of a brutal encounter between a helpless and powerless woman and a gang of selfish, cruel, morally impoverished, and insensitive men with so much power over her life – head of the jury, the prosecuting lawyer, and the judge. They convict her for murder. While awarding Kuvenihaamy the death penalty, the three men solemnly agree that it was their moral duty to “protect society from such a dangerous woman gone mad with an insatiable sexual urge”.[13]

Interestingly, Kuvenihaamy has a structural hybridity in the way in which the author handles the representation of the worldview he has built into the story. It begins as a short story driven by a soft-thesis, and ends as one driven by a strong-thesis. The moralising tenor of the author’s comments woven into the text and the narrative structure suggests that Wickramasinghe had not yet fully settled accounts with the strong-thesis genre of Piyadasa Sirisena tradition. That is perhaps why the shadow of Leela’s strong-thesis spirit has entered the latter part of Kuvenihaamy.

Nevertheless, the short story enables the reader to participate in empathic contemplation on the predicament of Kuvenihaamy and the tragic vicissitudes of the human spirit. The overwhelmingly oppressive presence of patriarchy, producing direct and indirect violence against her, is a subtle subtext present throughout the story. This story, like others of its kind, engenders a double empathy: one stemming from the author’s worldview and another from the reader’s contemplation on Kuvenihaamy’s world of misfortune, prompted, specifically in this story, by the author’s soliloquist commentary. The creation of such a frame of double empathy can be seen as a distinct characteristic of Martin Wickramasinghe as a creative writer. Wickramasinghe’s later short story Wahallu and the novel Viragaya serve as compelling examples of this double empathic approach with greater narrative sophistication with no room for the author’s commentarial interventions.

Gahaniyak, first published in 1924, stands as Martin Wickramasinghe’s first collection of short stories. Before this, he published four novels: Leela (1914), Soma (1920), Irangani (1923), and Sita (1923). Notably, there exists a narrative complexity within each short story included in Gahaniyak surpassing the narrative simplicity and minimalism found in those four novels. In his autobiography titled Upanda Sita (‘My Life Since Childhood’, first published in 1961), Wickramasinghe himself refers to Irangani and Soma as childish romances (Wickramasinghe 2017: 252).

When one carefully reads the preface and the stories in Gahaniyak, it becomes evident that a fundamental transformation of Wickramasinghe’s artistic imagination had occurred during the 1920s. It is his acknowledgement that literary creation requires the portrayal of the complexity of human nature from a perspective of empathic understanding. This transformation is also evident in the short stories of his later works such as Handa Saakki Keema and Wahallu. This evolution of Wickramasinghe’s mature worldview is particularly evident in the preface of Gahaniyak. This sensitivity to, and understanding of, the complexity of human life and characters seems to have enabled him to transcend the simplistic framing of men and women of dispossessed social backgrounds. The preface to Gahaniyak concludes with the following passage:

“Some of the stories depicted here portray the difficult situations faced by both women and men as they navigate through the challenging life circumstances, grappling with the mental and emotional burdens, societal norms, and social customs that determined their actions” (Gahaniyak 2019: 12).[14]

Readers will not find the word ‘empathy’ in Martin Wickramasinghe’s vocabulary. Nor is there evidence to suggest that he has engaged with the works of philosophers associated with phenomenology, a philosophical movement in modern Europe active during the early decades of the 20th century. However, this should not hinder us from recognising the phenomenological essence and characteristics of Wickramasinghe’s own artistic-literary vision. Wickramasinghe’s phenomenological sensitivity to the human condition seems to have been inspired by two distinct sources, Buddhist Jataka stories and the European realist novel, particularly English, French, and Russian. A passage that can be interpreted phenomenologically although it is not written in the philosophical language of phenomenology, can be found in the preface to the 1936 collection of short stories titled Pawukarayata Gal Gaseema (‘Stoning the Sinner’):

“The rational capacity of those who contemplate only on the wickedness inherent in the human nature can be easily overwhelmed by hatred. However, what is provoked in those who can see both the wickedness and goodness alike of the human nature is a feeling of sympathetic neutrality.”[15]

In this passage, Wickramasinghe suggests that both the writer and the reader should cultivate a sense of “sympathetic neutrality”, that is, a sense of empathy, without passing any moral judgements. The empathy’s object is not merely the characters of the story; rather, the humanity to which they belong.

III

Martin Wickramasinghe’s short stories, novels, and works of literary criticism are distinguished by some other unique elements too. In the short story collection Gahaniyak, two such elements stand out: the concept of the ‘common people’ and the belief that exploring the ‘social question’ through literary works ensures their authenticity. Both these elements serve as guiding principles in the search for the social meanings of Wickramasinghe’s short stories as well as the foundational assumptions of his creative and critical thought.

The concept of the ‘common people’ serves as a trope that reflects Wickramasinghe’s worldview as a creative writer and a literary critic. It also reveals his own ideological identity. The concept of ‘common people’ figures frequently in his final novel Bavatharanaya. The preface to the first print of the novel in 1973 has the following statement: “An awakening and a revolution also took place among the common people because of the Buddha’s teachings”. Wickramasinghe elaborates which social groups are included in this category of ‘common people’. Among them are chandalas (සැඬොලුන්), bonded labourers (දාසයන්), goldsmiths (රන්කරුවන්), barbers (කරණවෑයමින්) and even criminals. They are among the ‘common people’ who were ‘awakened’ by the Buddha’s teachings.

In the preface to the third print of Bavatharanaya in 1975, Wickramasinghe broadens the semantic scope of ‘common people’ to explain and justify, in the face of hostile criticisms, the non-elitist and de-Sanskritised narrative strategy of ‘realism’ which he employed in Bavatharanaya. His choice of a ‘realist’ narrative strategy was an essential component of a larger project of de-Sanskritising, de-brahminising, and secularising the art of writing the Buddha’s biography. In the novel, he boldly reconstructed the biography of Siduhath as a revolutionary social reformer.

Accordingly, he framed the Buddha’s teachings as also a this-worldly liberationist doctrine meant for the ordinary people who were crushed by the oppressive caste and class structures that existed in North Indian Hindu society. While doing so, Wickramasinghe emphasised the point that the Buddha communicated his teachings in a common people’s language accessible to all, including kings, brahmins, wealthy traders, peasants, workers, and bonded labourers. Thus, the ‘common people’ or podu janathawa, had a double significance in Wickramasinghe’s story of Buddha retold. They were not only the key social constituencies that embraced the Buddha’s teachings as a path to social and spiritual emancipation, freed from the oppressive domination of social and spiritual elites. The Buddha also used a local language of the podu janathawa – not Sanskrit which was the language of the brahminic elites – as the medium to propagate his liberationist philosophy, specifically for the ordinary people in their own language and idiom.

The point we need to acknowledge here is that Martin Wickramasinghe had begun to develop an approach by the early 1920s that would recognise the centrality of the social in literary work as well as cultural critique. It is an approach that recognised the socially situatedness of literary texts, their authors, and their aesthetic claims. In fact, as his numerous writings on Sinhalese literature and culture show, Wickramasinghe was the first Sri Lankan scholar to recognise the social connectedness of both language and literature. Moreover, this was well before Marxist social theory began to have some influence on social and cultural analysis in Sri Lanka. The other observation we can make here is that far earlier than the notion of the concept of ‘common people’ was used in the Sri Lankan academic or political discourse, Wickramasinghe seems to have begun to produce a body of creative and critical work employing, implicitly and explicitly, the category of podu janathawa, that is, ‘common’ or ‘ordinary’ people. This was a decade prior to the emergence of the Left movement in Sri Lanka, that popularised the notion and discourse of ‘common people’. Wickramasinghe’s collection of short stories, Gahaniyak published in 1924, can be seen as an early example of an approach centred on the common or downtrodden people being depicted in literary production.

The seven short stories in Gahaniyak and those in Wahallu draw the reader’s attention to the lives of women, men, children, dogs, and cattle in a village in the southern province of Sri Lanka during the last century. These were lives that were trapped in an incessant struggle for survival with the consequences and shocking manifestations of rural poverty. Wickramasinghe’s portrayal of society and life through these characters highlights the struggles faced by subaltern social strata, who are victims of the structural cruelties and everyday tyrannies prevalent in Sri Lankan colonial rural society. Wickramasinghe deploys the term ‘podu janathawa’ (‘common people’) to describe these men and women who are marginalised within the structures of economically stagnant rural semi-peasant society. Through these short stories sans many heroes or villains, Wickramasinghe appears to invite the readers to understand with empathy the life world of men, women, children, and even animals who are grappling with the deprivations in everyday life amidst oppressive social structures, customs, value systems and normalised cruelty. For Wickramasinghe, an awareness of these conditions of human misery evokes a sense of what he calls පහන් සංවේගයක්, or an emotion of empathic equanimity. We should not be surprised if Wickramasinghe faced criticism from left-wing or radical literary critics for not encouraging readers to probe beyond this perspective of empathic equanimity. Wickramasinghe’s moderation in worldview advocacy in Gahaniyak is perhaps because when he penned these stories for the volume, he had moved away from the strong-thesis driven approach employed in the novel Leela.

Thus, ‘empathic understanding’ emerges as the fundamental intellectual experience available to the reader from Wickramasinghe’s novels and short stories published after Gahaniyak. It is an understanding shaped by the awareness, shared by both the author and the reader, of the unalterable objective logic of the social and cultural conditions that produce and reproduce human misery encountered by the characters of the short stories. Wickramasinghe, for example, states the following in the preface to the book Gahaniyak about the story titled Irunu Kabaaya (‘The Torn Jacket’). In this story, “although some of the weaknesses of the villagers, which are laughed at by the common people, are woven into the narrative, those weaknesses are not to be mocked; rather, they evoke compassion and respect from the educated” (Wickramasinghe, 2019: 11). A similar sentiment is echoed in Wickramasinghe’s explanation of the short story Mother. The story depicts “the suffering as well as the tragic side of life. It illustrates how a rural woman, driven by compassion for others, was forced to suffer more because of her own compassionate nature … Like a duck takes to water, she, with a heart brimming with compassion, gave priority to the pain and happiness of others over her own well-being” (Wickramasinghe, 2019: 11).

The term dayanukampawa (‘daya’ + ‘anukampawa’ or ‘compassion’ + ‘sympathy’) which Wickramasinghe uses frequently, merits the reader’s attention as it is a key signifier of the writer’s empathic intentionality.[16] It also serves as a guiding principle for the empathic understanding he seeks to evoke in the reader. Therefore, none of the human characters depicted by Wickramasinghe in his short stories are one-dimensional. It is also for this reason of subdued, as opposed to passionate, advocacy of moral choices that the short story collection Gahaniyak qualifies to be recognised as a soft-thesis driven work of fiction, with path-breaking artistic merit.

Jayadeva Uyangoda is Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the University of Colombo.

References

Coomaraswamy, Ananda. (1918). The Dance of Shiva: Fourteen Indian Essays. New York: The Sunwise Turn, Inc.

Sarathchandra, E. R. (1950). The Sinhalese Novel. Colombo: M. D. Gunasena & Co. Ltd.

Sarachchandra, Ediriweera. (1973). “The Buddha through a Novelist’s Eye”, Ceylon Daily News, December 06 1973.

Wickramasinghe, Martin. (1963). Pawukarayata Gal Gaseema (‘Stoning the Sinner’) [1936]. Maharagama: Saman Press.

——-. (1979). Bavatharanaya (‘Crossing the Ocean of Samsara’ [1973]. Rajagiriya: Sarasa Publishers.

——-. (2015). Sinhala Vichara Maga (‘The Path of Sinhala Literary Criticism’) [1964]. Rajagiriya: Sarasa Publishers.

——-. (2017). Wahallu (‘Bonded Labour’) [1951]. Rajagiriya: Sarasa Publishers.

——-. (2017). Upanda Sita (‘My Life Since Childhood’) [1961]. Rajagiriya: Sarasa Publishers.

——-. (2018). Leela [1914]. Rajagiriya: Sarasa Publishers.

——-. (2019). Gahaniyak (‘A Woman’) [1924]. Rajagiriya: Sarasa Publishers.

——-. (2019). Sinhala Lakuna (‘Identity-Marker of the Sinhalese’) [1947]. Rajagiriya: Sarasa Publishers.

Notes

[1] This is an extended English version of a talk delivered in Sinhala (https://www.kinihiraya.org/geheniyak-by-jayadeva-uyangoda) by the writer at the seminar on ‘One-Hundred Years of Sinhala Short Story and the Publication of Gahaniyak’, held at the Department of Sinhala, University of Colombo, on 5 March 2024. The author’s sincere thanks are due to Ammaarah Nilafdeen for her translation of the original remarks from Sinhala to English, Apsara Karunaratne for her assistance to Ammaarah, and Sanjay Dharmavasan for copy-edits on the expanded English version. Any mistakes and inadequacies that might remain in the text are mine.

[2] My formulation ‘thesis-driven fiction’ is an attempt to identify the genre of novels and short stories that have an explicit ideological orientation, often to advocate a specific political or philosophical perspective. In my view, calling such fiction as ‘ideological’ is too simplistic and dismissive to capture the fusion of ideology and aesthetics in such works of fiction. All such works have a central thesis to advance, which is presented either directly and forcefully, or indirectly and in a framework of artistic subtlety and sophistication. In this essay, I call the first type ‘strong-thesis fiction’ and the latter ‘soft-thesis fiction’. My notion of ‘thesis-driven fiction’ is partly inspired by the French concept roman à thèse (‘thesis novel’).

[3] “වර්තමාන කාලයෙහි ප්රබන්ධ කථා මෙන්ම අප රට ජනයා අතර වහා පැතිර යන පොත් වර්ගයක් වෙන නොමැති ය. මෙහි අන්තර් ගත කරුණු ද ප්රබන්ධ කථා මාර්ගයෙන් ප්රකට කර හැරීමට අදහස් කරන ලද්දේ මේ නිසයි. ප්රබන්ධ කථා කියවීමෙන් කියවන්නාට අර්ථයක් සිදුවේද, එසේ නැතිව අනර්ථයක් සිදුවේ ද යන්න නිශ්චය කිරීමට අපි නොවෙහෙසෙමු. අපේ පරමාර්ථය ප්රබන්ධ කථා නොව මෙහි අන්තර්ගත අදහස් ප්රකට කර හැරීමකි’’ (Wickramasinghe 2018: 7).

[4] “අහේතුවකට මෙන් අප රට සමහර උගත් අය සිරිත් විරිත් නමැති යදම්වලින් බැඳ අප රට සිංහලයන්ගේ නිදහස නැති කොට ඔවුන් දාස භාවයට පත් කිරීමට උත්සාහ කරත්. යම් කිසි ජාතියක් ශාස්ත්රඥානයෙන් හා ශිෂ්ටාචාර භාවයෙන් යම් තරමකට පහත් ද ඔවුහූ එපමණකම සිරිත් විරිත්වලට වාල්වී සිටින්නාහ” (Wickramasinghe 2018: 7).

[5] E. R. Sarathchandra described Leela as a novel with “no special merits”, but a “remarkable work” because the opinions Wickramasinghe advanced in it “sounded nothing short of heresy” (Sarathchandra 1950: 133). Sarathchandra also noted that Leela appeared to be “a veiled attack on Piyadasa Sirisena and his novel Jayatissa and Rosalind” (ibid: 135).

[6] It is significant that Wickramasinghe in the novel does not call the protagonist of the story ‘Siddhartha’ which is the Sanskritised version of the Pali name ‘Siddhaththa’. ‘Siduhath’ is a simplified Sinhalese version of both Siddhartha and ‘Siddhaththa’.

[7] “හැම බුද්ධ චරිතයක් ලියැවී ඇත්තේ බුදුන් බැහැර කළ අලංකාර වාදය හා රීතිය අනුවයි. බුදුන් බැහැර කළ ඒ අද්භූත අලංකාර රීතිය අතිශයෝක්තියට නඟන ලද්දේ වෛදික දෙවියන්ගේ චරිත වස්තු කොටගෙන “පුරාණ” නමැති පද්ය කතා රචනා කළ බමුණන් විසිනි. පාලි අටුවා පමණක් නොව බුද්ධ චරිත රචනා ද කෙරෙහි අතිශයෝක්තියට නඟන ලද බමුණු අද්භූතවාදය හා රීතිය බල පැවැත්විය…. මගේ මේ සිදුහත් බුදුසිරිත් නවකතාව මා රචනා කළේ බමුණු සකු අද්භූතවාදය සහ රීතිය ඉඳුරා බැහැර කොට යථාර්ථවාදය හා රීතිය ගුරු කොටගෙනය” (Wickramasinghe, 1973: 7-8 පිටු).

[8] “බුදුන්ට පෙර ඉන්දියාවේ පහළ වූ මුනිවරයන් නිපදවූ දහම් විමුක්ති මාර්ග වූයේ බමුණු, කැත්, සිටු කුල ජනයාට ය. ඔවුන්ගේ දහම හා මාර්ගය සැඬොලුන්, දාසයන්, ගොවියන්, ගොපල්ලන් ආදීන්ගේ පටන් කැත්, බමුණු, සිටු , වෙළඳ කුලවල ජනයාද උදෙසාය… බුදුන්ගේ දහම නිසා පොදු ජනකාය අතර පිබිදුමක් හා විප්ලවයක් ද ඇති විය. සිදුහත් ගිහි ගෙය හැර ගියේ උපත, ජරාව, මරණය නිසා හටගත් කලකිරීමෙන් තමාගේ ආත්මය ගලවා ගැනීමට නොවන බව එයින් හෙළි වෙයි. කුලභේදය හා සමාජ ජීවිතය ද නිසා අපමණ දුක් පීඩා විඳිමින් ජීවත්වන ජනකායට එකසේ උචිත මාර්ගයක් සොයනු පිණිස සිදුහත් ගිහිගය හැර ගිය බව ද මේ නවකතාවෙන් හෙළි කරන්නට මම වෑයම් කෙළෙමි “ (Wickramasinghe 1973: 8)

[9] E. R. or Ediriweera Sarathchandra spelled his last name as “Sarachchandra” since the 1970s.

[10] Manushyathmabhavaya (manushya + athmabhavaya) literally means the ‘soul and existence of being human’. It may also simply mean the ‘human existence’.

[11] “අන්දො අයියා නොහොත් බේගල්, හැම පළාතකම මෑතක් වන තෙක් විසූ නමුත් බටහිර සභ්යත්වය පැතිර යාමත් පතපොත සුලභ වීමත් නිසා අන්තර්ධාන වීගෙන යන මනුෂ්යයෙකි. බේගල් නමැති කතා වස්තුවෙන් දැක්වෙන්නේ ඒ මනුෂ්යයාගේ චරිතයෙන් බින්දු මාත්රයකි…. ඔහුගේ දුර්වලතා මෙන් අහිංසක ගති ගුණ ද එක සේ නිරූපිත එම කතා වස්තුවෙන් චිත්රණය කරන ලද ගම්බද කුඩා දරුවාගේ ප්රතිමූර්තිය ද අන්දො අයියා නොහොත් බේගල් නිසාම ජීව ප්රාණය ලබයි” (Wickramasinghe 2019:9).

[12] In many of Wickramasinghe’s short stories and novels, women characters of poor social backgrounds are depicted as sexually uninhibited women of independent mind and a capacity to make decisions for themselves. Kuvenihaamy is a rural woman not governed by the traditional moral code that prevents women to have the capacity to make decisions for themselves. In Gamperaliya (first published in 1944), Yuganthaya (first published in 1949), and Kaliyugaya (first published in 1957), the elite women characters in the village as well as the city are generally caste or class conscious and at the same time morally conservative, tied to patriarchal cultural codes. In contrast, the peasant women enjoy a greater degree of freedom in relation to their sexuality, association with men, and socialisation. In Kuvenihaamy’s case, her sense of personal independence could not help her against the extremely harsh social circumstances of poverty and patriarchy.

[13] Kuvenihaamy is the name given to the main character, Diyunuhaamy, by the author. This unusual name resonates the key female character Kuveni, in the origin story of Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese community. According to the Pali chronicles as well as the popular versions of history, Prince Vijaya of Bengal landed in a port in Northern Sri Lanka. Having defeated the indigenous tribal communities in war, he soon became the first formal ruler, or the king, of Sri Lanka. Kuveni, according to the legend, was among the first group of native Sri Lankan inhabitants Vijaya and his entourage met. Vijaya and Kuveni developed a romantic alliance and became the parents of two children: a boy and a girl. Kuveni helped Vijaya to defeat in war members of her own clan called the Yakshas, and establish a new kingdom. After becoming a king, Vijaya abandoned Kuveni and married a princess from a royal clan brought from his father’s kingdom in Bengal. Kuveni goes back to her tribe along with her children knowing very well that she would be put to death by her kinsmen for her act of treachery in helping Vijaya. In Kalunika Seweema (‘In search of the Magical Plant of Kalunika’, first published in 1951), Wickramasinghe provides an interpretation that is deigned to restore Kuveni’s sense of moral integrity and self-respect amidst adversity emanating from men: her lover King Vijaya; and the male elders of her Yaksha clan. This is how Wickramasinghe re-reads the Vijaya-Kuveni legend: Kuveni left Vijaya and went on her own way because “Kuveni’s sense of self-respect and dignity did not let he remain in Vijaya’s harem as a second-level queen. To say that she wept aloud begging Vijaya not to abandon her, or to say that she retreated to the forest with her two children weeping aloud, is nothing but later additions to the legend made by the civilised who knew nothing about the bravery as well as the capacity for revenge among the ancient indigenous tribal communities” (Wickramasinghe 2023: 42). It is noteworthy that Wickramasinghe does not describe at all Kuvenihaamy’s emotions once the judge pronounces the jury’s verdict. He avoids melodrama, allowing the reader to reflect on his (the author’s) own reaction to the sheer immorality of the unholy coalition of power and patriarchy. Thus, Wickramasinghe’s short story of Kuvenihaamy can also be read as a modern parable of Kuveni.

[14] “මෙහි ඇතැම් කථාවස්තුවක් ජීවිතයෙහි දුෂ්කර වූ අවස්ථාවන්ට මුහුණපෑමට සිදු වූ ස්ත්රීන්ගේත්, පුරුෂයින්ගේත් ක්රියාකලාපයන්, ඔවුන්ගේ ඒ ක්රියාවන්ට තුඩු දුන් චිත්ත චෛතසික ධර්ම, සමාජ චාරිත්ර යනාදිය ද නිරූපණය කරයි” (Wickramasinghe 2019: 12).

[15] “මනුෂ්යත්වයේ දුෂ්ටත්වයම මෙනෙහි කිරීමෙන් කලකිරුණහුගේ බුද්ධීන්ද්රීය ද්වේශ පටලයෙන් වැසෙයි. මනුෂ්යත්වයෙහි දුෂ්ටත්වය මෙන් විශිෂ්ටත්වය ද දකින්නාහුගේ සිත් තුළ බොහෝ විට හටගන්නේ ද්වේශය නොව අනුකම්පාවට තුඩු දෙන උපේක්ෂාවකි” (Wickramasinghe, 1963:7).

[16] The Sinhala word dayanukampawa combines two emotions, dayawa, which is compassion, and anukampawa, meaning sympathy.

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...