The Election That Was

B. Skanthakumar

Sri Lanka has a new president. That the incumbent would lose was not in doubt. Who might replace him though was in question. Would it be opposition leader Sajith Premadasa, or the leader of a fringe party Anura Kumara Dissanayake? For months, the Colombo-based Institute for Health Policy (IHP) opinion polling on voting intention had them neck-to-neck, somewhere in the mid-to-high 30 percent range each. The incumbent Ranil Wickremesinghe trailed far behind. Until early August there was no declared candidate for the largest party in parliament, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP).

Shortly before election day, the final IHP poll favoured Dissanayake with a massive 23 percentage point lead over Premadasa. Though the survey correctly picked the winner, it overestimated the margin of victory, and the level of support for the third- and fourth-placed candidates, while underestimating the second-placed Premadasa’s share of the vote.

As the opinion surveys consistently bore witness, there was no candidate near the threshold of 50% +1 votes for a first-round victory. Therefore, the preference vote of those eliminated in the second round, would have to be distributed among the two leading contenders. This was a new experience for the electorate and the Election Commission alike.

In the event of a nail-biting finish, many expected Premadasa to pip Dissanayake when the second preferences votes were tallied. Surely those whose first choice was Ranil Wickremesinghe, and other traditional party candidates, were more likely to mark ‘2’ for another of the same ilk? Dissanayake’s campaign pitch, after all, was that he is the ‘disruptor’ of politics-as-usual.

It was such a long campaign. (‘Elections, finally!’ was how the Feminist Collective for Economic Justice titled their list of demands to the presidential hopefuls.) It began in earnest with the contest for local government bodies due in early 2023 – that Ranil Wickremesinghe unlawfully dodged claiming the treasury was bare. An unofficial campaign carried on from that point. Months before election day, many citizens just wanted it over. They had long made up their minds. Until Saturday morning dawned though, some of us fretted, wondering what foul trick Wickremesinghe would pull next, to stall his imminent eviction from office.

The number of electors was 17,140,354 from a population of almost 22.2 million (2021). Of this number, 1.1 million were first-time voters; young people affected in myriad ways by living through the COVID19 pandemic of 2019-20, the economic crisis that manifested from 2021 onwards, and the people’s uprising or Janatha Aragalaya of 2022.

The voter turnout on September 21 was 13,619,916 or 79.46% of those on the electoral register. In 2019, voter turnout was 83.72%. To put it another way, in 2024 over 3.5 million citizens were either unable or chose not to participate; which is a larger number than those who voted for the third-placed candidate. The number of spoiled or rejected ballots was 300,300 or 2.2% of votes cast, which is nearly the number of votes received by the fourth-placed candidate. Confusion in marking preferences, and difficulty in navigating the length of the ballot paper, may account for this amount. Only a tiny number even marked a preference beyond their first choice. It was an unfamiliar call upon them.

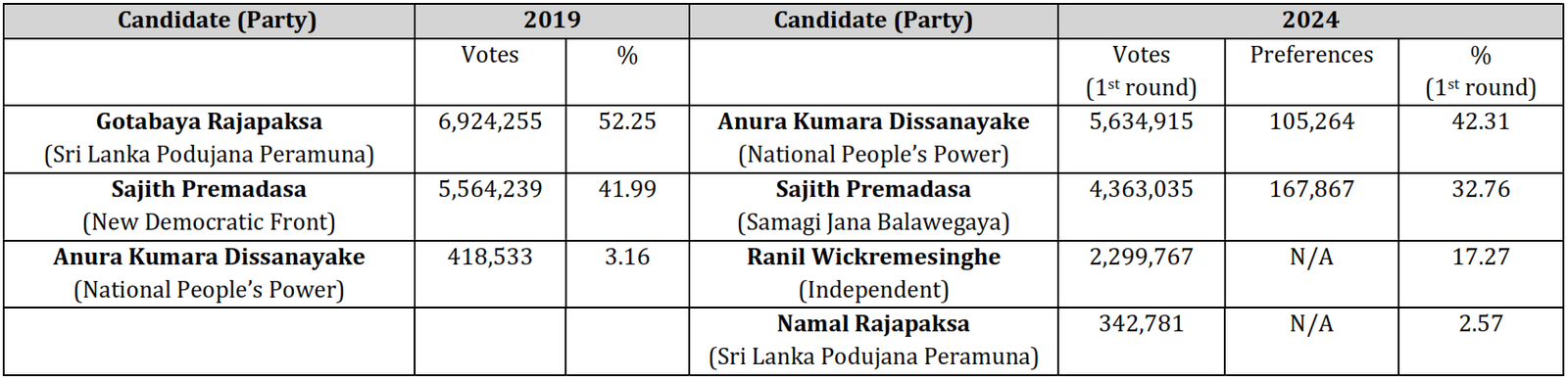

The table below contrasts the results between this presidential election and the one before in 2019. It illustrates the yawning gap between the victor on this occasion, and his rivals five years ago. The scale of Dissanayake’s pole-vault into the presidency; and the ignominious collapse in the vote of the SLPP is highlighted here.

A momentous verdict has been delivered by the people of Sri Lanka. Those who for almost two decades had offered pooja to Mahinda Rajapaksa, turned their backs on his anointed heir and putative leader of his party. Meanwhile Ranil Wickremesinghe, the self-acclaimed author of “stability” and “recovery” and patron saint of the household gas cylinder, was fittingly answered by those whom he fed to the fire. His bête noire Sajith Premadasa offered a pottage called a “social market economy” – except his economic troika’s recipe is torn out of Wickremesinghe’s cookbook made in Washington, D.C. Those who voted for Premadasa, did so for divergent reasons: the rich for continuity of the IMF programme in the anticipated loss of their favourite Wickremesinghe; the middle-class for incremental change in reaction to the red scare around the National People’s Power (NPP); the poor in expectation of the renewal of welfarism, associated with Premadasa père. On the victor, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, millions have pinned their hope of change in the country’s political culture, and thereby its course.

As the dust settles on Sri Lanka’s ninth presidential poll, and we enter a four-week campaign to elect a new parliament on November 14, here are 10 assorted aperçus on the election that was.

I. More the Merrier

A record 39 candidates ran in this election, including two Buddhist monks and a sprinkling of Tamils and Muslims. Local election observers say that anywhere between 13 and 16 among them were proxies. The dummy candidates were canvassing for either Ranil Wickremesinghe or Sajith Premadasa. Some are serial contestants and self-promoters (the businessman and owner of the Sri Lanka Labour Party, A. S. P. Liyanage among them). A few were in it for media and public visibility, with an eye on the general election. As a former presidential candidate, some think they can bargain better with a national party for a parliamentary nomination or national list seat, or a juicy state appointment. All but the top three lost their security deposit (Rs.50,000 or Rs.75,000) for falling short of a minimum of 12.5% of votes cast. The Commissioner General of Elections claimed that “additional” names on the ballot paper increased costs by Rs.200 million each.

II. Missing Women

The 2024 presidential election was an all-male affair. Women are 52% of the citizenry. They won the right to vote in 1931. The world’s first woman head of government was elected in 1960. Her daughter in 1994 became Sri Lanka’s fourth elected president. However, breakthroughs for individual women of a privileged class, have not broken barriers for other women in society and politics. Women in parliament have not exceeded 5.3%. There are even fewer in provincial councils. The quota for women in local government has made a difference; but not yet reached the mandated 25%. What did male politicians offer women qua women in this election? 25% female representation in all elected institutions said Premadasa; 50% countered Dissanayake. A reduction in unpaid care work, said Dissanayake’s manifesto, but nothing on how to get there. A shift of maternity benefits provision from the employer to the state to promote women’s private sector employment, said Premadasa’s manifesto, but no more. Other mentions of women identified the plague of gender-based violence, but without a reassuring response to it. In the manifestos as in budget speeches, women appear mostly as potential units of production: as salaried workers in the formal economy; and as self-employed poultry and dairy farmers, and micro-enterprise operators elsewhere.

III. Political Crossovers

The spectacle of defection of parliamentarians from their party candidate to a rival, supplied the theatre in an otherwise staid campaign. Ranil Wickremesinghe won that beauty pageant hands-down. Around 100 SLPP MPs abandoned their sinking ship for him. It was not, they said in unison, that they loved Mahinda Rajapaksa and his party less; but that they loved their country more. Of almost 30 others, most threw in their lot with Sajith Premadasa; while the remainder regrouped with media mogul and Rajapaksa regime-era propagandist Dilith Jayaweera. The assumption in the Wickremesinghe and Premadasa camps was that the MPs would carry their vote bank with them. Both soon realised that their organic supporters, and undecided voters, were repelled by their sight. The former SLPP MPs were thereafter cloistered, and not to be seen in public. To fortify the SLPP loyalists who remained, Namal Rajapaksa threw his hat in the ring, when the billionaire Dhammika Perera mysteriously withdrew his candidacy. What four years ago was a parliamentary group of about 145 in the 225-member legislature, had shrunk to perhaps 15, and minus their big beasts, bar a couple.

IV. Election Manifestos

Who reads election manifestos in Sri Lanka? Not many it seems. Yet pundits demand policies; and political parties deliver promises, minus a price tag. “Five Triumphant Years for Sri Lanka with Ranil” trumpeted Wickremesinghe’s manifesto, adorned with a commendation from IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva. In a characteristic touch, an elective affinity between free trade and Theravada Buddhism was claimed. Who knew this island’s monarchs of yore were the original globalisers? Premadasa’s manifesto was titled, “A Win For All”. A market economy, leaving no one behind. Rather like a corruption-free administration, run by the corrupt. “Namal’s Vision” (Dekma) was the self-effacing title of Rajapaksa fils offering. He promised to end the slogan of fraud and corruption, so wrongfully attached to his lily-white family. Dissanayake’s 130 page “book”, supplemented by 13 sectoral policy documents, was styled, “A Thriving Nation, A Beautiful Life”. Lots of the same words as the other manifestos; but nowhere “socialism”, nor more importantly, “capitalism” among them. Common to all leading candidates, other than export promotion and green energy, was digitalisation. Monies may be scarce for public investment, but fear not, there is always a digital fix.

V. Mariana Mazzucato

No one mentioned the Italian-born economist by name. But it looks like the kindle edition of the book that made Mazzucato’s reputation has been doing the rounds in Colombo. The Entrepreneurial State was an idea invoked across manifestos. Perhaps most explicitly in Dilith Jayaweera’s corporate board style “National Strategic Plan”. Everyone loves an entrepreneur. Apparently there is something wholesome and good in being one. Somehow in Sri Lanka, “business person” lacks the same qualities: tainted by association with dirty politicians and dirty money. Beyond the “labs”, “hubs”, “innovations” and “ecosystems” that pepper policy conclaves on entrepreneurship, Mazzucato proposes to bring the state back in. She argues that global north economies need the state to take risks and shape markets, to increase their exports and international competitiveness. The manifestos do not expand on what they mean in speaking of the entrepreneurial state. But they recite it, as it sounds like a “win-win”. A partnership between a virtuous market actor that creates economic value; and a legitimate role in market capitalism for those who manage the state, incidentally the creator of wealth for officials and their cronies.

VI. Fathers and Sons

There were two sons of ex-presidents in this race. They had to grapple with the same dilemma. How to forge one’s own path, distinct from that of one’s politically successful father; while profiting as much as possible from thaththa’s electoral capital? Both started off wanting to be their own man. For Sajith Premadasa it was about his schools’ programme, where buses were donated and classroom smart boards installed. For Namal Rajapaksa it was about making himself the face of youth and their aspirations – which apparently is how to become rich quickly. However, as the campaign progressed and the enthusiasm of the crowds flagged, both rebranded their candidacies. Namal Rajapaksa folded his dekma into Mahinda Rajapaksa’s chinthanaya (thought). What his father had initiated: mega-development schemes and high growth rates; Namal would revive. Meanwhile Sajith Premadasa began displaying images of his father, reminding people of the garment factories and jobs Ranasinghe Premadasa brought to the rural economy, of the housing projects and new villages he constructed, and of the Janasaviya (‘people’s strength’) poverty alleviation programme he created. Both sons scrupulously avoided attacks on the other, blasting Dissanayake instead.

VII. Stockholm Syndrome

Why did many urban and rural poor, daily-waged and precarious workers, express support for Ranil Wickremesinghe? The class solidarity between the commercial and socio-political elite and their representative is easy enough to understand. So too the delirium of the middle-class commentariat and right-wing economists and policy wonks for seizing opportunity in the crisis, to push through the latest phase of neoliberalism. But from conversations across the country during the campaign, some of those whose lives and livelihoods were devastated by the austerity policies of his ‘fiscal consolidation’ programme – the withdrawal of subsidies on energy; the increased indirect taxes; social security nets with gaping holes; and the spiralling cost of living – saw him as their redeemer. He had brought political order where there was none; negotiated the talismanic IMF bail-out; and restored normalcy in quotidian functioning. What is masked for most, in the grip of our own version of Stockholm syndrome, is that it is the market fundamentalism advanced by Wickremesinghe and others for more than four decades, that drove us into this woeful situation of an imbalanced economy, sovereign indebtedness, and extreme vulnerability to external shocks, in which we remain.

VIII. Donkeys against Change

Soon after the election result was announced, an electoral map by an NPP supporter began circulating on social media. It showed the districts where Dissanayake had not led in the result. These areas neatly map onto districts in the north and east and central provinces where Tamils and Muslims of north-eastern and hill country origin are in the majority. For avoidance of doubt, an icon of a donkey was affixed to these areas. Of course, this inflammatory message was not endorsed by the NPP, and was soon squashed online by its other supporters. However, the message stuck. Dissanayake himself had earlier sparked controversy when in palpable frustration he asked Northern Tamils, why they were not joining the national movement for change. In fact, as many hit back, national minorities have consistently supported the candidate representing an alternative to the venal, Sinhala nationalist, and militaristic Rajapaksa clan, in 2010, 2015, and 2019. On each occasion, it was the Sinhala majority that stood against a break from the past. Incidentally more people in Tamil and Muslim majority Batticaloa voted for Dissanayake, than for the so-called ‘common Tamil candidate’, who hails from that district and was its former member of parliament.

IX. Common Tamil Candidate

There were a handful of Tamil and Muslim candidates of wildly different perspectives in this election. Among them, only Pakkiyaselvam Ariyanethiran – breaking with his party (ITAK–Ilankai Tamil Arasu Katchi) to contest as a ‘common Tamil candidate’ for the north and east – crossed 1% of the popular vote, polling 226,343 votes. This result placed him fifth after Namal Rajapaksa and ahead of Dilith Jayaweera, Sarath Fonseka, and Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe amongst others. Ariyanethiran’s promoters in the Democratic Tamil Nationalist Alliance (DTNA) and related civil society groups, backed by sections of the Tamil diaspora that are pro-LTTE, argued the need for a contestant to call attention within Sri Lanka and abroad to the absence of a political solution to the grievances of Tamils. Many politicised Tamils in the North and East warmed to the campaign; not for its candidate or content, but rather to send a message to their own politicians. They despair of the endless fissures and splits within the Tamil polity, and demand unified and coherent representation.

X. Left Out

Multiple candidates of the Left have been a feature of presidential elections since 1982. On this occasion too, there were five individuals representing parties and ideologies to the left of the NPP. The top three were the former leader of an electricity workers’ union, Priyantha Wickramasinghe of the Nava Sama Samaja Party, with 0.1% (12,760 votes); followed by lawyer Nuwan Bopege of the newly launched People’s Struggle Alliance, with 0.08% (11,191 votes); and veteran candidate Siritunga Jayasuriya of the United Socialist Party, with 0.07% (8,954 votes). In total, the five socialist contestants scored 0.32% or 42,653 votes. This is a new nadir for the non-JVP Left. It says something about the magnitude of the wave (rella) for the NPP. Activists in the workers, peasants, and social movements, who have in the past stood for anti-capitalism and pro-minority politics, decided this time to side with the NPP. The non-militancy of the working class and other sections of the exploited, meant that there was no class and ideological polarisation that might have driven radicals to support these small groups.

The Box and the Street

In our political and economic system, citizens wield their limited authority transiently: as the campaign season opens and until election day closes. In this period, the candidates appeal to citizens to yield their power to them. The citizens – raja sehari (‘king for a day’ as Malays call the bridegroom) – willingly oblige at the ballot box. Thereafter and until the next election, they turn into supplicants of those whom they anoint as their representatives.

Yet, 2024’s turnaround in the electoral fortunes of Sri Lanka’s traditional parties and personalities cannot be accounted for without reference to 2022’s people’s uprising that manifested in public spaces and not in parliament. This ought to be a constant reminder to the rulers and the ruled alike. What is surrendered between elections, and much more, can also be claimed and gained by common folk in their workplaces, their communities, and on the streets.

B. Skanthakumar is an editor of Polity.

Image source: https://bit.ly/3YlUGvl

You May Also Like…

Obeyesekere the Dreamer: Visionary Journeys in Anthropology

Anushka Kahandagamage

I remember vividly one pattern in my youthful dreams repeated time and again, without too much variation, that of...

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...