The Argentinian (2001) and Sri Lankan (2022) Financial Crises: Ways Forward from a Feminist Perspective

Corina Rodriguez

In response to Sri Lanka’s ongoing economic crisis, and the consensus across the political spectrum and even social classes that an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bail-out and structural adjustment programme is the only short-to-medium term exit or at least breathing space for citizens, the Women and Media Collective and the Social Scientists’ Association organised an online talk by Argentinian feminist economist Corina Rodriguez* on 12 April 2022. She discussed similarities and differences between the Argentina and Sri Lanka financial crises of 2001 and 2022 respectively including the role of the IMF, and her perspectives on what needs to be defended during an IMF plan in order to support economic recovery for popular classes. Polity magazine is pleased to publish a lightly edited version of her remarks, transcribed by Treshan Fernando.

It is my pleasure to be here. Thanks so much for inviting me to this conversation. Let me start by expressing my solidarity with all of you. I know what it feels like to be in the middle of this crisis that affects everyone and everyday life. I send you strength to fight and overcome this period.

I thought about organising my talk in three parts. The first one, an introduction. I understand that some people in our discussion today may not be aware of the whole economic picture of the debt issue. So, a very short introduction on the issue of financial crises in the Global South, followed by the experience we had in Argentina with the financial crisis in 2001. And then I will talk about what I think are the similarities and differences with the case of Sri Lanka; and what I think might be the alternative ways forward.

Introduction

My first message would be that this crisis is not an exception. It is part of the dynamic of global financial capitalism, which is the state of capitalism we’re living in, that is characterised by the rationality of finance capital ruling the economy. There are a lot of unregulated capital flows searching for new opportunities to make profit. Debt has a key role in this financial dynamic. This crisis is part of the logic of financial capitalism.

So why do countries in the Global South face these recurrent crises, and what is the fiscal and monetary logic behind this? The issue is that States need money to rule the economy. States need money for current expenses: to pay for social provisions, education, health, social protection, investment in infrastructure, pensions, etc. But also, the State needs money to pay for financial commitments. Debt has become an increasing part of government expenses. There is always a tension between resources allocated to current expenses that allows States to provide for people’s needs and the pressure of financial obligations from debt commitments.

I would also like to highlight that many times—and this is very typical of countries in the Global South—States have difficulty in gathering the resources they need to pay for current expenses but also financial expenses, which has to do with the difficulty of getting money through the tax system. Here, tax abuse by corporations plays a big role. So, this crisis does not come just from governments doing badly, by spending more than what they have, or the consequences of corruption, but also the consequence of corporations’ tax abuse and the whole global tax system that allows corporations to pay much less than what they should pay.

Then the question would be what this financial crisis, in Sri Lanka as in Argentina, has to do with the need for foreign currency. Why do States need foreign currency? They need foreign currency to pay for imports. If you need to buy goods that you are not able to produce in your own country, you need foreign currency to import goods. But you also need foreign currency to pay for financial commitments when they have been committed in foreign currency. That’s the case of external foreign debt. Also, States need foreign currency for corporations that have investments in the country and want to take their profits back to their own country.

So how do States get this foreign currency? The natural way to get this foreign currency, to pay for commitments in foreign currency, would be through a positive trade balance. The country should export as much as possible and the difference between the country’s exports and imports would be the trade balance. When that balance is positive, then you have enough foreign currency to pay for whatever commitments you have in that currency. But you can also get foreign currency from foreign investors, corporations, even other countries that come to your country and make investments.

You can also get foreign currency by borrowing in foreign currency: which is external debt. Here I want to highlight that external debt is not only held by international financial institutions, namely the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), or regional development banks, and governments of other countries. Maybe in the case of Sri Lanka, China played an important role. But you can also go to the bond market where those who provide you the money when you issue bonds and sell them in the market are mostly global investment banks. In the case of bonds, it is important to note that there might also be people who live in Sri Lanka that hold bonds of Sri Lanka’s external debt. This is an important issue, as it was in the case of Argentina, because when your main problem is with debt from the bond market, and you need to renegotiate that, it is very important to know who holds those bonds, and whom do you need to sit with to renegotiate the debt.

Argentina and Sri Lanka

What’s the problem then? Here we come to the concrete experiences of Argentina and Sri Lanka. The problem is that highly dependent economies, that is economies that are too open and depend too much on getting foreign currency to buy imports to attend to people’s needs and to fuel the system of production, are more vulnerable to external and financial shocks. That was the case of Argentina and I guess the case of Sri Lanka as well. We are highly dependent economies: dependent on what happens in the rest of the international economy.

The second problem is also the dependency on foreign investors. The promotion of international foreign investors to invest in our country might be good in the beginning because they might bring money and help build infrastructure that we need for electricity provision, for roads, whatever. But then in the long run they are also a source of demand of foreign currency because they take their profits back to their own country once the investment is finished. So, when the trade balance is too small, foreign currency becomes critical, and that’s when there is an issue. And I think Sri Lanka is facing the same issue that Argentina faced 20 years ago. That was, we were increasingly indebted; the bigger the debt the more expensive it becomes. If you want to get new loans to pay for the loans you already have, then the interest rate they ask you to pay is higher and higher.

So, what happened in Argentina? In the case of Argentina, the first thing that I would like to say is that it was both an economic and political crisis. I think that economic crises are always political crises. It’s important to understand that, because there is a narrative that tries to impose the idea that the debt issue is a very technical issue and that you need to be an expert to understand it. I want to emphasise that the debt is itself a political issue, and the solutions for the debt crisis are also political.

Argentina 2001 Crisis

What were the main features in Argentina in 2001? Just before the crisis, we came through a long period of economic recession. We have an economy that is partially dollarised, in the sense that many key prices of the economy were set in US dollars. The price of energy, the price of economic assets, and even local banks in Argentina were providing bank credit to the private sector nominalised [that is, expressed] in foreign currency (USD). So, we had, and still have, a partially dollarised economy, which is part of the problem.

The economy was going through high fiscal deficit and, because of the specific form of currency management that we had at the time, we had a high demand for foreign currency. One of the characteristics of Argentina is that, in the trade sphere, we have a positive balance. We export more than what we need to import. So, we had a positive trade balance, but still it was insufficient to attend to our foreign currency demands.

We had increasing external debts. At first, it was the IMF that was providing that debt but then Argentina went to the bond market, and we ended up taking debt at a very high interest rate. It was at 16% when the international interest rate was only one percent.

And then, I think like in Sri Lanka, the international reserves at the Central Bank went to their minimum. So, what happened? The situation worsened and there was finally a combination of a social and economic crisis because the economy was performing badly, with very high unemployment and very high poverty rates. It was a social crisis. People were unable to provide for their needs. It was also combined with a fiscal and monetary crisis and with a bank crisis, which I’m not sure is the case in Sri Lanka.

What happened in Argentina was that, at some point, middle class people who had their savings in the banking system were unable to take their money out of the banks. I mention this because this was the basis of something that was very unique in the history of social mobilisation in Argentina, and I think something similar is also happening in Sri Lanka; which was the coming together in protest not only of the working class but also the middle class. It was the middle class who went on the streets to protest. Their main trigger was that they were unable to take their money out of the bank.

So, it was a combination of a social crisis with a bank crisis; and it was also a political crisis in the sense that during the whole period that lasted for a few years until 2001 when it finally exploded, there was an increasing lack of credibility of politicians. When we were protesting in the streets, we were shouting out this phrase in Spanish: que se vayan todos which means something like “go away all of you!” In other words, this movement was not only against the ruling government, but it was against the whole political class. So, the political system was very much in crisis.

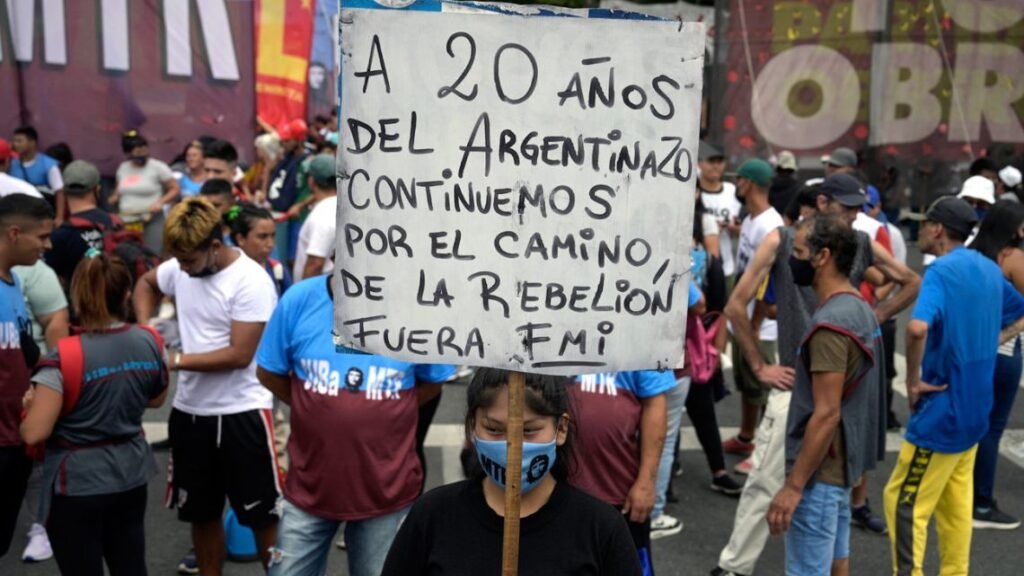

There were massive protests with this characteristic of poor and working class people together with middle class people in the streets for days and days. There were riots, and some people died during these protests. There were also massive street protests. But there was also a mobilisation process in the form of people’s assemblies in neighbourhoods. People got together in open spaces in their neighbourhoods and started to discuss how to handle this crisis together. That also was something that was unique from past social mobilisations in Argentina.

The crisis intensified and finally the government collapsed. I think this is also an important point because it was a different political leader who took up the process of re-negotiating the debt and establishing the basis for the economic recovery. Maybe in Sri Lanka you need to go through this too. I doubt the same government that took the country into this crisis, can be the one to overcome it.

In the case of Argentina, the government collapsed. The President had to flee his official residence and there was more than a week of anarchy. Finally, the Parliament elected a new President who was the leader of the majority political party in Argentina; the same that was in government but from a different part of the party. This person led the process of deciding what to do with the debt and, after that, established the basis for recovery.

So, what happened in the case of Argentina, and apparently this will be the same in Sri Lanka as per today’s news, was that Argentina decided to default and restructure its public debt with bond-holders. Argentina did not default with the IMF but only with bond-holders. But unlike in Sri Lanka, as far as I understand, the IMF was not supporting the Argentinian government. So, the negotiation was between the Argentinian government and the representatives of those who held the bonds of the debt.

But one interesting point in the Argentinian case was that those who were buying the Argentinian external debt issued in bonds were the investment funds who managed the national pension system. Argentina during the 1990s had gone through structural adjustment programmes. Consequently it privatised the national pension system, which became a system where what you contribute goes to your individual account and then when you’re retired, you get that money. These investment funds were managing those savings accounts within the pension system.

This is also unique, and I guess it’s different in the case of Sri Lanka. What I’m trying to say is that in the case of Argentina, debt restructuring was possible by seating, may be 10 people around the table and discussing with them, because there was a concentration of those who were holding the bonds on which Argentina was defaulting.

The four main steps to stop the crisis were firstly, defaulting and restructuring of the public debt with bond-holders, not with the IMF. The second was the devaluation of the currency. After the first big devaluation, there was a plan to stabilise the exchange rate and then the prices. Because there is this risk, in Argentina this is the case, when you devalue the exchange rate, prices go up because we have this dollarised economy. Then, people’s ability to buy what they need goes down. So, it’s important to go through this with a clever plan to stabilise the exchange rate and prices.

The third one, and I think this is very important — and it should be one of the demands in the case of Sri Lanka — a very comprehensive cash transfer programme was established to contain the negative effects of the crisis on the most vulnerable social groups. It was a huge cash transfer programme that really helped people to survive during those times. Then Argentina also went through the de-dollarisation of the economy in terms of transforming the dollar nominated contracts into the local currency, including the ‘pesification’ (our currency is called Peso) of people’s savings in the banks. The savings that were nominalised in the US dollar were turned into the national currency, which meant a big loss for people’s savings, most importantly for the middle class.

Similarities and Differences

To begin concluding my remarks, I’m coming to what I think is similar and different in the case of Sri Lanka. How did we overcome this crisis? How did we establish the basis for recovery, after these four measures were able to stop the crisis from deepening? In Argentina, it was a special moment in the global economy and most of the economic recovery was based on the boom of commodity prices. It was a time when prices of the products that Argentina mostly export, soya and other primary goods, were very high. This was a big source of funding of the recovery in the Argentinian case.

The second thing was that, at some point, Argentina decided that because the economy recovered and because we had this very positive situation in the international market with export revenues, to make a full payment of the stock of the debt to the IMF. So, something that also helped Argentina recover was getting rid of the IMF, not bringing the IMF in. This is something different from what is happening in Sri Lanka.

So, the economy started to recover, and it was also important to have this platform of social protection, and to have a cash programme to support people’s income, and it was the basis for the recovery of consumer demand. There was a slow recovery of employment and people’s income. This social safety net that was established in the emergency of the crisis, became a core part of the social protection system. Until now, we have this very big conditional cash transfer programme that supports people’s income.

Argentina’s crisis exploded at the end of 2001, and by the middle of 2003 the domestic economy was already recovering and growing at very high rates. That had to do, I repeat, mainly because of the international economic situation that favoured the Argentinian economy, which is basically based on exporting primary goods and natural resources.

One of my last points on the Argentinian case is that something that came out of the crisis was a new structure of social organisation. At the time of the crisis, a new social movement appeared, which is that of people who were out of the labour market, who were unemployed, who survived with very small economic initiatives. This part of the population since 2001 started being very much organised in their neighbourhoods, and they kept setting limits on the government as to how much people can stand. When the economic situation starts to deteriorate again, it is very important to have these new social movements, very alert and there in the streets to demand for people’s needs.

The second issue in terms of social mobilising was also the consolidation of a massive feminist movement which peaked in 2015, where we were struggling on sexual and reproductive rights issues and for policies regarding violence against women. In 2015 there were massive feminist mobilisations and the feminist movement became a key and active social actor. The point I like to make is that the feminist movements in Argentina have increasingly included economic issues in their agenda. For example, last year on 8 March, International Women’s Day, the feminist movement went to the streets, and one of the slogans had to do with debt. We had this demand in Spanish which says vivas, libres y desendeudadas nos queremos, which in English would say something like “we want ourselves to be alive, to be free, and to be debt free”. To be free of debt, is one of the demands of the feminist movement nowadays.

I think it is useful to bring new issues up in the debt discussion. The main point would be that, when we are facing a crisis, and thinking about how to overcome it, when you bring a feminist lens, then your priorities change and you think about how to overcome the crisis in a way that people are put first, as a priority. The issue would be how we save people, and support people’s lives, before how we support banks or investment funds. Honouring commitments with banks and investment funds, must come after the commitments that a State or government has to its own citizens.

To finish the story of Argentina, I would say that recovery from that crisis was a kind of success story. The social mobilising that came out of that crisis was a structural change in the type of social mobilising that we have. However, on the negative side, because, during the period of recovery the economy was doing very well, we didn’t go through a change in the development model. We kept on being a dependent economy that basically exports natural resource-based goods and commodities.

Now that the global economic situation is also bad, we are again facing a debt crisis. Argentina in 2018 again went through a financial crisis, not as huge as the one you’re facing now, but it was still a crisis. The government at the time, which was a Right-wing government, decided to go to the IMF and ask for a loan that was the biggest loan the IMF has ever provided to a country. So now Argentina again, has to restructure the debt with the IMF, and we are again in the cycle of dealing with IMF conditionalities and the IMF pushing for a structural change that has much to do with liberalising the economy and organising an economy that is led by the financial logic of capitalism instead of a productive one.

To finish on what I think are the similarities and differences with the Sri Lankan case, I think there are similar economic roots to both crises. That has to do with the dependency of our economies and the rule of financial logic in the global economy. I hope that, as it was in the case of Argentina, this crisis in Sri Lanka can also be a turning point in the sense of a political turn and the possibility of the country deciding to build a different development model. I think the massive non-traditional social protests and mobilisation are also similar in Argentina and Sri Lanka. The youth-led mobilisation in Sri Lanka, I think, is something new for your country, and was similar in Argentina not because it was youth-led but because it was a different kind of social mobilisation.

What I think is different, and makes it more difficult for Sri Lanka to overcome this crisis, is that the Sri Lankan economy is more dependent on imports for basic goods like food or energy. The Argentinian economy was not as dependent on imports so we could go without foreign finance, but still have enough food to provide for people’s needs, and more or less enough energy too.

I understand that Sri Lanka has already decided to default the external debt. In re-negotiations, I am not clear whether you can sit with the people with whom to re-negotiate or whether the bond holders are more dispersed; that might make the re-negotiation more difficult. I think another difference in the case of Sri Lanka is its relationship with the international economy. I bring up the issue of China as a big investor in Sri Lanka, and what the role of China would be in this crisis. We didn’t have that in Argentina.

The other big difference is that in your case, the IMF is apparently willing to help. This can be very risky. Argentina restructured without the IMF. So, we didn’t have to deal with the conditionalities and structural reforms that comes with the IMF. In this case, whoever negotiates in the name of the Sri Lankan people must be very clear about priorities, and about the limits beyond which Sri Lanka shouldn’t accept conditionalities and specific reforms.

I would also raise as a question, whether there is a place in Sri Lanka for an alternative political leadership that can move this negotiation forward and that can establish the basis for a different economic recovery. I think it’s very tricky that the same people who took the country to this situation, are now the ones who are trying to overcome the crisis. My last point on differences with Argentina in 2001, is that the international context is much more difficult now. The whole global economy is going through a very difficult time, and this can also limit the recovery in Sri Lanka.

Conclusion

To close I would emphasise two or three messages. One, this is a political issue. It is not a technical or economic one. It is a political dispute. I think we, and when I say we I mean countries in the Global South, countries that face recurrent debt crises, should find a way to make those who are responsible for the crisis pay for it. I’m not clear about how to do it, but at least it should be very important to make visible the ones who are responsible for the crisis, and why they should be the ones paying for it.

At this point there is no need to think about the cost of defaulting, because you are already defaulting. There is a narrative that defaulting is much worse than trying to pay the debt. I think that is a huge discussion. But you are already defaulting, so maybe this conversation is not needed anymore. I would say that it is important to be very clear about what to negotiate with the IMF; and to be sure that they commit to human rights, and that they do not push for any kind of structural reform or austerity measures that would threaten people’s human rights. So, to push for the human rights framework during negotiations, as difficult as it may be, I think is important.

It could also be key for you to take this situation as a turning point and to think not only about how to handle the debt crisis, how to overcome the crisis itself, but also whether this can be a new beginning for the Sri Lankan economy. That requires a democratic discussion about the development model that the Sri Lankan people want, and one that would make their lives better.

Corina Rodriguez is an Argentinian feminist economist. She works as a researcher at the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (National Council of Scientific and Technical Research) and at the Centro Interdisciplinario para el Estudio de Políticas Públicas (Interdisciplinary Centre for the Study of Public Policy) in Buenos Aires. Corina is a member of Gem-Lac (Grupo de Género y Macroeconomía de América Latina / Latin American Gender and Macroeconomic Group) and a Board member of the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE). Her research interests include Social and Fiscal Policy, Care Economy, Labour Market, Poverty, and Income Distribution.

Image credit: Buenos Aires Times