The ‘Radical Impulse’ in Music in Pre- and Post-Partition India

Sumangala Damodaran

From its second decade, the 20th century saw the need for a people’s art, a need to represent, unearth, popularise, and express through forms that emerged from and belonged to ‘the people’.[1] A whole plethora of ideas and experiments on what people’s music is, should be, and can be, emerged in different parts of the world, fuelled by the need to craft an alternative aesthetic (Donaldson 2011; Eisler 1978; Carruyo 2005; Damodaran 2017). This ‘radical impulse’[2] in art was fuelled by the events of the unique historical conjuncture of the first half of the 20th century and the varied iconography that emerged from the early years of that century to represent ‘the people’ in art and literature (Bowen-Struyk 2001, 2007; Chen 2006).

Nationalist movements in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, the pre- and post-revolution political movements in China and Russia, the Greek Resistance, May 1968, the Civil Rights movement, Popular Frontism, the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and the Nueva Canción (‘new song’) movement in Latin America are some examples of massive political upheavals and movements that created repertoires of political music over the course of the 20th century.

Over the entire 20th century and into the present, expansive and varied notions of “the people” or the “popular classes”, as Gramsci (1971: 19) was to characterise those who emerged as the objects of subjugation, were employed in the creation of protest music. Varied iconographies emerged from the ideologies that constituted the left-wing politics of the time, notably nationalism, anti-fascism, and an emancipatory socialism, and were expressed musically in different ways. Music, like other art forms, came to be employed in establishing the ‘ordinary person’ as a legitimate subject of history and art, resulting in a varied musical iconography of “the people”.

In India, from the 1930s, or the beginning of a transitionary period from colonialism to independence, there was the cultural expression of a very wide range of political sentiments and positions concerning imperialism, fascism, nationalism, and social transformation. An important development in the early 1940s was the formation of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA)[3], a cultural organisation aligned with the left political movement which was set up as an organisation in 1943. This ‘people’s art and theatre’ attempted to reflect and respond to the travails of a colonised nation, as well as to the specifics of the multilayered oppression of the ‘common people’ in the colonial and immediate post-colonial contexts.

Across the country, a large number of the best-known artists of the time became part of the IPTA, attempting to produce alternative aesthetic creations across diverse media. Regional and provincial branches of the IPTA were formed, all engaged in the creation of this alternative aesthetic. In some states, such as Andhra Pradesh and Kerala, other political cultural organisations—the Kerala People’s Arts Club (KPAC, formed in 1951) and the Praja Natya Mandali (PNM, formed in 1948)—emerged, even if a few years later, which aligned themselves with the IPTA.[4]

A significant part of the protest music repertoire in India in the 1930s and 1940s consisted of music that was excavated, retrieved from, and played back to ‘the people’ (Damodaran 2008). This creation of a ‘documentary aesthetic’ was an important component of IPTA’s music which ‘recorded’ the struggles and aspirations of the people and subsequently played them back to society as a means of social mobilisation.

In producing ‘people’s music’ under the aegis of the IPTA tradition, a crucial question that came up was the degree of engagement with ‘tradition’. Within a political understanding that colonialism had destroyed and marginalised the cultures of the people, one of the tasks of musical representation, it was felt, was to ‘bring back’ into the public sphere traditional music on behalf of the people, encompassing indigenous folk music, as well as classical traditions. Musicians had to respond to and contend with conceptualisations of nationalism, where holding up classical traditions became important in representing the people in a nationalist sense, but then having to simultaneously depict exploitative social and class structures through alternative nationalist symbols, involving folkloric revivals.

For example, the classical musician Ravi Shankar and many others produced protest music that was strongly based in the Indian classical music tradition; they also took the position that music intended for a political cause should not compromise on complexity and rigour in its effort to be accessible to large numbers of people (Damodaran 2008). Accessibility needed to be ensured, according to such a view, not by a forced simplicity of form, but by depicting political situations through the music and democratising performance practices and venues of all music, including that which is inspired by the classical tradition.

The repertoire in the 1940s and ’50s also consisted of songs drawing on Western musical traditions. Politically, such music came from the need for a deep internationalism and an alignment of nationalist and socialist sentiments with international movements against fascism, for civil rights, and for socialism. For example, there was the translation and singing of well-known anti-fascist and socialist anthems and songs like the Internationale, the Youth International, La Marseillaise, the Red Army song, and We Shall Overcome in many Indian languages. A second trend was to create compositions, by the musician and composer Salil Chowdhury to begin with and then followed by others, in the harmonic tradition, resulting in a transformed grammar within the Indian song tradition.[5]

From the 1950s, the IPTA’s aesthetic was incorporated into popular cinema in different languages, with music playing a very important role. Working with colloquial usages in language and folk tunes that stemmed from the lives of ordinary people, these films inaugurated an era of socially relevant, yet commercial cinema. In many of these, the ordinary person was the critical protagonist in a newly independent nation that had achieved the desired transition from colonialism, but which was fast reneging on the radical agenda of independence. The IPTA tradition’s music, thus, played an important role in creating a radical imaginary in the arts in India and also provided the background to some of the most diverse trends in Indian popular music from the 1940s. In other words, the radical imaginary and its elements, as explored through music, played a major role in creating a popular imaginary in the country that moved from the realm of political practice into public entertainment genres.

The period from the mid-1980s or thereabouts inaugurated an era that was to throw up important cultural questions that have particularly marked the last three decades in Indian history, of which the communal question and the caste question were crucial. I am focusing on these two because over this period, particularly since the late 1980s, a large corpus of music came to be created, interpreted, and performed around these questions, challenging and at the same time shaping popular sensibilities in different languages and in different parts of the country. Ubiquitously referred to as ‘Mandal-Mandir’ politics, the rise of majoritarian Hindutva on the one hand and the anti-caste movements on the other, along with the waves of communal conflagrations and violence against Dalits over the decades from then on, saw interesting trends in literature and music. In engaging with communal flare ups, the rise of Hindu majoritarianism, and the relationships between people from different religious backgrounds, interrogating the cultural foundations of ‘secular’ India emerged, once again, as a primary concern. Around the same time, the caste question and Dalit assertion became culturally prominent, through literature and music, insisting on the need for an alternative and emancipatory aesthetic.

The anxieties with the post-independence political and developmental trajectory were to consolidate by the late 1960s, and theatre and music would start to strongly reflect the specific problems that were being experienced by ‘the people’ in different parts of the country. By the time a state of internal emergency was declared in 1975, there was already a growing momentum to political musical forms that were being developed. The nation and its constituents, state repression, regional assertion, economic disparities, caste and religious discrimination, communal tensions, and numerous other political concerns were to be articulated and communicated by various kinds of musicians from the mid-1970s onwards.

An important figure representing oppositional music was that of the ‘bard’ or the ‘balladeer’, carrying forth forms that had been experimented with, from older traditional bardic forms from India, from the days of the IPTA. The IPTA, in different regions of the country, had reproduced and re-worked numerous such forms that combined storytelling and song, like shahiri, burrakatha, harikatha and kathaprasangam.

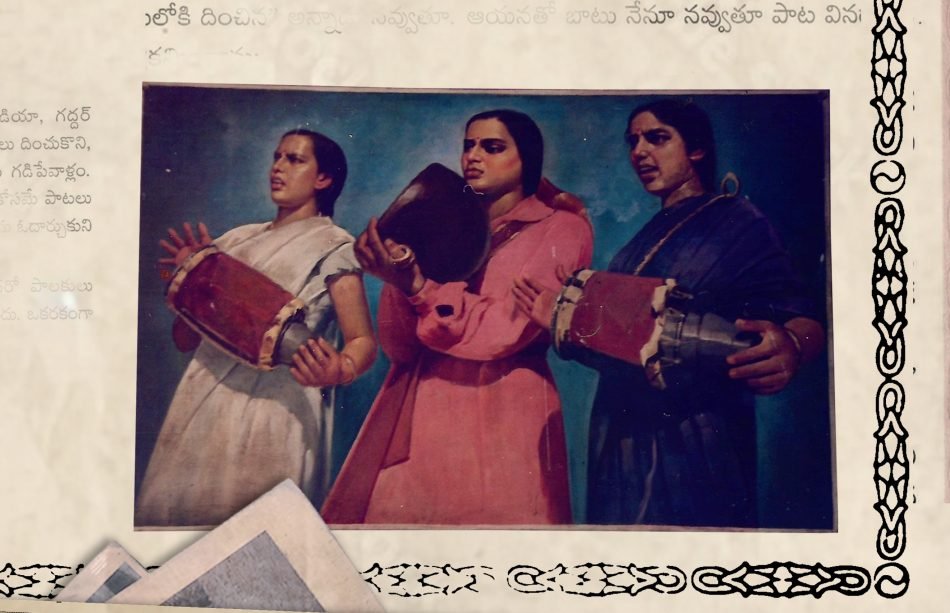

Gummadi Vittal Rao (known as ‘Gaddar’) from Telengana and Sambhaji Bhagat from Maharashtra emerged as prominent balladeers who created vast repertoires of songs on contemporary issues from the 1980s onwards, drawing on long-standing bardic traditions from both the regions. Gaddar, born to a Dalit family from Telangana, worked with the burrakatha (a traditional Telugu storytelling form) and developed it to talk about class and caste exploitation, along with others like the storyteller Nazar, who was one of the best-known exponents of political burrakatha. Traditionally, the burrakatha would consist of stories that contained social commentary and critique, but with artists like Nazar they were used for political purposes, containing scripts with direct political themes and in political fora.

From the mid-1980s, Gaddar actively worked with the Naxalite movement, forming the Jana Natya Mandali, the cultural wing of the People’s War Group, going underground and travelling extensively through forest areas in Telangana in the then Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha, singing and telling stories about the conditions of the people using folk forms. Combining lyrics reflecting what he refers to as a Marxist analysis of conditions in society with the use of traditional folk forms, his songs have taken forward a musical style that developed in the Telugu-speaking regions of Andhra, Telengana, and Rayalaseema from the 1940s onwards, with the formation of the Praja Natya Mandali, affiliated with the Communist Party of India.

Gummadi ‘Gaddar’ Vittal Rao/ Source: bit.ly/4mjE5l9

Narrating the difficulties due to galloping prices during the Emergency, Gaddar sang about how ordinary people found it difficult to eat in a song titled Yemkone Dattuledu (‘There is No Option’). Another song, Ooru Manadira (‘This Village Belongs to Us’) put forward a socialist vision:

Ooru manadira,

Eevurumandira – eevada manadira

Paratipaniki manamra.

Sutti manadi… katti manadi…dorayendiro vadi peekudendiro

(This village belongs to us, these streets belong to us

All work is because of us, all implements due to us

The plough is ours, the sickle is ours

The bullock is ours, the bullock-cart is ours

Who is this oppressor, what is his crime?)

Another example of the ballad style of speech-song being employed to talk about contemporary issues is the Lokshahir tradition from Maharashtra which emerged as the ‘people’s’ version of an old shahiri tradition. The shahirs were medieval poet-singers who travelled across the Marathi-speaking regions singing ballads called powadas about heroism, where dramatic episodes were related through rhythmic metre, and familiar refrains would be combined with colloquial speech-song. Lokshahirs, or people’s poets, like Amar Sheikh, Annabhau Sathe, and D.N. Gavankar, who blazed the trail in the pre-Independence period, explicitly brought the idea of the ‘people’ or ‘lok’ into the shahiri tradition. This breed of firebrand poet-singers, mostly from the Mahar and Mang communities, lent their voices to the independence movement, allied with the communists in movements for social transformation, and later with several socio-political movements such as the one demanding linguistic rights for Maharashtrians and the ‘Free Goa’ Movement. Their organisation, named Lal Bawta Kalapathak (‘Red Flag Artistic Group’), was inspired by Marxist and Ambedkarite philosophy.

In more contemporary times, Sambhaji Bhagat, Sachin Mali, and Sheetal Sathe have emerged as very important lokshahirs who perform music around themes of caste oppression, labour and work, the state, and repression. Bhagat, a Dalit singer who associated with what he refers to as Marxist-Ambedkarite politics, emerged as a major Lokshahir in Maharashtra in the 1980s, providing mentorship to a new generation of musicians like Sheetal Sathe and Sachin Mali in more recent times.

In terms of content, both Bhagat’s and Sathe’s songs, in Marathi and Hindi, contain scathing critiques of caste and class hierarchies in contemporary India:

Inko dhyaan se dekho re bhai

Inki soorat ko pehchano bhai

Inse sambhal ke rehna hai bhai

(Look at these people carefully, brother

Recognise their faces carefully, brother

Beware of these people, brother)

sings Bhagat in Hindi, about those in power who, according to his song, are setter (‘fixers’) and chor-chitter (‘thieves’), warning people in his audience that their oppressors (zaalim) will not be overpowered if they do not call them out by recognising who they are. The oppressors could vary (politicians, people belonging to the upper castes, the police) depending on where the songs are being performed and how audiences interpret it. Bhagat’s target audiences range from people in slums, factories, political formations of various hues of left and democratic politics, universities, and other kinds of settings.

Sambhaji Bhagat/ Source: bit.ly/46gelkG

Interpreting and ‘going back’ to tradition

As has been stated earlier, an important dimension of creating ‘people’s music’ was the engagement with ‘old traditions’. From the 1940s onwards, ranging from classical traditions to folk ones, this had meant a need to contend with varied conceptualisations of nationalism, with musical expressions of nationalism involving experiments with classical and indigenous musical forms in different parts of the world that were about the ‘people’ who constituted the nation and thus offered alternative musical interpretations of the nation.

These questions of how to interpret long-standing classical traditions as well as how to approach folk traditions in representing the people also came up repeatedly in the post-independence period. In the aftermath of the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992, with communal politics and tensions at their apogee, a number of musicians and other artists began to undertake an inquiry into what kinds of music would be able to address the questions that the political situation in the country had thrown up. At the heart of the communal situation were issues of tradition, heritage, nationalism, religion, tolerance, and citizenship.

In Northern India and especially in the city of Delhi, these questions had simmered for a long time, and violent politics had seen the anti-Sikh carnage of 1984, following ‘Operation Bluestar’, and the assassination of the theatre person and cultural activist Safdar Hashmi[6] in 1989, both of which involved the ruling party at the national level. Between 1994 and 2002, a large number of communal conflagrations flared up, with massive Hindu-Muslim riots taking place in Gujarat in 2002, allegedly abetted by the state machinery.

Safdar Hashmi/ Source: bit.ly/4eTT56H

From the 1990s onwards, the inquiry into questions of heritage, tolerance, and rebellion led musicians to begin studying and performing repertoires that were excavated from the past, often from centuries before. Examples that come to mind are the musicians Shubha Mudgal, Dhruv Sangari, Madangopal Singh, the musicians of the Kabir Project[7], to name a few among many who have excavated and worked through various repertoires with a critical view and also many others who have revived traditional, but relatively obscure repertoires from the past. A vast corpus of such music, largely from Sufi and Bhakti traditions from the 12th century onwards, has come to address and re-constellate questions of nation, identity, and politics in a refreshing manner, challenging right-wing cultural assertions frontally, and also shaping popular music listening cultures in the country through contemporary interpretations.

Underlying such excavations into the past were urgent questions: What did Indian history have to offer that would enable the cultural interrogation or interpretation of the present? More specifically, what did older poetic and musical traditions offer that could enable making sense of the present or serve as an alternative to the predilections of the present? What, in centuries old poetic and musical repertoires, could be tapped to tease out secular principles or critiques of the caste system, in order to make appeals for humanism and peace in the present? In sociologist Michael Denning’s (1998) words, what were the elements of the ‘usable past’ that could address the issues in the present?

This alternative musical imaginary, however small it might be in comparison to what more conservative or mainstream musical trends were, had impacted the ‘popular’ realm or the ‘public sphere’ through various kinds of media, performance venues, and festivals that were not merely confined to a niche audience of listeners. It was a combination of the content of the poetry, the historical information about the poets/musicians whose repertoires were being recuperated and interpreted, and what they were responding to in the times that they lived in, along with the performativity of the musicians who were performing it in the present, that was creating the popularity of these repertoires.

The possibility that the singing of Bhakti or Sufi music, ostensibly religious forms, might not be necessarily related to a belief in God or otherwise, is powerful. At the same time, the ways in which images are drawn from both Hinduism and Islam and from mythology, makes the genres a compelling way of engaging with questions of communalism. The art of experiencing devotion, through the aesthetic of the Sufi or Bhakti form, gets utilised, in this case, to open a new discourse on the relationship to tradition that does not necessarily hinge on the belief in God or adherence to ritual and thus poses fundamental questions around secularism and inter-religious relationships.

Sambhaji Bhagat, in an interview with me in 2016, talks about the melding of the concerns of the Lokshahir tradition and Bhimgeet in his repertoire in terms of content, and of a Dalit aesthetic revealed through the form of the songs and the modes of performance. He further explains that this is an alternative aesthetic to the Brahminical one, directly challenging caste hierarchies on the one hand and calling for equality or samyavad on the other. The Sufi genre in his interpretation allows for freedom from convention and tradition and this is a liberating and empowering asset in performance, allowing him to point towards ‘secular’ elements.

The protest music repertoires that have been created and the forms that have been worked with, reproduced, and interpreted demonstrate three objectives: First, against the background of a strident majoritarianism as well as a defensive retreat and reaction of minority communities, the music is a call for transcending the narrowness that competitive communalism invariably induces. Second, it brings into the politics of protest a fresh view of history and tradition, going back several centuries. As part of this, questions of nation and tradition have been re-interrogated using musical and literary material from history. Third, an important objective has been a radical one, to understand and inherit older forms to transform them for contemporaneity.

The Western idiom: Indo-Western music

In the last two decades, there has been a proliferation of bands and individuals that have used ‘modern’ Western forms of songwriting, instrumentation, and presentation to point attention to political issues in different parts of the country. Raising questions of caste, state violence, poverty, unemployment, and several others, these musicians articulate protest on topical issues through music that often combines Indian languages and musical forms with Western performance formats, idioms, instruments, and singing styles, or employ fully Western forms of music in Indian languages.

This Indo-Western idiom has been explored in different ways to address and, in fact, confront caste questions directly. Dhamma Wings, for example, is a Buddhist rock band that attempts to spread Buddha’s and Ambedkar’s teachings through music. In Punjab, a whole new sub-genre of political music called ‘Chamar Rap’ or ‘Chamar Pop’ has come into existence, with searing assertion of Dalit identity being expressed visually and musically through music videos. Represented by singers like Roop Lal Dhir and Ginni Mahi, the songs that they have produced use the images of affluence, masculinity, and vigour to herald the ‘arrival’ on the musical and political scene of people from the lowest castes. These images draw from those within mainstream Punjabi popular music and imbue them with political messages that challenge caste discrimination by often drawing on topical incidents.

Ginni Mahi/ Source: bit.ly/46OvBh3

Bands or individuals that sing politics are also numerous in the North-Eastern States of India. Imphal Talkies and the Howlers, and Daniel Langthasa and his ‘Mr. India’ YouTube channel are two examples among many. Imphal Talkies and the Howlers is a folk-rock band from Manipur, known for singing protest songs about politics, insurgency, human rights issues, and racial attacks in Manipur and across the north-eastern states of India.

What is remarkable about the influence of individuals as well as bands that sing politics employing what I am referring to as Indo-Western formats, is their direct and most often immediate response to political events and their quick dissemination to large youth populations in different parts of the country, making them effective political communicators to youth, often through commercial platforms, or certainly through using forms that appeal to the target audiences very effectively.

Conclusion

I have argued that the trope of ‘people’s music’ is one that can be used to provide a connecting thread between various kinds of political music that have been created over a period of more than seven decades in India, and also one that allows for the link between such music and popular entertainment genres that are also often commercially successful. Broadly, within the rubric of political communication, the genres that musicians work with can be categorised as classical, folk, and Western, with the themes revolving around the idea of the nation, the conditions of ordinary people, exploitation, discrimination based on religion, tribe and caste, state repression, and more. The genres that were worked with, the forms used, and the modes of performance varied between areas, different generations, or specific events.

That the musicians, or groups covered here were in one way or the other producing ‘people’s music’ has meant that their target audiences would involve some conception or the other of ‘the people’. While in some cases, like Gaddar, Sambhaji Bhagat, or the IPTA, the rural peasantry or agricultural and industrial workers would be a very important target audience, the bands that have been discussed would more pointedly target the youth (often specifically Dalit youth), whereas the Sufi-Bhakti music would be performed to mixed audiences, including large numbers of middle-class people. In many cases, while the primary purpose of the musicians has been to target specific audiences for political purposes, they have also expanded their influence to target audiences far larger than their original ones, through the internet and commercialisation. In other words, some kinds of ‘people’s music’ that began as political and hence often targeting specific audiences, have also become commercially successful and part of a wider popular imaginary in the country.

By no means claiming to be exhaustive or even representative of either issues, styles or individuals and groups that produce political music, the attempt has also been to make connections between the creation of a political imaginary through music, and the popular imaginary across several decades in recent Indian history.

Sumangala Damodaran is a scholar of people’s music, who is currently Director, Gender and Economics at the International Development Economics Associates (IDEAS) in New Delhi, and formerly professor of economics at Ambedkar University Delhi.

Lead image source: https://bit.ly/44SbImI

References

Bowen-Struyk, H. (2001). Rethinking Japanese Proletarian Literature [PhD Dissertation]. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Bowen-Struyk, H. (2007). “Proletarian Arts in East Asia”. The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus, 5(4): 1-23.

Carruyo, L. (2005). “La Gaita Zuliana: Music and the politics of protest in Venezuela”. Latin American Perspectives, 32(3): 98-111.

Chen, X. (2006). “Reflections on the Legacy of Tian Han: ‘Proletarian Modernism’ and Its Traditional Roots”. Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, 18(1): 155-215.

Damodaran, S. (2008). “Protest Through Music”. Seminar, Issue 588 (August 2008). Available at https://www.india-seminar.com/2008/588/588_sumangala_damdaran.htm

Damodaran, S. (2014). “Understanding the Relationship Between Art and Social Movements: Towards an Alternative Methodology”. In Wiebke Keim, Ercüment Çelic, Christian Ersche, Veronika Wöhrer (Eds.), Global Knowledge Production in the Social Sciences: Made in Circulation. London: Routledge.

Damodaran, S. (2017). The Radical Impulse – Music in the Tradition of the Indian People’s Theatre Association. New Delhi: Tulika

Damodaran, S. (2025). “Music in Politics, Music as Politics – Understanding Radical Interventions Through ‘People’s Music in India’”. In S. Damodaran, S. Gupta, S. Mitra, and D. Sinha (Eds.), Development, Transformations and the Human Condition: Essays in Honour of Jayati Ghosh. Abingdon & New York: Routledge.

Denning, M. (1998). The cultural front: The laboring of American culture in the twentieth century. London: Verso.

Donaldson. (2011). Music for the people: The folk music revival and American identity, 1930-1970 [Doctoral dissertation]. Vanderbilt University.

Eisler, H. (1978). A Rebel in Music: Selected Writings. Trans. Marjorie Meyer. Editor Manfred Grabs. New York: International Publishers.

Gramsci, A. (2020). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. In Tim Prentki and Nicola Abraham (Eds.), The Applied Theatre Reader (141-142). Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Notes

[1] I have drawn quite a bit from my book (Damodaran 2017) and a chapter published in Damodaran et al. (2025) to make the arguments in this article.

[2] I have used the term ‘radical impulse’ (Damodaran 2017) to refer to a plethora of initiatives, both purely aesthetic and political, that aimed to respond to and represent the times. In doing so, the boundaries of artistic expression were consciously interrogated and pushed towards bringing out multiple interpretations of the idea of the ‘radical’.

[3] The IPTA was formed in 1943 as a response to a cultural upsurge that had happened all over the country from the late 1930s or so, where the arts, through all kinds of media like music, theatre, painting, sculpture, photography and dance, were used to express protest. The initiative to set up the IPTA came from the Communist Party of India under the leadership of its General Secretary, P. C. Joshi, who believed strongly that culture had to be an inseparable part of politics.

[4] I have referred to this set of organisations as the IPTA tradition, which includes the IPTA itself in its national and regional versions, as well as various others like the PNM and the KPAC that aligned themselves with the IPTA.

[5] I have argued (Damodaran 2008, 2014) that the harmonic tradition in the IPTA’s music constituted a major innovation in protest music, where working upon the grammar of the music itself could be considered an act of protest, apart from what the lyrics were trying to convey.

[6] Safdar Hashmi was one of the founders of the street theatre group Jana Natya Manch, founded in 1973. He was assassinated on 1 January 1989 when his group was attacked by armed members of the ruling Congress party, as they were performing a street play in support of the local trade union affiliated to the Centre for Indian Trade Unions, in Sahibabad, Uttar Pradesh, an area bordering Delhi.

[7] The Kabir Project, started in 2003, involves, among a range of activities, a putting together of music from different parts of India that reveals the variety of musical forms that perform the poetry of Kabir.

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...