Sri Lanka’s Pre-Presidential Election Politics: Uncertainty or Turmoil?

Jayadeva Uyangoda

The coming few months have the potential to produce major political changes in Sri Lanka. The presidential election is constitutionally due to be held on a date decided by the Election Commission between 17 September and 16 October. It will certainly mark a crucial moment that will decide who governs the country and in what direction, amidst a continuing economic and social crisis of massive proportions.

The question ‘who will govern Sri Lanka after October’ has assumed significance due to three other reasons as well. Firstly, this will be the first election after the 2022 Aragalaya that marked a citizens’ uprising seeking more democratic and accountable government replacing the rule by the traditional political elites. Secondly, it will be judgement time for Sri Lankan voters to pass their verdict on the present government engaged in implementing an economic reform programme since last year in collaboration with the IMF, with no sensitivity to the unprecedented misery it heaps on the vast majority of the citizens. Thirdly, the election outcome will also show whether Sri Lankan politics has reached a new stage, paving the way for an alternative political leadership to emerge as the country’s new rulers.

Weaponising Uncertainty

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka’s pre-election politics has been unfolding amidst a campaign of uncertainty about the holding of the presidential election due before mid-October. It is a doubt created by the United National Party (UNP), the party headed by President Ranil Wickremesinghe, and is designed to spread confusion among their political opponents as well as the voters. This campaign seems to be driven by the assumption, acceptable to President Wickremesinghe, his UNP, and the business elites who back him, that Wickremesinghe should continue as the country’s president if Sri Lanka were to remain on the path to economic recovery.

According to this view, a shift of political power to an opposition party through elections will jeopardise Sri Lanka’s chances of managing the debt crisis through the austerity-based recovery programme, supported by the IMF. Wickremesinghe and his allies are obviously aware that the austerity programme has already caused much economic and social distress among large segments of voter constituencies. To counter the negative political impact of the growing public discontent, both Wickremesinghe and his party have also been propagating the view that Wickremesinghe is the only political leader in the country who has the knowledge, skills, and capacity to take the country out of the economic crisis. There is also the mythology about Wickremesinghe being spread that he is the only leader around to continue to secure the backing of the IMF, international investors, and the powerful States that are key players in the global economy and politics.

This propaganda implied the claim that in order to continue to keep the country’s future in the ‘safe hands’ of Wickremesinghe, holding of the presidential election would be a risk not worth taking. Economic stability or democracy seems to be the two stark options the Wickremesinghe camp is giving the people to choose from.

The UNP’s narrative of the postponing, by any means possible, the presidential as well as the parliamentary elections is also a ruse to avoid the forthcoming electoral tests which, as all the indications suggest, are most likely to deliver president Wickremesinghe another crushing defeat. Wickremesinghe and his UNP suffered a humiliating electoral rout at the parliamentary election held in 2020, with a mere 2.15% of the total votes cast and just one parliamentary seat. Wickremesinghe, who had been the prime minister from 2015 to 2019, was the sole UNP MP in Parliament, elected in November 2020. He became president in August 2022 by default when Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the then president, was forced to resign from office by the public protest of the Aragalaya.

Being a leader with no popular mandate, or support constituencies outside the Colombo-centric business and social elites, Wickremesinghe has only two contrasting alternatives before him: face another severe punishment by an angry electorate; or avoid the trial by voters by hook or by crook.

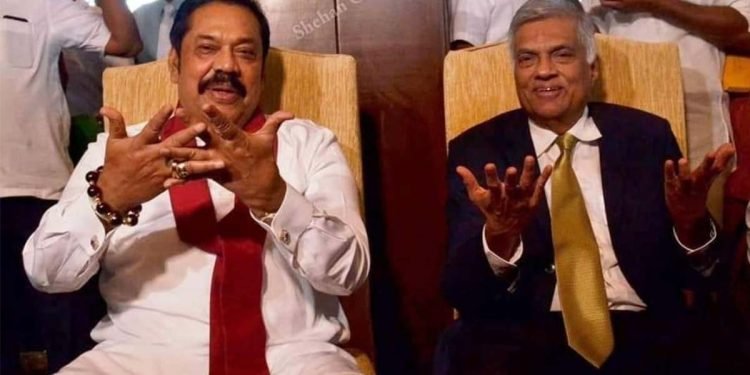

Ranil Wickremesinghe’s anxiety to face the voters this year has very real roots. The coalition he forged in 2022 with the Rajapaksa family and their Sri Lanka Podujana Pakshaya (SLPP) has made it extremely difficult for him to restore any degree of trust and credibility among the masses. Even then, some of the Colombo-based economic, social, and political elites appear to be willing to back Wickremesinghe’s choice for no elections on three grounds. The first is that Wickremesinghe will be able to build a new inter-elite coalition with the capacity to prevent the National People’s Power (NPP), their newest enemy, from coming into power. The second is the fear, increasingly shared among the elites, of the transfer of political power to a broad alliance of non-elite and subordinate social classes by means of a popular mandate. The third is the belief that Wickremesinghe is the only political leader who can, with or without elections, restore the political unity of the old ruling elites which at present remain fragmented and thereby engaging in self-defeating factional fights.

Precarity in the Elite-Mass Relationship

The campaign of uncertainty about the presidential election that the UNP has been promoting also reflects an actual dimension of Sri Lanka’s politics at present. It refers to a continuing state of volatility in the relationship between the political elites and the people. The uncertainty about the electoral process, deliberately engineered by the Wickremesinghe regime, partially reflects a ruling class fear about the people as citizens as well as voters. It is a fear rooted in the Aragalaya of 2022.

The Aragalaya dramatically symbolised a rupture of the traditional elite-masses consensus sustained through the electoral process for decades. Mass protests that forced the then president to leave the country and then the office in July 2022 also demonstrated the presence of a new logic in Sri Lankan politics. Popular trust in the elected leadership and the government had suffered such severe erosion that it required fresh presidential and parliamentary elections as a credible means to restore some semblance of normal politics in the elite-mass relationship. However, avoiding elections to prevent popular anger being expressed in the form of democratic political choices has been a key element of the crisis management strategy of the UNP-SLPP coalition forged in July-August 2022. Thus, in August 2022, they opted for the safe path of a parliamentary vote to get Wickremesinghe elected as the successor president.

Ranil Wickremesinghe’s appointment as president through Parliament, despite its legality, created a new political anomaly, casting a shadow over the legitimacy of the new president and his government. It was a strategic move made by the UNP and SLPP leadership to blunt the political reform potential of the people’s uprising that sought to assert popular sovereignty outside Parliament. The momentary success of the UNP-SLPP intervention could only camouflage the simmering crisis of legitimacy of the Wickremesinghe regime. It was this tension between the popular wish for change in who rules and the old elite’s determination to continue to stay in power ignoring popular pressure that had produced a protracted condition of hidden political volatility in post-Aragalaya Sri Lanka.

Meanwhile, some measure of clarity about the altered balance of political forces of the country could have been achieved had the Ranil Wickremesinghe government allowed the local government elections to take place as scheduled in March 2023. Under the pretext of a shortage of treasury funds to finance a country-wide election, Wickremesinghe coerced the Election Commission to suspend the local government election. The blocking of the democratic electoral process by an unelected president, with the backing of a Parliament that had lost public trust, demonstrated that the old ruling elites were not ready to allow a new political equilibrium to take shape through an uninterrupted democratic process.

Thus, there is a continuing tension between the traditional political elites’ determination to protect the old order and the people’s wish for its replacement under a new political leadership. This tension seems to be the key dynamic that is currently shaping pre-election politics in Sri Lanka. It also has the potential to determine the outcome of both the presidential and parliamentary elections. The presidential election, if held uninterrupted in October, will certainly be the first moment for the peaceful resolution of this contradiction.

Presidential Election’s Outcome

In the absence of reliable data on the trends of the changing public opinion, it is difficult to make credible predictions about the likely outcomes of the next presidential election and a subsequent parliamentary election. However, broad trends in the public mood and the likely electoral choices of the voters can be discerned without much difficulty. Five such interconnected outcomes with crucial political consequences seem to be in order. They are:

- De-installing of the traditional political elites by the voters is a long-awaited, and easily predictable outcome that the presidential election is very likely to set in motion. It is no exaggeration to say that the Sri Lankan voters have been anxiously and silently waiting for an opportunity to punish the dominant elites democratically, and by electoral means. Thus, the presidential election will mark the first moment of judgement and punishment alike.

- Severe electoral setbacks to the UNP, SLPP, and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), the three traditional mainstream parties, are quite in order. These three parties are likely to share the same fate of being reduced to the status of small parties.

- Two opposition formations emerging as the two new leading political parties, one of them even gaining the status of Sri Lanka’s new ruling party, appears to be a new certainty. The Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB, United People’s Force), a relatively new political party formed in 2020 by a large group of UNP dissidents, is the first. The formation of SJB culminated a long-standing revolt against the UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe by a section led by Sajith Premadasa, the UNP’s then deputy leader. The second contender is the Jathika Jana Balawegaya (National People’s Power, NPP), which is a broad front organisation launched by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in 2019 as the party’s electoral arm. Meanwhile, the NPP’s chances of emerging as the winner of the presidential election appear to be improving at the cost of the SJB.

- Even as the SJB and NPP emerge as the two leading political parties, there is no certainty that either of them can win the presidential election with an outright majority (50% of votes cast plus one more vote) in the first count. Neither of the two may even secure a majority of the parliamentary seats (113 or more seats in the 225-member legislature) to form a government on its own. Such an outcome will reflect the fragmented political nature of the Sri Lankan society. In a scenario where there is no first-count winner, the outcome of the presidential election will have to be decided after counting second and third preferential votes. In this scenario, the winner needs to secure only a simple majority, and not the 50% plus one vote requirement, as in the case of a first-round winner. In a fragmented Parliament without a clear winner, return of the old-style coalition bargaining would be unavoidable.

- The contest between the SJB and NPP appears so far to be primarily focussed to win over the votes of the majority Sinhalese community. Therefore, the votes of the three main ethnic minority communities – North-East Tamil, Malaiyaha Tamil, and Muslim – will be crucial to determine the winner of the presidential election. The late realisation of this possibility has compelled both the SJB and NPP to woo Tamil voters by promising them the full implementation of the 13th Amendment. However, Ranil Wickremesinghe has a better political background and credentials to appeal to Tamil and Muslim minority votes than Premadasa or Dissanayake.

Behind this apparent simplicity of the electoral arithmetic are some complex political realities that are certain to shape the election campaigns and the final outcomes. For any presidential candidate representing the three mainstream Sinhalese parties (UNP, SLPP, and SLFP), or an alliance of the three or their factions, regaining lost public trust and legitimacy would be enormously difficult. Arbitrary government, corruption, abuse of political power, and cronyism are not the only reasons why these traditional political elites are facing such a moment of public rejection. Their incapacity and refusal to reform themselves in response to public criticism has made these elites an object of public anger and ridicule too. While the UNP has not been able to recover from the shock of its split in 2020 leading to the formation of SJB, which secured the place of the largest opposition party in Parliament with 54 seats, both the SLPP and SLFP became fragmented in the aftermath of the Aragalaya of 2022. Patronage connections with some constituencies and their loyalty will be the only resources these parties can use to minimise highly damaging electoral setbacks.

SJB-NPP Rivalry

Meanwhile, in a presidential election campaign, the NPP and SJB will emerge as the two principal contenders for power. Candidates representing the UNP, SLPP, SLFP or any other party or an alliance will be minor players, with very little chance of securing even above 10% votes. In the presidential as well as parliamentary elections, the rivalry between the SJB and the NPP will be particularly acute since they will be competing for the votes of more or less identical social constituencies.

Two factors seem to characterise these constituencies for the loyalty of which NPP and the SJB will have a bitter competition. Firstly, most of them have been the supporters and voters of the SLPP at the presidential election of 2019 and the parliamentary election of 2020. After the 2022 crisis, those voters have deserted the Rajapaksa camp en masse. Many anecdotal reports indicate that their electoral loyalties have shifted largely towards the NPP. The SJB is also relying on the possibility of mass conversion of SLPP voters to its side. Yet, a key disadvantage the SJB might not be able to overcome in this competition with NPP for new voters is that the SJB’s leadership lacks either freshness or attraction to young voters, in terms of charisma, generational appeal or the vision for a new beginning.

Meanwhile, the NPP too will face some unique hurdles that have both ideological and electoral dimensions. The political impediments are rooted in the violent political history of the JVP, the party around which the NPP has of late been formed as a broad political movement with moderate and reformist political goals without a radical ideology or a programme. The NPP’s rising popularity among the voters of a broad social spectrum and even the likelihood of it winning the presidential election has sent shivers among all its political opponents: the UNP, the SLPP, the SLFP, the SJB, and other small breakaway groups. There are already signs to suggest that in the highly aggressive campaigns of election propaganda all of these parties will target the NPP in unison bringing back the memories of violence linked to the JVP, particularly during the period of 1987 to 1989. The point which its adversaries have already begun to make is that NPP’s moderate and peaceful image is a mere camouflage, and that in power its true ‘Marxist’ character and policies will re-emerge.

As a defensive gesture, the NPP seems to have been compelled not to give prominence to any policy reform initiative, or an ideological position, that can be construed as ‘too radical’ or hurting the rich. This seems to be the context for the NPP’s lack of enthusiasm to propose at present any innovative social-welfare oriented relief-measures to help the poor, along with tax relief to the middle classes, under its government. However, such defensive tactics can certainly have their own political costs in terms of votes from the NPP’s natural voter constituencies.

Quite interestingly, the huge attraction that the NPP seems to be enjoying among a wide range of social constituencies – the urban and rural poor, working people, middle classes, professional classes, students, women, and the youth – is not because of any specific ideological identity it has built to attract mass support. Contrary to the widespread misunderstanding and misinformation among elite civil society groups, diplomatic communities, and media personnel, the NPP has not been promoting for itself a Left, radical, or even a social-democratic, identity or ideology. Paradoxically, the NPP’s attraction at present is not its radicalism, but its vision and message for change. ‘Change’ (wenasak) seems to be the central trope around which the NPP’s appeal is built and even understood. A wenasak in who governs Sri Lanka seems to be a point that singularly favours the NPP.

What is somewhat unusual for the NPP is that its politics for the past few years since its formation in 2019 has been devoid of any ideological self-labelling as such. In fact, the NPP’s absence of a clearly demarcated ideological identity has coincided with it being projected by the JVP as a broad electoral front with the character of being a ‘catch-all’ movement. Indeed, over the past two-to-three years, the NPP seems to have carefully built a political identity sans conventional ideological commitments associated with the traditional political party system such as Left, Right, Centrist, or Social Democratic.

The SJB’s challenges are also made unusually complicated, primarily due to the lack of a clear-cut ideological commitment or a class identity for the party. It is a party born out of the Right-wing, neo-liberal UNP, the party of the upper layers of the Sinhalese social and business elites. Under the leadership of Sajith Premadasa, the SJB has been trying to re-position itself as a party of the urban and rural poor and the middle classes so that its social bases could be clearly distinguished from that of the UNP. Occasionally, the SJB’s leader has been making the claim that his party has a social democratic vision to look after the poorer sections of society, particularly those who have been neglected by the free-market reform policies of the UNP-SLPP government. However, the SJB is also torn between two opposing economic policy perspectives – social-democratic or social-market middle path of Sajith Premadasa, the party leader, and the free-market, neo-liberal reformism of the party’s team of economists.

What seems to be clear is that both the NPP and SJB seem to be maintaining an openness, if not a policy ambiguity, with regard to the larger policy challenge of addressing Sri Lanka’s on-going debt crisis and the arrangements that the Wickremesinghe government has already made with the IMF as well as external debtors. Given the enormity of the challenge of managing Sri Lanka’s debt crisis and the larger economic crisis, and the unavailability of alternative policy options, exercising caution seems to be the preferred stance of both parties. Caution is also helpful to prevent the excessively harmful politicisation of the most difficult policy challenge, the beneficiary of which would invariably be those sections of the ruling elite that are waiting for excuses to prevent presidential and/or parliamentary elections from being held.

Two Contrasting Scenarios

Amidst continuing uncertainties about the ways in which Sri Lanka’s politics might evolve through the coming three months, two different scenarios with contrasting consequences can be outlined. The first is the prevention of the presidential election being held on a date that fall between 17 September and 16 October, this year. The second is the holding of the presidential election leading to the election of a new president from either the NPP or the SJB – and the formation of a new government by the new president.

Of the two scenarios, not holding the presidential election is entirely a politically motivated executive action designed to serve the partisan interests of those in power, but with no constitutional validity. However, to secure a veneer of constitutionality for such a move, the government might seek judicial intervention to interpret in its favour a legal ambiguity found in Article 83(b) of the Constitution. While Article 30(2) (as amended by the 19th Amendment) reduced the term of office of president from six to five years, a subsequent article on the approval of certain Bills at a referendum, Article 83 left the reference to the six-year term of the president unaltered. It is hard to expect Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court to endorse the government’s utterly partisan reading of a major constitutional provision.

Even then, driven by desperation to avoid a defeat at the election, the Wickremesinghe camp has the option of resorting to some executive-administrative manipulation to postpone the presidential election, as it did to subvert the local government election last year. Such a blatant violation of the constitutional and democratic principles by an ambitious president and his government, if it happens at all, will run the risk of triggering immediate and angry public protests of massive proportions, reminiscent of the Aragalaya of 2022. If the government decides to respond to popular protests by repressive measures, an open confrontation between the angry citizens and a ruling elite determined to protect its immediate political interests might have the potential to be violent, leading to much bloodshed and pain, dragging the country into a protracted phase of turmoil.

In the second and perhaps the most optimistic scenario, a peacefully held presidential election will lead to an immediate change of the country’s political leadership, with a new president elected through popular vote. Such an elected president will command a great measure of public trust and political legitimacy. Against such a backdrop, the new president will carry on his shoulders a huge load of public expectations to clean up and re-build the country’s politics and public life. The new president will also inherit a few burdens the political and social weight of which might keep under check the new government’s agenda for rapid improvement of the conditions of people’s lives for some time. Settling of foreign debts amounting to 37 billion USD over a period of several years, under agreements the terms of which have been determined with no inputs whatsoever from the incoming president, will be a major millstone to carry throughout the new president’s term of office.

Similarly, the new president and his government will also inherit a society and polity devastated by (a) many years of corrupt and inefficient governance, and (b) two years of economic and social destruction under a hyper accelerated process of neo-liberalisation through legal and policy reforms. It is also a society in which (a) the gap between the haves and have-nots has increased dramatically during the past three to four years, and (b) the ruling class arrogance and insensitivity to the social suffering of the have-nots is being viewed as the new normal and also a mark of smart government. It is indeed a polity in which a severely battered State has been hollowed out from society while its social obligations to citizens are degraded to such an extent that both the State and the public sector await a rapid process of repair and re-building under a new pro-poor administration.

06.07.2024

Jayadeva Uyangoda is Emeritus Professor of Political Science at the University of Colombo and editor of Democracy and Democratization in Sri Lanka: Paths, Trends and Imaginations (2 Vols.) (Vijitha Yapa Publications, Colombo, 2023).

Image Source: https://bit.ly/4cWUAPa

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...