South Asia in the New Global Debt Crisis – A Call for Collective Solutions

Amali Wedagedara

Debt payments of developing countries exceed their national revenue. According to a new report, Resolving The Worst Ever Global Debt Crisis, 118 developing countries are experiencing debt distress, with a disproportionate share of their national revenue directed towards debt servicing in 2024 (Martin and Waddock 2024). Thirty-one countries have either defaulted or have access to external financing suspended due to high debt levels. Even though external debt is crippling economies in the Global South, neither the financial and economic reform policies (structural reforms) advocated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB) nor the developing countries as a geo-political bloc have responded adequately to address the crisis at hand. The structural reforms advocated by the IMF and the WB are counterproductive. Furthermore, isolated responses of the developing countries to their respective debt crises have impeded a collaborative and coordinated strategy to hold international financial institutions like the IMF and the WB responsible. These responses have also failed to address the escalation of debt distress in developing countries following interest rate hikes in the United States (US) and the European Union (EU) following the Ukraine-Russia war and the COVID19 pandemic, which may be termed ‘the new debt crisis’.

The absence of an informed collective response vis-à-vis the external debt problem is more palpable in South Asia compared to Latin America or Africa. This article is a preliminary attempt to bridge the gap by analysing South Asia’s debt crisis. While contextualising the new debt crisis affecting South Asian countries, I argue that cultural explanations of the debt crisis of developing countries, undermining the political economy dimension of corruption, have not just diverted our attention away from addressing the structural weaknesses of the South Asian economies, making us accept poison as medicine. They have also stopped us from holding the IMF and the WB responsible for failing to ensure the stability of the global financial order, particularly in the interests of developing countries.

External Debt Profile of South Asia

Spillovers of the global to the local, alias the ‘new debt crisis’, are also evident in South Asia. Following Sri Lanka’s default on its external debt in April 2022, the IMF reported that Pakistan and the Maldives were in high debt distress, signalling that their public debt levels were unsustainable. In addition, both Nepal and Bangladesh sought financial assistance from the IMF in 2022 and 2023 to address their balance-of-payment needs.

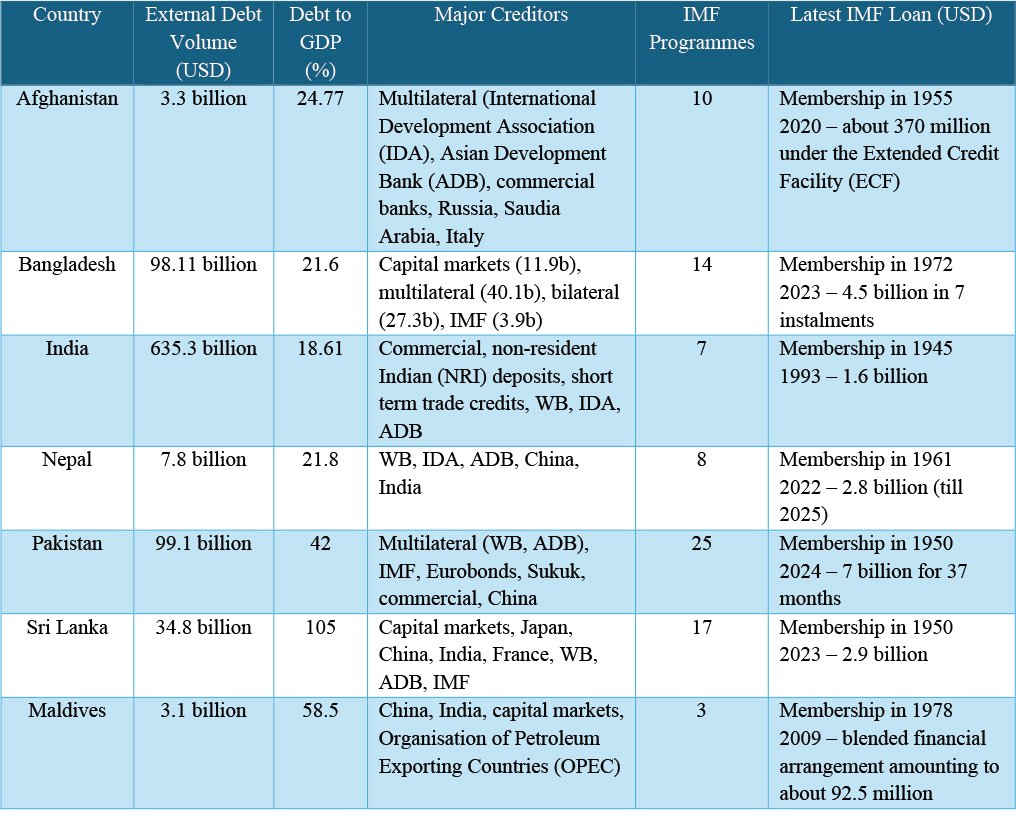

A comparison of the external debt profiles of South Asian countries in Table 1 suggests a correlation between the regularity of engagements with the IMF and the degree of debt distress. Except for Maldives, India, and Nepal, all the other South Asian countries have engaged the IMF more than ten times. While Pakistan leads with 25 engagements with the IMF, Sri Lanka ranks second with 17 rounds. Incidences of interactions with the IMF insinuate the extent of the transformation of national, political, and economic regimes after the structural adjustment reforms that the IMF and the WB promote. Instead of pro-growth policies aligned with local interests, developing countries are compelled to adopt the free market economic model catering to the interests of global capital. With time, productive sectors of the national economies, in manufacturing and agriculture, dissipate by limiting the economy to low-end primary exports. They borrow heavily to finance essential imports, including basic food needs. Consequently, financial dependency, fiscal austerity, chronic balance of payments crises, inequality, and poverty are permanent characteristics of these economies. Instead of exiting the vicious cycle of dependency and crises, the policy orthodoxy of the IMF and the WB has retained these countries within their grip.

Table 1: External Debt Profile – South Asia

Source: IMF, Ministries of Finance (respective countries)

Source: IMF, Ministries of Finance (respective countries)

Structural adjustments accompanied by austerity policies, the ‘bitter medicine’ that the IMF and the WB advocate for countries grappling with economic hardships, have become poison to developing countries worldwide, making them debt-dependent (Fischer and Storm 2023). Even though a minority of financial and political elites benefit, others in the productive economy, such as women, peasant farmers, fishers, small and medium entrepreneurs, manufacturers, and industrialists, do not. Often, they incur losses from the liberalisation of trade, capital, labour, and land markets, the deregulation of environmental laws, and the dismantling of state-owned enterprises and public services such as education, health, and social security.

Budget deficits, fragile currencies, declining government revenue as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), heavy reliance on capital markets, and corruption could be attributed to the reforms that the IMF and the WB advocated over the years (over 17 and 25 rounds of engagements in case of Sri Lanka and Pakistan respectively). However, the economic failure of these countries continues to be explained by cultural factors attributed to poor developing countries such as corruption, nepotism, and mismanagement, ascribing a sense of superiority to advanced capitalist countries in the Global North.

For example, post-default economic reforms in Sri Lanka, as advocated by the IMF and the WB, demonstrated zero reflection on the economic policies practised over 45 years since the liberalisation of the economy in 1977. There is a revolving door linking deregulation and restructuring policies and corruption – the close nexus between the political and economic elites has meant that deregulation and restructuring abet private profiteering. Even though the political elites concur with the IMF and the WB in enacting structural reforms and embracing good governance, neither party have extended their interest to explore the illegitimacy of public debt due to corruption or illicit financial flows. Trade unions in Sri Lanka pointed out an estimated 40 billion USD was lost to the national economy between 2009 and 2018 due to illegal financial flows linked to trade and offshore accounts (Arulingam, 2023).

Austerity policies – cutting down government expenses (budget) forces governments to pursue short-term spending plans instead of designing development in the long run. Budget cuts not only neglect to tend to long-term effects from economic crises on women, children, peasant farmers, and other working people, thereby delaying the return to normalcy – ‘pre-crisis conditions of living’ – but also exacerbate the vulnerabilities. Ortiz and Cummins (2022), studying the impact of austerity policies for over a decade, document the deteriorating conditions of social security, education, and health of the people, increasing violence against women. Public sector reforms aligned with fiscal consolidation policies slash jobs for women more than men. As in Sri Lanka, Kenya, and Bangladesh in recent times, social unrest, tensions, and upheavals have been directly attributed to austerity policies.

Budget cuts create debtors’ prisons. Rather than prioritising productive investments needed to break free from the debt trap, short-termism built into austerity policies compels governments to honour debt servicing, often through new loans. Developing countries unable to pursue planning and restructuring the economies to graduate from low-end export products due to limited fiscal space have experienced lost decades in development. As the small- and medium-scale enterprises, agriculture, fisheries, dairy, and manufacturing sectors representing the productive economy tumble, working people in these sectors lose their livelihoods and incomes. An increasing share of foreign debt, denominated in foreign currencies, wields pressure on dwindling government revenue.

Debt Service Watch 2024 covering external and domestic debt service obligations of 145 countries ranks Sri Lanka and Pakistan second and third place, with Egypt first in the rankings of countries with the highest debt service/ revenue burdens in 2024 (Martin and Waddock 2024). Total debt service as a share of government revenue in Sri Lanka is 202%, and 189% in Pakistan. Bangladesh ranks tenth with 102%. India and Maldives are featured in 25th and 29th place, with 64% and 62% share, respectively. Calculating foreign debt service as a share of gross foreign exchange earnings of these governments will paint a darker picture of the debt sustainability even in the intermediate term.

In addition, high debt distress also corresponds with accessing capital markets. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Maldives have sourced development finance through international sovereign bonds (ISBs) sold to bondholders such as BlackRock, JPMorgan, and HSBC in the capital markets. The high volume of debt owed to commercial lenders, a distinct feature of the debt crisis affecting developing countries, is associated with the policy of financial de-risking by pursuing blended finance promoted by multilateral lenders such as the WB and the EU. Reductions in institutional funds allocated to development projects were expected to be chipped in with private finance, blending multilateral aid and loans with private finance and dispersing the risk. However, the theory of financial de-risking was proven false when private creditors “pull[ed] out US$185 billion more in principal repayments than they disbursed in loans” (World Bank 2023: X) after the interest rate hike in the US and EU in 2021.

The inherent implications of the crisis-instigating policies are concealed under the much-hyped hearsay on debt-trap diplomacy linked to Chinese loans. The real debt trap is in the IMF-WB loans, which impose structural reforms that deny development and the policy-making autonomy of developing countries, and high-interest ISBs issued by private bondholders in capital markets prioritising debt extraction over development.

Straitjacket Responses to the New Debt Crisis

The International Debt Report 2023, published by the WB, documented a debt crisis of an unprecedented scale. Eighteen developing countries have defaulted since 2021, surpassing the number of defaults over the last two decades. Twenty-four countries eligible to borrow from the International Development Association (IDA), the lending arm of the World Bank to low-income countries on concessional terms, are reported as high debt distressed, while 11 others are listed as debt distressed. The same report indicates that debt has become a “paralysing burden” (World Bank 2023: IX), making servicing debt difficult in 2023. Three South Asian countries are undergoing debt crises, with Bangladesh and Nepal in an IMF programme along with Sri Lanka. Taking the volume of external debt or debt to GDP as an indicator of the debt crisis, one may wonder how Maldives, with a little over 3 billion USD debt volume, ended up in debt distress. How so many countries undergo debt crises can only be explained if we look at the problem vis-à-vis several developments since 2021, that is: 1. the interest rate hike in the US and EU in 2021; 2. the COVID19 pandemic (2021-2022); and 3. the Russia-Ukraine war. It is impossible to understand the current debt crisis without putting it in perspective of these global developments.

- Interest rate hikes in the US and EU in 2021: The US Federal Reserve reduced interest rates to 0% to tackle the global financial crisis in 2008. Lower interest rates were expected to make managing and refinancing public debt in Global North countries easier while keeping the financial markets afloat. Low interest rates made developing countries that would otherwise have avoided capital markets (due to high interest rates) borrow from them at an unprecedented scale. Countries like Sri Lanka, disqualified from concessional borrowings after graduating into the middle-income countries category, had to turn to capital markets to source their external financial needs. Sri Lanka borrowed 17 billion USD from capital markets between 2007 and 2019 at 5-8%. In 2021, the US Federal Reserves and EU Central Bank increased interest rates by 4-5%. With the US dollar’s value appreciating, investors repatriated their capital to countries in the Global North. Amidst capital flight from the Global South, developing countries had to incur extremely high costs to refinance their loans. For example, Zambia and Egypt paid coupon rates as high as 26% (they borrowed at 6-8%).

- COVID19 pandemic (2020-1): The COVID19 pandemic brought the world economy to a standstill. It was particularly hard for developing countries that were excessively dependent on tourism, remittances, and primary and low-end exports to source foreign exchange needed to finance essential imports and service dollar-denominated foreign debts. For example, the tourism sector in Sri Lanka encountered a hard blow too soon after the Easter Sunday bombings in 2019. On top of declining foreign remittances, Sri Lanka also lost 24% of its export revenue. The Maldivian economy, which heavily depends on the tourism sector, has contracted by 33.5% (Asian Development Bank 2022).

- Russia-Ukraine war (2023): Speculations around the sanctions on Russia and disruptions to global supply chains against the backdrop of the Ukraine-Russia war led to price hikes in oil, food grains, and fertiliser, which affected developing countries by drastically increasing their import costs (Ghosh 2022).

Overlapping emergencies like the COVID19 pandemic and Ukraine-Russia war at a global scale, along with the interest rate hikes in the US and EU, have created systemic shocks destabilising economies of developing countries like Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Maldives, and other countries in debt distress in the Global South. As a result, the cost of debt refinancing has multiplied, pushing some countries like Sri Lanka, Zambia, Ghana, and Suriname to default. The impact of these external causes on debt distress is more significant than internal causes. However, responses from the IMF and the WB do not reflect a cognisance of the new nature of the debt crisis. Instead of factoring in the impact of these external shocks and enacting their responsibility to create a mechanism to smoothen the vulnerabilities aggravated by these external shocks, the IMF and the WB blame developing countries and impose harsher structural reforms.

There is a clear gap in understanding the crisis and its scale, as manifested in the interests of the international financial institutions (IFIs) and interventions that developing countries need. Economic reforms such as deregulating capital markets and exchange rates, privatising state-owned enterprises, and reducing government expenditure on public services will only deteriorate the structural vulnerability of developing countries. Not only are these reforms incompetent in tackling the problems trickling down from developments in the global North explained above, but they also suggest that developing countries should bear the burden of problems created by policy-making in the global North.

Collaborated and Coordinated Action against Debt in South Asia?

Against the backdrop of the Asian financial crisis in 1997, Asian countries affected by the crisis, like Thailand, Malaysia, and Japan, proposed a mutual supporting system, an Asian Monetary Fund (AMF), to ensure “domestic, regional, and Asian strength, not necessarily to compete but to have a buffer zone” (Takahashi 2023). Even though the AMF never saw the light of the day due to strong opposition from the US and the lack of commitment from China, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), in the Chiang Mai Initiative, has moved along critical ideas behind the AMF (Takahashi 2023). Jubilee 2000 was another instance when developing countries gathered to demand debt justice. Social movements of working people, peasants, women, students, environmental activists, and academics have underscored the dangerous consequences of IMF and WB policies and have advocated reforms for a long time (e.g., the World Social Forum, the La Via Campesina, the Bretton Woods Project, the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt). Thomas Sankara, the former President of Burkina Faso (assassinated in 1987), outlining the predatory and imperialist nature of debt, called for a united front against debt (Sankara 2018).

The urgency of developing countries coming together to propose collective solutions to the new debt crisis while holding international financial institutions accountable is evident. However, the IMF and the WB are using their mediation to tighten their grip over indebted countries. Rather than encouraging indebted countries to pursue collective solutions, IMF-WB intervention has only trapped them in structural reforms and debt restructuring processes that favour the creditors. Argentina, a long-time client of the IMF, is experiencing recurrent debt crises and has repeatedly been subjected to debt restructuring, manifesting the destiny of countries following the IMF route.

Debt crises, debt distress, and defaults have systemic impacts. People’s livelihoods are decimated. Economies regress years into the past. Women, children, and other vulnerable people assume a disproportionate burden. Working people are made to pay more in the process of economic recovery. The overwhelming impact of economic crises indicates that such crises should not reoccur. However, ensuring that debt crises are a thing of the past demands innovative interventions rather than structural reforms and debt restructuring favourable to creditors. The ‘United Front Against Debt’ and ‘Global South Alliances for Development’ will empower developing countries and enable a collective vision to transcend debt distress.

Amali Wedagedara (PhD, Hawai‘i) is a feminist political economist and a senior researcher at the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies (BCIS).

Image source: https://bit.ly/4fG6saC

References

Arulingam, Swasthika. (2023). “Misleading responses by CBSL Governor, JAAF, TEA and Rohan Masakorala on illegal foreign exchange transfers”. DailyFT (23 January). Available at https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Misleading-responses-by-CBSL-Governor-JAAF-TEA-and-Rohan-Masakorala-on-illegal-foreign-exchange-transfers/14-744432

Asian Development Bank. (2022). “BML Supporting Recovery of the Small and Medium Enterprise and Blue Economy Tourism Sector Project: Report and Recommendation of the President”. Available at https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/mld-55156-001-rrp

Fischer, Andrew M. and Servaas Storm. (2023). “The Return of Debt Crisis in Developing Countries: Shifting or Maintaining Dominant Development Paradigms?” Development and Change, 54(5): 954-993.

Ghosh, Jayati. (2022). “Putin’s War Is Damaging the Developing World”. Project Syndicate (11 March). Available at https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/ukraine-war-economic-damage-for-developing-countries-by-jayati-ghosh-2022-03

Martin, Matthew and David Waddock. (2024). Resolving the Worst Ever Global Debt Crisis: Time for a Nordic Initiative? Oslo: Norwegian Church Aid. Available at https://www.kirkensnodhjelp.no/contentassets/c1403acd5da84d39a120090004899173/report_summary_newdebtcrisis_digital.pdf

Ortiz, Isabel and Matthew Cummins. (2022). End Austerity: A Global Report on Budget Cuts and Harmful Social Reforms in 2022-25. Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD), Global Social Justice (GSJ), International Confederation of Trade Unions (ICTU), Public Services International (PSI), ActionAid International, Arab Watch Coalition, Bretton Woods Project, Eurodad, Financial Transparency Coalition, Latindadd, Third World Network (TWN), and Wemos. Available at https://publicservices.international/resources/publications/end-austerity-a-global-report-on-budget-cuts-and-harmful-social-reforms-in-2022-25?id=13501&lang=en

Sankara, Thomas. (2018). “A United Front Against Debt (1987).” Viewpoint Magazine (01 February). Available at https://viewpointmag.com/2018/02/01/united-front-debt-1987/

Takahashi, Toru. (2023). “Asian Monetary Fund Idea Revived amid U.S.-China Row.” Nikkei Asia (20 April). Available at https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Asian-Monetary-Fund-idea-revived-amid-U.S.-China-row

World Bank. (2023). International Debt Report 2023. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/02225002-395f-464a-8e13-2acfca05e8f0