Man in the Mirror

Ruben Thurairajah

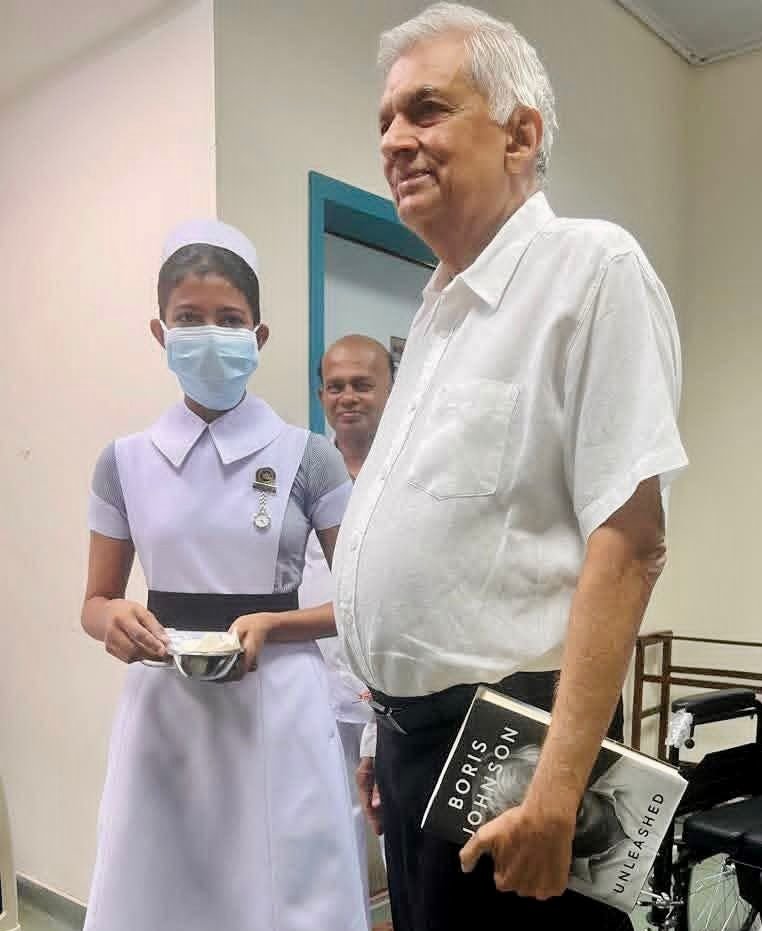

The photograph came first. Ranil Wickremesinghe walks out of the intensive care unit of Colombo’s National Hospital, a thin smile on his lips, a book raised just high enough for its title to be captured by Harin Fernando’s phone-camera. Unleashed by Boris Johnson, ex-prime minister of the United Kingdom. The cover gleamed, the message unmistakable. It was not an accident. It was theatre.

Ranil wanted to be seen as the political intellectual, the elder statesman who endures and reads the wisdom of another statesman, while in confinement. Yet in that choice of prop, he revealed more than he intended. For in Boris’s evasive memoirs, Ranil might have found not only inspiration but also reflection.

The old boys

Both men are children of pedigree. Boris was bred at Eton College, England’s finishing school for its ruling caste, where the air of entitlement came as naturally as Latin tags. Ranil was polished at Colombo’s Royal College, the local imitation of that elite tradition. The two institutions are separated by oceans but united by spirit. They teach their boys not only mathematics and their version of history but the bearing of rulers: the casual entitlement, the confidence that power is a birthright, the conviction that defeat is never final, only temporary exile until the club calls one back.

Boris parlayed this into a career as a journalist-turned-politician, the clownish Etonian whose jokes in Latin masked calculation. Ranil, for decades, parlayed it into the longer theatre of parliamentary survival; losing elections, returning, losing again, always remaining somehow indispensable. The public might vote him out, his party might reduce itself to a single seat, but the old-boy network never allows its chosen sons to vanish.

Proroguing the people

In 2019, Boris, cornered in the House of Commons, tried to prorogue it. He sought to shut down debate, to suffocate scrutiny. It was ruled unlawful by the Supreme Court, but his instinct was clear: when in peril, silence opposition.

Ranil’s version came in 2022. The Aragalaya had erupted; the tents at Galle Face, the hunger queues, the fury of the middle class pushed into poverty. Pensioners collapsed in fuel queues. University students, monks, nuns, marched to Colombo to demand change. Ranil the consummate networker manoeuvred himself on the back of the Aragalaya, to make himself the saviour, president of Sri Lanka.

Once he got his hands on the lever of power, Ranil did not prorogue parliament; he prorogued the street. The tents were torn down, the chants broken, the crowds scattered by batons and boots. Both moves were justified as defence of order, as the safeguarding of institutions, as saving democracy. In truth, both were nothing more than the safeguarding of the man.

Virtues and hypocrisies

In 2022, when his private library was torched during the protests, Ranil presented himself as a victim of barbarism. A bereaved philosopher king. He spoke of the loss of books, the violence against culture. But his own political class, the government of 1981, of which he was a rising star, had presided over the burning of the Jaffna Public Library. Ninety-seven thousand volumes incinerated, memory erased. No speeches then. No mourning. Just drunkenness of power and good old book-burning.

The pattern of hypocrisy runs through Ranil’s career. The Central Bank bond scam, carried out under his premiership: his handpicked governor: another old boy of Colombo Royal College, disgraced, Ranil himself was untouchable. The Easter Sunday bombings: intelligence warnings ignored, nearly 300 dead, economy in freefall, no resignation.

Boris’s hypocrisy was louder, more theatrical. Downing Street’s ‘Partygate’; wine and laughter in COVID lockdown, while a nation grieved in isolation. A nurse in Yorkshire watched patients die alone, only to see photographs of the prime minister raising a glass. Ranil’s hypocrisies are quieter, more systemic, layered over decades of impunity. But the effect is the same: leaders who escape the consequences of the very crises they preside over.

Career without conviction

Neither man was guided by principle. Boris did not believe in Brexit until it offered him a ladder to the pinnacle of power. Then he became its champion, the clown turned bulldog, the opportunist turned prime minister.

Ranil has been liberal, nationalist, technocrat, depending on what the moment demanded. His single unchanging conviction has been his own presence in office.

That careerism came at a cost. Boris hollowed out the UK’s Conservative Party, filling it with mediocrities loyal only to him. Ranil hollowed out the United National Party, grooming incompetents, narrowing its base, until it collapsed into a single seat. Each man gutted his own party to preserve himself.

Narcissism and grandiosity

Boris imagined himself Churchill reborn; British bulldog with pint glass, the saviour of Brexit Britain. Ranil imagined himself as Sri Lanka’s Kissinger, the lonely realist, the adult among squabbling Rajapaksa clones.

But their people saw different images. In Britain, a son barred from his father’s funeral saw photographs of the prime minister’s illegal parties. In Sri Lanka, a student who had camped at Galle Face for weeks, was beaten as security forces cleared the site. “We want system change,” he told a journalist later, still bruised.

The narcissism was in believing these images would not endure, that the mirror would always be kinder than memory.

Hubris

In Ranil’s endless manoeuvres; his willingness to accept power without mandate, his comfort in presiding over collapse, so long as he remained untouched; one sees the rhythm of the country itself. Always on the edge of reform, always postponing the hard choice, always masking weakness with the theatre of rhetoric.

Ranil, like modern Sri Lanka, has survived everything: insurgencies, bankruptcies, burned libraries, broken parliaments. And like the state, Ranil has carried himself with a curious hubris, as if survival itself were an achievement, as if endurance without renewal were destiny.

Boris thought he would be remembered as the man who “got Brexit done”. Ranil thought he would be remembered as the man who “saved” Sri Lanka from economic disintegration and political anarchy.

But their legacies are smaller. Boris will be remembered for illegal parties in Downing Street while Britain mourned. Ranil will be remembered for shielding the Rajapaksas.

Hubris is the belief that power is destiny. What remains instead are images of betrayal.

The mirror again

And so the photograph returns. Ranil Wickremesinghe, enlarged on bail, flashing Boris Johnson’s Unleashed like a credential.

But it was not a credential. It was a confession. For in that book lies the same story: the old boy network, the narcissism of survival, the easy disposal of principle and people for self-preservation.

Boris once posed with Churchill’s bust. Ranil now poses with Boris’s memoir. Both men borrow gravitas, both men clutch props that betray them.

The mirror is merciless. Ranil wielded Unleashed as if it were armour. Instead, it revealed him; the careerist without conviction, the egotist with delusions of grandeur, the last man standing from his uncle J. R. Jayewardene’s 1977 cabinet, having outlived Ranasinghe Premadasa, Lalith Athulathmudali and Gamini Dissanayake.

Two islands. Two elites. Two schools. Eton and Royal. Downing Street and Temple Trees.

The same story, told twice. And the tragedy is not theirs. It belongs to their nations, the slow decay, the indignity of their hubris.

Ruben Thurairajah is a Yorkshire-based general practitioner in Britain’s National Health Service; who also tweets https://x.com/RubenThurairaj and writes https://drruben.substack.com/

Photo credit: Harin Fernando

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...