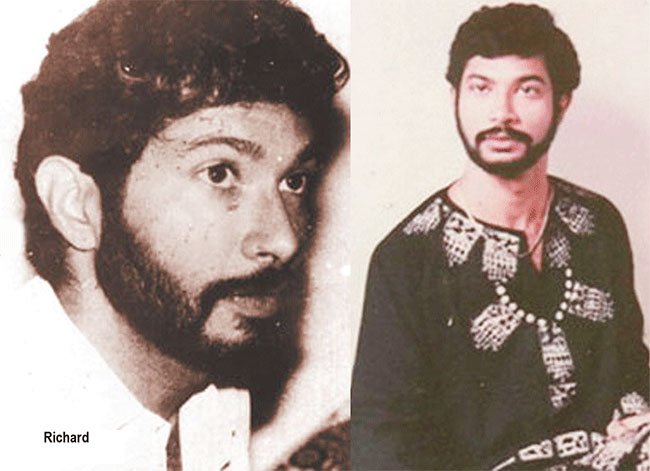

Richard de Zoysa: A Legacy of Injustice and Resistance

Manikya Kodithuwakku

This year marks the 35th death anniversary of journalist, human rights activist, and actor, Richard de Zoysa. As de Zoysa’s killers still remain at large with no one thus far convicted for his killing, the memorialising of his life and death symbolises the importance of contesting sanitised, selective narratives.

While much has been written and spoken about the political context of the killing, details of the initial magistrate’s inquiry into the death are less well known. Therefore, this article explores the primary witness/complainant’s legal counsel Batty Weerakoon’s discussion of the death inquiry proceedings of the Magistrate’s Court, in his 1991 booklet Xtra-Judicial Xecution of Richard de Zoysa, cited here with the relevant page numbers when referenced to minimise narrative disruption. This exposé reveals the ways in which investigative and legal processes were delayed, compromising the rule of law and making a mockery of due judicial processes.

It’s an interesting time in Sri Lanka to return to this dark chapter in its history. Both the presidential and general elections last year saw conservative political parties use political slogans such as ‘Mathaka de?’ and narratives of the ‘Bheeshana Samaya’ to evoke memories of the violence of Janatha Vimukthi Party (JVP) insurgents in the 1988-89 years. This electioneering strategy underscores a continuing attempt to control the narrative by remembering the violence of the 1988-89 period selectively, trading off in the process the then-government’s culpability and complicity. These efforts to unify historical narratives struck a discordant note with the memories of those who lived through the violence, which included allegations of silencing dissent and extrajudicial killings. In the lead up to the elections, sections of the public continuously countered and reinterpreted this narrative by invoking the violence of the state during this period, reflecting the memories of the people’s lived reality at the time, as well as those voiced through scholarly work, and witness and political narratives in the last few decades.

This counter discourse also played a crucial role in the public’s rejection of the sanitised narrative conservative political parties sought to memorialise through their rhetoric. In this counter discourse, the injustice of Richard de Zoysa’s abduction, torture, and killing over three decades ago has become emblematic in challenging the sanitised narratives of the violence of the 1988-89 period.

* * *

The 1988-89 period in our history is characterised by stories of the terror unleashed by the JVP during its second insurrection while the counter discourse is characterised by narratives of the then-government’s counter-insurgency actions. The insurgency period was deemed to be over with the killing of the JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera on 13 November 1989, and several JVP frontline members afterwards. Yet, in a classic execution-style operation a mere three months later, de Zoysa was abducted by a squad of men—of which at least one individual was in a police uniform—and later found tortured and killed. Why he paid this cruel price remains a mystery even as several hypotheses were deployed at the time, and continue to circulate today.

The abduction and killing of Richard de Zoysa are narrated by his mother’s defence counsel Batty Weerakoon as having begun in the early hours of 18 February 1990, at the home of de Zoysa’s then-colleague Noeline Honter, where five men arrived at 2.30 a.m. and demanded de Zoysa’s location from Honter’s husband, allegedly at gunpoint. Having shared the address, Honter informed Arjuna Ranawana, another colleague, who immediately informed SSP Henry Perera, who in turn informed the night duty officer at the Welikada Police Station. De Zoysa’s mother, Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, attested that at 3.30 a.m. the same night, five armed men entered her home when she unlocked her door under threat. She stated that they searched the house until her son was found, who was then forcibly taken to a vehicle outside, and driven off. She filed a complaint at the Welikada Police Station at 4 a.m., by which time no effort had still been made by the police to ensure de Zoysa’s safety despite Ranawana’s complaint at 2.30 a.m. Using her social position, Dr. Saravanamuttu then contacted high-ranking state officials who assured her that her son was alive (D’Almeida 2018). The next day, her son’s body was found in the sea in Moratuwa with two gunshot injuries and signs of torture.

Richard de Zoysa’s fate is well contextualised by news reports from about three months before he was killed. For example, while the Sunday Observer of 3 December (1989) reported on several pending arrests of “subversives”, the Daily News of 5 January (1990) reported that the progress of these investigations revealed “a list of 80 names”.

A popular belief in the immediate aftermath of the killing was that it was to silence the parody play Me Kauda? Monawada Karanne?[1] in which it was assumed de Zoysa had been involved. This belief was reinforced by the fact that the producer of the play, a state municipal councillor, Laxman Perera had vanished without a trace a few days before the play was to open.

Another widely believed assumption was that the killing was sanctioned by the state to prevent allegations of its human rights abuses (in quelling JVP insurgents) being reported abroad by de Zoysa in his new role as Bureau Chief of the Inter Press Service’s (IPS) Lisbon office. De Zoysa was to have left Sri Lanka on 22 March to assume duties at IPS.

State newspapers appeared to reinforce this assumption, positioning de Zoysa almost as an enemy of the state in their reports. For example, police investigations were reported to have revealed that he had been working with the JVP military wing, which was believed to have been “responsible for the fear psychosis” in the country during the preceding year, as reported in the Lankapuwath newspaper on 2 March 1990 (as quoted in Weerakoon 1991: 7). In these reports evoking public fear, de Zoysa shifts from a victim to a threat to the public. In fact, in the state’s reportage, it appears that de Zoysa’s killing had victimised the government in more ways than one. The Daily News of 23 February (1990), writing about the probe into the killing, quotes Minister of Defence Ranjan Wijeratne framing the government as the victim of “people (with) a vested interest” while Presidential Advisor Bradman Weerakoon worried that the timing of the killing could “affect the thinking of aid donors.”

Despite state newspapers allocating space for various conjectures about the killing, the articles omit any mention of the manner of de Zoysa’s death and forensic aspects of the injuries, thus diminishing the professional style of the killing and the gravity of the crime. Even state officials appear to have ignored the professional style of the abduction and killing, continuing to refer to it as an ‘alleged abduction and alleged murder’, leading Batty Weerakoon to ask whether they assumed de Zoysa “…threw himself into the sea and shot himself in the neck and head!”.

These responses by the state reveal attempts to frame the victim as a threat to the public and an insurgent operative, rather than a murdered citizen to whom the state owed protection. The state’s response to the killing was speculative at best and defensive at worst. Its reaction to the killing appears two-pronged—deflection and denial—with its aim being to impute blame to an external party, deflecting it from its own ranks.

The Daily News of 23 February (1990) also attempted to bolster the state’s credibility by discussing the efficiency of its investigative process and competency of its officials. Yet, a month later on 23 March, the OIC of the Criminal Detection Bureau of the Moratuwa Police reported to the Moratuwa Magistrate’s Court that, despite his investigations of the crime, “he had nothing to report to the Court” (11). In fact, not even the postmortem report had been filed in court by this time. Weerakoon asserts that this report in fact was collected over a month after the killing, and that too only after de Zoysa’s mother brought its absence in the court filings to the attention of the Magistrate’s Court, which then ordered its filing. Moreover, even though Dr. Saravanamuttu had given evidence the day after the killing to the acting magistrate of Moratuwa that she could identify two of the individuals who had abducted her son, investigators had not asked her for even a description of these men. But as the case progresses, we see that it is this capacity for identification that leaves investigators scrambling at the inquiry.

As Dr. Saravanamuttu and her representative Weerakoon sought justice for the victim, the onus was on the state to investigate the killing, and bring to book its perpetrators. How this responsibility was discharged can be gleaned from the perusal of Weerakoon’s submissions to court and his letters to state officials at the time, as well as Dr. Saravanamuttu’s affidavits as the complainant, and the Attorney General’s (AG) report to parliament in August 1990. The processes deployed to delay the inquiry, and the casting of suspicion on the primary witness/complainant Dr. Saravanamuttu appears to have been the state’s strategy even as she persistently pursued justice for her son.

While police investigators had stated in earlier court appearances that they had nothing to reveal on the killing, on 1 June 1990, Dr. Saravanamuttu tendered an affidavit to court affirming her identification of SSP Ronnie Gunasinghe as one of the individuals who had abducted her son. In response, Chief Investigator SSP Gamini Perera stated to court that he would arrest the suspect and requested an identification parade to be held when he was produced. Moreover, on 5 June, Dr. Saravanamuttu gave a statement to the same SSP of having received ‘credible information’ on the involvement of three police officers, Inspector Ranchagoda, Inspector Devasurendra, and Officer Sarathchandra. She had stated that, while she did “not recall” seeing the second officer at her home, her “recollections of the man…in police uniform on 18th February tallied with the description” of the first officer (22). It was while awaiting more information on these that she recognised SSP Ronnie Gunasinghe on the television news, and subsequently in a newspaper photograph.

Perhaps this was why at the next court date, 11 June, the SSP stated that he was not producing the suspect since “Dr. Saravanamuttu has stated in her statement… that she definitely identified the suspect…” and he therefore saw no need for an identification parade (12). The investigators’ failure to conduct an identity parade after the complainant’s identification is also highlighted in the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) observer Anthony Heaton-Armstrong’s report in August 1990.

On the same court date, investigators also reported finding a death threat issued to de Zoysa, which allegedly held him responsible for the death of film star Ramani Bartholomeusz although another individual had been convicted for the crime two years earlier. Weerakoon appears to hint at the absurdity of this ‘finding’ by questioning why it had not been reported in open court and only included in the investigators’ report (11).

Upon court’s questioning the police on their failure to produce the suspect as agreed previously, the investigators cited the necessity for further investigations before an arrest, resulting in the magistrate referring the police to the AG under S. 393[2] of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) for a decision. Given that the police had not had any findings to report even after the primary witness had confirmed her having identified one of the individuals, this referral to the AG would have been a welcome relief. But the proceedings at the next three court dates tell a very different story.

Complicating the investigators’ seeming slowness, Weerakoon moved the court to allow him to lead evidence under S. 138 of the CPC “to enable the Magistrate to decide as to whether there was sufficient reason to issue a warrant of arrest against a suspect not named in a report filed in Court” (12). The court allowed his application on the next court date, 5 July. However, this was not to be when the AG applied for more time to consider the case, and moved that he would lead the “necessary evidence” (13). But then, in a move that surprised Weerakoon, the state counsel asserted that “…such evidence would be that of witnesses whose statements had not been recorded by the police” (13, emphasis added). This meant that the testimony of the key witnesses to the abduction, Dr. Saravanamuttu, and her house staff and neighbours, would not be led as they had already been recorded by the police.

Weerakoon believes that had the state counsel said that he was advising the police not to produce the suspect, it would have allowed Dr. Saravanamuttu to give evidence. This would have resulted in the magistrate having to decide whether a warrant should be issued against the suspect. He supports this belief by arguing that had such evidence been given, it would have compromised the police case which he believed sought to maintain that neither she nor any other witness had mentioned an individual with a description that would fit the suspect’s appearance. Had Dr. Saravanamuttu’s evidence been led, it would have put into play one of the most basic tenets of judicial inquiry – that of a presiding judicial officer being able to test a witness’s evidence by questioning her to clarify any conflicts/omissions in previous statements in court. Weerakoon affirms this in a later letter to the President, dated 4 November 1990, that “no Court gives any weight to an alleged contradiction in evidentiary material unless such contradiction is put to the person to whom it is attributed, and such person is thereby given an opportunity to explain it” (35). Heaton-Armstrong (1990) too points this out in his report, asserting that Dr. Saravanamuttu’s credibility should have been a matter for the court. The state’s decision to lead evidence, but sidelining the testimonies of key witnesses, demonstrates an attempt to leverage legal processes and its formalities to delay or stall the judicial process.

Having stated that he would lead evidence, state counsel requested two weeks to make a decision, and the case was postponed to 16 July, which would be the penultimate day of the magistrate’s inquiry. It must be kept in mind here that the magistrate had referred the police to the AG for a decision on her order to produce the suspect identified by Dr. Saravanamuttu. However, on the penultimate day of the inquiry, it appears that the decision the AG had been considering was that of framing charges on the suspect.

In court on 16 July, state counsel stated he would lead evidence under S. 124, which is a directive to the magistrate to assist in ordering an identification parade. He gave no reasons as to why he was not leading evidence under S. 138 of the CPC, under which the court had granted leave to Weerakoon. He also stated that the police had submitted to him the statements of seven more witnesses, which had not been informed to court previously, as strongly noted by the magistrate. At this juncture, Weerakoon cited the extensive powers of the AG over Magistrate’s Court inquiries, and appealed for justice by calling on the AG to make a decision.

The AG would later report to Parliament, on 9 August, thus:

…the Magistrate…refused as unnecessary the request by AG to produce (Dr. Saravanamuttu and other witnesses). Expressing her refusal she (Magistrate) ordered that the AG may take whatever steps… (and report them to court) by 30th Aug (Hansard, 9 Aug 1990, emphasis added).

The next day, Weerakoon wrote to the AG about the issues of his interpretation of the magistrate’s order as a ‘refusal’. In response, in a letter dated 18 September 1990, the AG modified his position “restating it (as) ‘…the Magistrate was not inclined to allow my application’” (18). Regardless of these interpretations and reinterpretations, the fact of the matter was that the magistrate had given the AG a carte blanche in asking him to “take whatever steps” necessary, by his own admission. It’s safe to assume that the magistrate knew, as did the AG, that S. 398(2) of the CPC permitted the AG to instruct as he considers requisite on an inquiry and binds the magistrate to put into effect these instructions. Weerakoon concludes therefore that “…it is unthinkable that a Magistrate will disregard or overlook or refuse an application by the AG” (18). Yet, that’s how the AG interpreted the magistrate’s gift to him to seek justice.

Not surprisingly, on 30 August, state counsel informed court that the AG’s decision was to not take any steps to frame charges against the police officer identified by Dr. Saravanamuttu. Not surprising because, while Weerakoon alleged collusion between the police and the identified suspect, the magistrate herself questioned the AG in court on 11 June

…as to whether (SSP) Godfrey Gunasekera who appears with (the AG) is in this Court on behalf of the prosecution or to conduct the defence. I have seen him on several occasions secretively whispering certain things to Counsel for the suspect (36).

The reasons the AG gave to court for his decision were those that he had reported to Parliament a month earlier on 8 August. These reasons, cited as ‘weaknesses’ in Dr. Saravanamuttu’s affidavits, included “contradictions” between her affidavits and statements, the suspect appearing on the TV for only three seconds, the delay in filing the affidavit after identifying the suspect, and one of the officers submitted by her in her statement to SSP Gamini Perera on 30 June as having an official alibi. Weerakoon argues that while any contradictions could have been cleared up by the investigating officer who took Dr. Saravanamuttu’s statements, her identification of the suspect was from two separate news telecasts and a newspaper photograph. Moreover, the filing of affidavits was based on the given court dates and thus beyond her control.

At this juncture, even as counsel for the police officers requested a suspension of the magistrate’s inquiry, Weerakoon moved for a dismissal of the case. His far-thinking reasoning was that a suspended case would be sub judice to be discussed in public or in Parliament, which would essentially erase it from the public conscience as court postponements piled up. But when the killing did come up for discussion in Parliament a mere few months later, the state would nevertheless argue sub judice. In September 1990, Opposition Leader Sirima Bandaranaike moved the motion calling on the president to appoint a Commission of Inquiry into de Zoysa’s death. But in December, the motion was stopped in its tracks when Leader of the House Ranil Wickremesinghe objected to it, citing it was sub judice: the suspect Ronnie Gunasinghe identified by Dr. Saravanamuttu had begun civil proceedings against her on grounds of defamation![3]

Thus, the magistrate’s inquiry into the killing appears to have been frustrated by the investigating officers in the first instance and when referred to the AG, by the state counsel’s intervention both to prevent Dr. Saravanamuttu’s evidence being led (as ordered by the magistrate) and sideline the other key testimonies. These manoeuvres successfully prevented an opportunity for the magistrate’s independent scrutiny of the witness’ evidence. Taken cumulatively, such actions and tactics reveal some master moves at the highest echelons of power to silence the murder of a citizen, risking further erosion of public trust in the judicial process at the time.

The primary witness/complainant in the abduction, Dr. Saravanamuttu died in 2001 without seeing justice served for her son’s killing. Public reports indicate that three of the four police officers whose names had been submitted to SSP Gamini Perera by Dr. Saravanamuttu in June 1990 were subsequently charged with de Zoysa’s kidnapping and murder in 2005.[4] Later the same year, the officers were acquitted of all charges by the High Court, citing a lack of credible evidence. No one else has been convicted for the killing as yet. Thus, even 35 years after the killing, the state has been unable to achieve justice for de Zoysa by bringing to book the perpetrators.

Annually memorialising his life and killing, usually in February, positions his assassination as a legacy that contests the selectively evidenced, unified narrative of the state which seeks to erase/suppress narratives of the thousands of youths killed/disappeared during the 1988-89 period. Today, his killing continues to be a site of resistance to the violence of hegemonic political narratives and its erasures. The injustice of de Zoysa’s killing symbolises the counter narratives of this period and also serves as a powerful reminder to those accountable to the people that public memory lives on no matter what the history books say or attempt to erase.

Thus, the injustice of Richard de Zoysa’s killing remains emblematic of political expediency and impunity, and memorialising it endures as an act of resistance against attempts to expunge inconvenient truths that challenge selectively evidenced, sanitised historical narratives.

Manikya Kodithuwakku is a senior lecturer in the Department of Language Studies of the Open University of Sri Lanka. She is co-author of The Pen of Granite: A Richard de Zoysa 25th Year Memorial (2015).

Image source: https://bit.ly/4hS0sfu

Selected References

Asian Human Rights Commission. (2001). “Dying Without Redress: A Tribute to Manorani Saravanamuttu [Sri Lanka], A Mother Who Fought For Justice.” (19 February). Available at http://www.humanrights.asia/resources/books/monitoring-the-right-for-an-effective-remedy-for-human-rights-violations/dying-without-redress-a-tribute-to-manorani-saravanamuttu-sri-lanka-a-mother-who-fought-for-justice/#:~:text=Manorani%20will%20be%20remembered%20as,rule%20of%20law%20and%20morality

D’Almeida, Kanya. (2018). “Press Freedom & Enforced Disappearances: Two Sides of the Same Coin in Sri Lanka. Opinion.” Inter Press Service (30 April): http://www.ipsnews.net/2018/04/press-freedom-enforced-disappearances-two-sides-coin-sri-lanka/

Heaton-Armstrong, Anthony. (1990). Magisterial Inquiry into the Homicide of Richard de Zoysa. Geneva: International Commission of Jurists. Available at https://sangam.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Homicide-of-Richard-de-Zoysa-fact-finding-mission-report-of-Int-Commission-of-Jurists-Aug-1990.pdf

Perera, Vihanga. (2021). “Richard de Zoysa: The Poet in a Decade of Chaos.” Sri Lankan English Writers Review (1 August). Available at https://srilankanwriters.wordpress.com/2021/08/01/richard-de-zoysa-the-poet-in-a-decade-of-chaos/

Perera, Vihanga. (2024). “A Quest of Truth: The Inspiration of Tarzie Vittachi in the Political Poetry of Richard de Zoysa.” Vidyodaya Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 9(2): 112-123. https://doi.org/10.31357/fhss/vjhss.v09i02

Perera, Vihanga, Manikya Kodithuwakku, and Dhanuka Bandara. (2015). The Pen of Granite: A Richard de Zoysa 25th Year Memorial. Colombo: PawPrint Publishing.

Pinto-Jayawardena, Kishali. (2010). Still Seeking Justice in Sri Lanka. Bangkok: International Commission of Jurists.

Weerakoon, Batty. (1991). Xtra-judicial Xecution of Richard de Zoysa. Colombo: Self-published.

[1] ‘Me Kauda?’ was an election slogan of the then-president elect, Ranasinghe Premadasa, in 1988. At the time, it was believed that the play was financed by a group that had defected from the president’s party, the United National Party (UNP).

[2] S. 393(5)(e) of the CPC: “The Superintendent or Assistant Superintendent of Police in charge of any division shall report to the Attorney-General every offence committed within his area where …(e) the Magistrate so directs…”.

[3] However, on 18 December 1990, the speaker allowed the motion to be debated “…subject to references made to the suspect, who is the plaintiff in this case…” (Hansard 18 December 1990).

[4] The first suspect Dr. Saravanamuttu had identified, SSP Ronnie Gunasinghe, was never charged, and was killed in a bomb blast alongside President Premadasa on 1 May 1991.

You May Also Like…

Polity Vol. 12 No. 2

Compass on an Old Course? - Editorial Settler Tourism and the Threat of Terror - Praveen Tilakaratne and Tamara...

The development of S.B.D. de Silva’s political economy

Shiran Illanperuma

For those who knew him or have read his work, the late S.B.D. de Silva could be considered one of the greatest...

Aid Interrupted: Reverberations in Sri Lanka of USAID’s Dismantling

Sandunlekha Ekanayake

Trump’s ‘America First’ doctrineIn a shocking move, President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ right-wing populism and...