Reflections from a State Quarantine Centre during COVID19: Militarisation of the Welfare State in Sri Lanka

Thavarasa Anukuvi

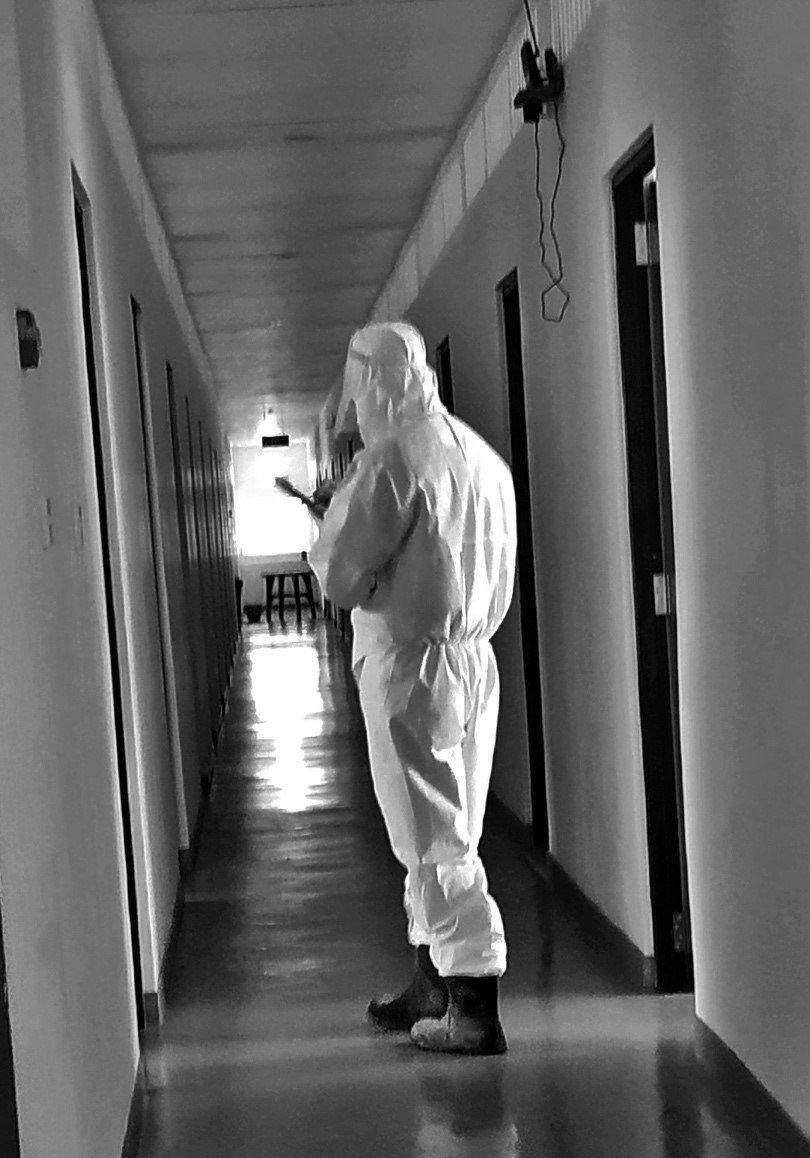

Sociologist C. Wright Mills (1959) defines sociological imagination as a vivid awareness of how personal experiences and personal challenges are shaped by social factors, including public matters. Mills argues that as individuals we are often unaware that the challenges we face bear the imprint of the wider society, or are even outside of our control. In the case of COVID-19 many have argued, including people outside of the social sciences, that the challenges we face in its wake are exacerbated by existing inequalities and structural discrimination. Therefore, many voices have emphasised the importance of state welfarism during the pandemic not just as a means of providing essential goods, but also efficiently facilitating healthcare and ensuring basic income support to people in need. Against this backdrop, I contend that Mills provides us a lens through which to see how public circumstances shape our personal lives, and the lives of others with reference to the pandemic, and to tap into our sociological imagination to become more aware of the connection between personal experiences and the wider society. This essay draws on my own experience at a government quarantine centre, and photos taken therein, to briefly reflect on militarisation of welfare provisioning in Sri Lanka. The narrative is located in the context of the early pandemic period, specifically June of 2020, when the country was preparing for the parliamentary elections of August 2020.

State Quarantine Centre Diary

Our flight to Colombo arrived at Bandaranaike International Airport at 730 am on 22nd June 2020 with 300 passengers on board. We were eight students from the South Asian University, New Delhi; while other passengers were businessmen, tourists, and other students from various universities in India. It was a thrilling three-hour journey from New Delhi, India. I had at this point been quarantined for three months at my residential university hostel, and was finally returning to my country.

When we reached the airport, all passengers had to undergo a temperature check and proceed to a place designated for arrivals where we, along with our luggage, were sanitised. All these procedures were implemented and monitored by the Air Force and army. Once the immigration formalities were complete, everyone underwent a PCR test at the airport. Following the test, we were divided and assigned to different state quarantine centres.

In the wake of the pandemic, the government set up quarantine centres as a mandatory requirement for those coming from abroad. There are two kinds of quarantine centres: government quarantine centres run under the direct supervision of the military for free, and paid quarantine centres, mostly re-purposed luxury hotels, also monitored by the military, that charge LKR 7500 upward per day. At the time, there were approximately 54 quarantine centres throughout the country which were run by the military.

Around 80 people, including myself, were taken by buses to a military-run free quarantine centre in Homagama, which was around an hour’s ride away from the airport. The centre was set up in a newly constructed university hostel. Our luggage was once again sanitised at the quarantine centre. Two of us were assigned to a room measuring about 16 x 20 feet in size. There were two single beds, two tables with a chair each, a cupboard, toothbrushes, toothpaste, soap, washing powder, shaving blades, shampoo, cups and saucers, and one pair of foot wear for each occupant. A five-litre drinking water canister, pillows, bed sheet covers, and internet connection were also provided. My friend and I decided to share a room, which was reasonably comfortable. Approximately 15 students shared a common bathroom; three people were from my university and the remaining students came from different universities throughout India.

We had nothing to do in quarantine. Many watched movies, some read books. Video calls became a crucial part of the experience. On our floor, there were several music students who played different kinds of instruments which we could hear in our rooms. I felt that one cannot ban music even in a military quarantine centre. The picture below shows one of these students as he practiced the Sarangi, which he did every morning and evening. He played it as he was sitting on his bed which was right in front of mine. I saw him every day as you see in this picture. Many others also played music and sang songs in their rooms; and though I could not see them I enjoyed listening to their music from my room.

Our first PCR test was negative and yet we had to take another test on our 10th day after arrival. We could not take relief from the result of our first test, but instead began to anxiously discuss our second PCR test. My roommate was not looking forward to the second test, as during the administration of the first he was hurt with a nosebleed. Therefore, he kept expressing his concerns about the next test.

The second PCR test was eventually conducted on our 12th day in quarantine. Doctors from the COVID-19 special medical unit came over and took samples. This time my friend and I were again negative. But the experience was worse for me than for him, as I experienced some pain the rest of the day. Many prayed for a negative result. Everyone wanted to fail this test! Who wants a positive result in this case? We got our result the following evening. The good news was that no one had tested positive. If a single person from our floor had tested positive, everyone would have had to undergo another 14 days of quarantine.

Once we knew that all were safe, we could freely move to others’ rooms. We had planned a musical night on the last day. A few students on our floor had negotiated with the military officer in charge and he had agreed, but no one was to move to other floors. Around 15 students – Tamils, Sinhalese, and Muslims from different Indian universities – gathered in the common space on our floor. We introduced ourselves, had fun talking, shared our experiences during the pandemic in India, and exchanged contacts. As students, we had a lot in common to talk about and share: Indian cinema, South Asian politics, and the upcoming Sri Lankan election. There was a Sinhala student learning Carnatic music and he sang many South Indian songs which quickly connected all of us. We sang South Indian playback singer Sid Sriram’s Tamil song, ‘Kannaana kannae Kannaana kannae’ and the Sinhala song, ‘Lassana Lassana Mage Adariye’. Even though we were from different religions and ethnicities, music connected all of us as human beings who love music.

On the final day, we had a certificate ceremony which was organised by the staff of the quarantine centre. It was an institutionalised programme that took place in every quarantine centre in Sri Lanka. The entire programme was conducted in Sinhala, leaving many Tamil speakers unable to follow the proceedings. Lieutenant-level military officials were invited as chief guests. In their talks they glorified the government and the work of the military during the pandemic. The certificate was signed by the Army Commander, Lieutenant General Shavendra Silva, and Dr. Anil Jayasinghe, then Director-General of Health Services.

Immediately after the ceremony, buses to different parts of the country were waiting to take us home. Finally after four months of quarantine, it was a big relief to be going home. My travel from the Western part of the country to the Eastern was one of the longest I have experienced. Seven of us travelled in the same bus to the East, setting off around 11 am, and I was the last person to get off the bus around 1130 pm. An army soldier accompanied us and he was instructed to hand over the people to their local police stations where the police registered our details and then took us to our homes. After returning home, we could not meet anyone as we had to undergo a further 14 days of home quarantine.

In the next sections, I explore the extent of militarisation of the state response to COVID-19 and what it means for Sri Lanka as a political community.

Militarisation of Welfare

The provisioning of free quarantine facilities by the government has to be located within the remnants of the welfare state in Sri Lanka. The post-Donoughmore Constitution of 1931 laid the foundation for Sri Lanka’s welfare state focusing on poverty reduction, healthcare, housing, and free education (Jayasuriya 2004: 11). Universal suffrage from 1931 onwards also contributed to strengthening the welfare state in Sri Lanka. For instance, the implementation of the Education Act of 1943, the establishment of the Department of Social Services in 1948, and the Health Act of 1953 sought to legally expand the state of welfarism in Sri Lanka (Wickramasinghe 2006: 319-321). However, the welfare state was progressively and substantially dismantled since the late 1970s, even though people still saw the state as the chief provider of services (ibid: 317-318), particularly due to their benefitting from, for example free education and free healthcare. Political parties and politicians also frequently mobilised their constituencies by drawing on welfarism and welfare schemes. My quarantine experience, however, signals the extent to which welfare provisioning is being militarised under the Presidency of Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

The first COVID-19 case was confirmed in Sri Lanka on January 27, 2020, after a 44-year old female tourist from Hubei Province in China was admitted to the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (Colombo Page 2020). When the first Sri Lankan national tested positive in Sri Lanka on March 10, 2020, the government formed a ‘National Operation Centre for Prevention of COVID-19 Outbreak’ (NOCPC19) as the national body for dealing with the pandemic. Lieutenant General Shavendra Silva, the Sri Lankan Army Commander, was appointed as the head of the centre (Daily FT 2020).

NOCPC19 is in charge of a wide range of activities seeking to tackle the pandemic, such as building treatment centres, imposing lockdowns, and maintaining quarantine centres. In addition, senior military officers have been appointed to all 25 districts to coordinate the COVID-19 response at the district level (Pothmulla 2020). In this context, how can we conceive through our sociological imagination the military’s involvement in health-related issues in the pandemic?

In order to understand these circumstances, I borrow the concept of ‘securitisation’ which was initially coined by Mark Duffield in relation to the development of new regulatory technologies of social control that occurred in public management in the late 1980s (Duffield 2002) and applied by Jonathan Spencer (2016) to the Sri Lankan context. Spencer (2016) uses the term to describe army enlargement in unexpected domains like tourism, urban planning, and university students’ training during the Presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa between 2009-2015.

Spencer also links the concept of securitisation with Neloufer de Mel’s work on militarisation where the latter is defined as “a step-by-step process by which a person or a thing gradually becomes controlled by the military or comes to depend for its well-being on militaristic ideas and military advancement over civilian institutions and visibly relies on the military and police to regulate civilian movements, political solutions or expand boundaries in the name of national security” (De Mel 2007: 12). This is not to reduce the problem of militarisation to individual service-personnel but rather to point to the larger project of securitisation of governance in Sri Lanka, and the government’s use of the COVID-19 pandemic as an occasion to militarise civil sectors including healthcare, and to create the sense of a country on a war-footing.

Several politicians, including the President, have claimed many times that the country is in a war-like situation, referring to the COVID-19 outbreak (Weerakoon 2020). As if to prove this, military personnel have been appointed to positions across the healthcare sector under the NOCPC19 headed by the Army Commander. This is not to belittle the public service of the military as designated essential workers during a global pandemic, but to point out that this is not war time. Healthcare falls within the purview of civilian affairs, and so must be administered by the civilian sector (Human Rights Watch 2020). The preference for military management of affairs in this situation may thus indicate a broader securitisation project.

Humanitarian work carried out by the military was especially highlighted during the pandemic when Sri Lankan students were stranded in China’s Wuhan Province at the early stages of COVID-19. The government sent a flight to bring them back, and broadly stamped this as a ‘mercy mission’ while the airline crews were celebrated as national heroes (News1st Sri Lanka 2020). Such phrases as ‘mercy mission’, ‘humanitarian operation,’ and ‘the army in the frontlines of the battle against COVID-19’ are expressions that have frequently appeared in the media to normalise the work of the military in civilian sectors and to give a sense of a country at permanent war. This ethos was very much present in the operational protocols of the quarantine centre as well, whereby people were identified by numbers. Our food parcels, water canisters, tables, and chairs were all numbered, sapping us of the nuanced identity of personhood. This militarised use of numbers was also an exercise of power on the individual person.

The certificate ceremony which took place on the final day in the quarantine centre was itself a promotion of the securitisation project. It bore testimony to the importance of spectacle in an increasingly securitising state; spectacle that, with its great fanfare, glorifies (and, in the process, justifies) the service of the military during this time of great peril.

However, as COVID-19 infections began to escalate at an alarming rate as of May 2021, there has been increasing criticism directed at the military and its handling of the pandemic in Sri Lanka. There have been forceful calls for more autonomy to be given to the healthcare sector to direct policy in the fight against the pandemic. Does this mean that Mill’s sociological imagination has come more alive? Can we say that we are, as a political community, becoming more aware of the social nature of our existence, how it conditions our individual experience, the relationship between politics and everyday life, and why it is important to be aware and active as members of a political community?

Thavarasa Anukuvi is an independent researcher and photographer.

References

Colombo Page. (2021). “Sri Lanka . First Patient with Coronavirus Reported in Sri Lanka”. Accessed on 27.05.2021. Available at http://www.colombopage.com/archive_20A/Jan27_1580144354CH.php

Daily FT. (2020). “Govt. Launches National Ops. Centre to Counter COVID-19”. Accessed on 18.03.2020. Available at https://www.ft.lk/News/Govt-launches-National-Ops-Centre-to-counter-COVID-19/56-697707

de Mel, Neloufer. (2007). Militarizing Sri Lanka: Popular Culture, Memory and Narrative in the Armed Conflict. New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Duffield, Mark. (2002). “Reprising Durable Disorder: Network War and the Securitisation of Aid”. In Björn Hettne and Bertil Odén (Eds.). Global Governance in the 21st Century: Alternative Perspectives on World Order (74-106). Stockholm: Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Human Rights Watch. (2020). “Sri Lanka: Security Agencies Shutting Down Civic Space”. Accessed on 03.03.2020. Available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/03/sri-lanka-security-agencies-shutting-down-civic-space

Jayasuriya, Laksiri. (2004). “Colonial Lineages of the Sri Lankan Welfare State”. In Kelegama, Saman (Ed.). Economic Policy in Sri Lanka: Issues and Debates (403-425). New Delhi: Sage.

Mills, C. Wright. (1959). The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pothmulla, Lahiru. (2020). “Senior Army Officers for 25 Districts to Coordinate COVID-19 Control Work”. The Morning (31 December). Accessed on 27.06.2021. Available at http://www.themorning.lk/senior-army-officers-for-25-districts-to-coordinate-covid-19-control-work/

Spencer, Jonathan. (2016). “Securitization and Its Discontents: The End of Sri Lanka’s Long Post-War?” Contemporary South Asia, 24(1): 94–108.

Wickramasinghe, Nira. (2006). “Sri Lanka: The Welfare State and Beyond”. In Sri Lanka in the Modern Age: A History of Contested Identities (1st ed). Colombo: Vijitha Yapa.

Weerakoon, Gagani. (2020). “11 Years Later: Back on the Frontlines, Fighting for You”. Ceylon Today (23 May). Accessed on 03.07.2021. Available at https://ceylontoday.lk/news/11-years-later-back-on-the-frontlines-fighting-for-you

Acknowledgements: This essay benefited from discussion with Eva Ambos. The author would like to thank her for suggesting reading material, points of argument, and analysis. He also thanks the editors for helpful and constructive comments on the article.