‘When the Devil Drums, We Dance’: Sex Work and Sexual Violence in Wartime Sri Lanka

Radhika Hettiarachchi

In the context of Sri Lanka’s civil war, transactional sex work was a particularly dangerous survival strategy for some women[1]; not least because they bear the scars of society’s ‘moral’ chastisement. Stigma is entrenched in the way sex work and sex workers’ means of subsistence—the use of their own bodies—is characterised socially, economically, culturally, and politically. It is filtered through a lens of patriarchal values that exert control over women’s bodies, and subject to colonial laws meant to protect Victorian chastity. All this makes transactional sex work difficult and insecure work for women, which is further exacerbated in wartime.

This article is a descriptive overview of sex work during the Sri Lankan civil war and aftermath, as it intersects with conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). Based on oral histories from the ‘Women’s Histories of Sex Work’[2] archive, it will explore the extreme violence experienced by sex workers and the challenges that they face in accessing justice, which often extends such violence, and its impact beyond the temporality and geographies of war.

Profile of Sex Workers

As a direct result of the Sri Lankan civil war, many women were forced to bear the sole economic burden of their women-headed households. Some of them chose—sometimes forced by circumstance—to take up transactional sex work. According to the Status of Sex Workers report (2023), peer-reviewed and produced by the Sex Workers and Allies South Asia (SWASA) network, the average sex worker is a woman between the ages of 26-50 years old. Many of the women whose oral histories are part of the Women’s Histories of Sex Work archive[3], are between the ages of 40-65 (in 2021-23) and nearly all are mothers. They come from low-income backgrounds such as the urban poor, daily-wage labourers, directly war-affected or rural farming communities, and are therefore generally poor and (conventionally) less educated. Some are married or in long-term relationships akin to marriage. Many are widowed or have been abandoned by their men, and function as breadwinners, on average, supporting two to five dependents comprising their children, partners, or extended families. In what is generally considered informal sector employment, they are either street-based, home-based, or spa/brothel-based, or a combination of the three in a few cases.[4] With mobile phones becoming more commonplace in the 2000s, sex workers themselves or sex-brokers or go-betweens (who were usually women) began scheduling return-customers over the phone to ensure their anonymity and to protect themselves from societal ridicule. Sex work during conflict, was not limited to those in directly war-affected areas, or in brothels in militarised, conflict-adjacent areas only, but spread throughout the country, where the impact of securitisation and wartime-fear-psychosis was ever present.

Many layers of vulnerabilities affect the lives of women who undertake sex work, including ethnicity, gender, religion and socio-cultural norms. These existing vulnerabilities that affect the safety and security of sex workers were further complicated within a kind of ‘ethno-geography of war’[5], where heightened securitisation prevailed. Sexual and physical violence from clients within a militarised society became part of the experience of sex workers, often without witness. The rights of the female body and how society views and ascribes sets of value-based conditionalities on what it means to be a woman (de Alwis 2022: 129,139)—embodying society’s own preoccupations with purity, morality, and sanctity within the society-determined roles as mother, widow, and wife that they are expected to replicate and reproduce—therefore make sex workers even more marginalised in the context of their safety, security, and access to justice (Miller and Carbone-Lopez 2013).

The legal context

Complicating the conflict landscape further, is the perception that sex work is illegal. The ambiguity of the laws that are applied to sex workers combined with social stigma can leave women vulnerable to systemic violence. The colonial-era Vagrants Ordinance, section 3(1)(b) penalises “every common prostitute wandering in public… and wandering in a riotous and indecent manner”, while section 7(1)(a) criminalises soliciting and “illicit sexual intercourse in public places”. Section 9(1)(a) of the Ordinance incriminates “any person who knowingly lives wholly or in part on the earnings of prostitution”.[6]

Subsequently, the Sri Lankan Supreme Court ruling in Saibo v. Chellam (1923: 25) held that, “Prostitution is not an offense per se under our law… as both according to the intention of the Ordinance and the words of the sub-section itself the latter has no application to sex workers who live on their own earnings” (cited in International Commission of Jurists 2021: 14). In essence, this would mean that a woman engaging in sex work should not be arrested for simply ‘being’ a sex worker, without the condition of being riotous, indecent, or soliciting (‘Panel discussion’ 2023).

According to the Brothels Ordinance, the sex workers based at a brothel cannot be arrested or charged[7] as the law only applies to those who keep, manage, act, or assist in managing the brothel, knowingly lease or own the premises for “habitual prostitution”.

However, in practice, sex workers are often arrested due to the long-held perception (including by law enforcement officers) that sex work is illegal which in effect presupposes guilt[8] and institutes a fear of the police. In some cases, when arrested, women are subject to sexual harassment, coercion, and bribery in the form of sex acts, which they are forced to choose because they are threatened with false drug charges which may carry a three-month prison sentence (Deshapriya and Arasu 2023). This, combined with other drug related offences for which they are arrested—or in the case of transgender sex workers “impersonation” as a charge—means that women sex workers who have endured conflict-related sexual violence are left fearful and mistrustful of law enforcement authority and unable to access justice, adequate recompense or support services.

Methodology

This research is grounded in a phenomenological approach. By documenting lived experiences during the war, the 35 narratives speak to the many forms of violent legacies of conflict. This emic perspective, with its focus on memory and the lived experiences of gendered and minoritised subjectivities, shape their meaning-making processes. Doing so foregrounds how women rationalise how and when they negotiate ‘acceptable’ or ‘manageable’ levels of violence, rather than engaging with and acting on the underlying structural violence. The women were approached through their peers and peer networks, and documented voluntarily in safe locations close to where they worked during 2021-23. While sex work is chosen by men and women in many socio-economic strata (acknowledging also that some are trafficked and exploited), this research focuses on the poorer socio-economic categories of women who are street-based or brothel-based that may be the most vulnerable to unwitnessed acts of conflict-related sexual violence (by clients or other perpetrators).

Aside from a few that wanted to be ‘seen’, many of them chose to be anonymous, which the arts-based tools used—such as trees of life, letter-writing, body-maps—that helped structure their narratives, made possible.[9] These story-telling tools were followed up with audio-visual interviews edited to foreground conflict-related sexual violence. The women storytellers (and their peers) were part of a series of residential workshops that focused on health, wellbeing, legal awareness, networking, and association building (three prior to and one after the documentation). The final workshop, bringing together many sex workers from across Sri Lanka with the intent of enabling connections and sisterhood, also gave them an opportunity to review their video narratives and validate the findings. This was prior to the travelling exhibitions that focused on public engagement and advocacy for sex workers’ rights and challenges to accessing justice for wartime and routine sexual violations.

Part I: Becoming a sex worker

One of the primary reasons for women to choose sex work during the war was because, for many, it was the only survival choice available to them. Generally, they were trying to cope with financial responsibility for their families, after the loss of a male family member to death or disappearance, or abandonment by their husbands or partners.

Meena[10] is a Malay woman from Vavuniya, who has been a sex worker since being displaced and widowed during the war when her husband ‘disappeared’. Destitute, she found her way to Kandy over time, where the family would stay at temples or at a bus shelter, along the way, eating food offered as almsgiving. Even the young children worked odd jobs in exchange for food and shelter, often vulnerable to physical violence and abuse. Along her journey from Vavuniya to Kandy, she took on and continued sex work for survival.

I wasn’t used to it. I also thought it was just embarrassing to me. Then I thought, how can we eat if I don’t go like this and find some money? If it’s clothing, I can even wash it and wear it. But one can’t just wait when at such a young age, my children came to me saying they were hungry. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023a)

The bitter experiences of living with the uncertainty of displacement and the utter, devastating loss of being forced to begin a new life away from all that is familiar, creates a sense of helplessness. But for most women this is not a feeling they can indulge, as their children depend on them. While fear of societal recriminations and the coalescing of their destituteness with moral degradation is always present (de Alwis 2022: 184), the discreetness of the spaces where sex work happens, offers some comfort which outweighs such fear of reprisal.

For Fathima, a Muslim woman in her late 50s born in Hatton, sex work was something she deliberated on and chose as a viable model of income that she could control to an extent. Her story of strength and survival spans violence and sexual coercion in the tea estates, war in the north where she lived after her marriage to a Tamil man, the LTTE’s sudden expulsion of Muslims from Jaffna in 1990, and life as an internally displaced person with a disabled husband in Puttalam.

At the IDP camp in Puttalam there were men who had lost their wives… so to fulfil their sexual needs, they came to women like us. It wasn’t sudden, they became friends first, then teased us, used filthy language, and would say things like “since your husband cannot do it, I’ll come help you out”. I thought about it, and as there was no other way to raise four children, I said yes. For Muslims this work is haram, the mosque will ostracise us and not give my children access to [Islamic] loans, so I do this in secret. I try not to go with Muslim men [within the camps], but with Sinhalese [in the host communities outside]. I don’t go with police or army men because when they are in uniform, I can’t tell if they are Sinhala or Muslim. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023b)

During the war, as in other times of economic crises, many women also sought employment in the Middle East, seeking a way out of poverty and war. For those in lower-income groups with limited or no formal education, with their only and greatest asset being a healthy and able body, sex work became one of the few available options after the money they had sent back ran out. For Abhi, a Tamil mother of three from Ampara, war, displacement, and being an unwed mother whose partner was killed, led her to seek employment abroad. She says, “even after going abroad, I had a lot of difficulties due to the man of the house”, with abuse that caused a pregnancy which she had to terminate with the help of a friend. After returning, a lover cheated her out of the money she earned working abroad. To provide for herself and her family, she has relied on sex work for over 20 years without the knowledge of her family.

Now I have no other way [to survive]. If someone comes [for sex] I say they are a relative. People around my house have complained to the police, saying there are people coming and going a lot… People speak, but I don’t take it to heart. Nobody is going to give me food. I have to find my own way. It’s not to build a palace, it’s to earn and eat. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023c)

Abhi’s narrative like the histories of many others, shows that sex work offers a lucrative living for many women that other forms of informal sector employment do not; particularly when sex work can be done in the evening hours, leaving time for sex workers who are mothers to be present for their children. Engaging in transactional sex work is a complex and delicate negotiation for women, particularly for mothers living within the confines of their ‘community’. Therefore, sex work often involved travel, whether it is simply to the next town, or within or across conflict zones. Towards the latter part of the war however, mobile phones made transactional sex away from home easier. And yet, the insecurity and unpredictability of travel, especially during wartime, often ended up making them vulnerable to sexual violence, harassment, society’s condemnation, and feelings of hopelessness.

Kamala, is a Sinhala mother of two in her late 40s from a border-village in Polonnaruwa in close proximity to the former conflict zone. As a widow with children to support, her experiences of war, harassment, and sexual bribery, speak to the experiences of many women who go outside their village to work. At the cost of her own safety, she says “if I get a call from a trusted customer, I go secretly without the villagers knowing and I have never got caught so far” (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023d). Her practice of working with customers outside of her village and with mutual agreement to protect each other’s secret is to avoid judgement, slander, and physical abuse if they are “found out” because she believes that society finds sex workers revolting, even if she herself doesn’t “think it is disgusting [work]”.

Many women were first introduced to sex work by a female friend or relative who themselves were sex workers. Whether street-based, phone-based, or brothel-based, there was a sense of safety and care in such sisterhood that may have provided women sex workers some relief and emotional support, as Inosha’s story reveals. She is a Sinhala mother of two from Kandy, once married to a Tamil man, living for many years in the north with her sister who also married a Tamil from the north. She experienced the horrors of war when she lost both her husband and sister (including her family), barely making it out to a camp with nothing but her children and what she was wearing. At the camp, she recalls that an older woman in a similar situation “was the one who first introduced me to this profession. We also needed money—there was no way to survive” (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023e). She speaks of the practical need to continue travelling for sex work, aware that their clientele preferred ‘fresh faces’ or that their safety—including from prosecution—required mobility.

When we are in one place for months on end, those policemen take good note of us. Then if they see us anywhere, they will chase us… [a woman police officer] comes in civilian clothing in a three-wheeler and overtakes us and catches us even before we go to the guest house with the customer. We have such problems on the road. That’s why we don’t stay in one province for a long time. Sometimes, if it is very difficult, we change places every month. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023e)

During the war, sex work for survival was a ‘choice’ for some women but was forced upon others. For children who grew up during the war, many forms of violence on the body and mind were commonplace, including the loss of family, broken trust, and growing up in displacement camps. Many of the women indicate that there is a loose correlation between the worst of such violence—sexual violence experienced in childhood—and their progression to sex work. For them, it was a gradual recognition that their survival could be bartered for sex—first in exchange for food for their families or basic needs while in displacement camps and later, in rebuilding their lives and socio-economic wellbeing.

Pushpa is a Tamil mother of one child. She believes that the immeasurable loss of innocence in sacrificing her sense of personhood to protect her family from harassment and the threat of death at such a young age, threw her and others like her head-on into a cycle of violence that is difficult to overcome. Rape can carry long-term stigma for the victim of violence, not only by the heinous act itself but by a loss of honour, respectability, and recognition of a family’s place in their society (Centre for Equality and Justice 2018). While the impact on the family, if placed on a hierarchy might seem less important than the victim’s own experience and pain, it might result in the ostracism of the family from society, impact the marriageability of siblings, and certainly taint the perceived ‘purity’ of the victim as a woman.

During the war we went and stayed in a camp. It is in that camp that the army raped me. Four of them took me… and raped me. Those six months it happened again and again. I got used to it like that. What to do… [I did it] to eat and drink… Because of that also, I lost my sense of shame. [I] thought about it, I couldn’t do anything else, my younger sister was small. What to do, the army was unjust and raped me so like that, I went into this job. I had no choice. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023f)

Women and young girls were also trafficked by the men they trusted—fathers, uncles, brothers, husbands—during the war. While the motivations were financial for some men, for others, it was leverage or wartime displays of allegiance to various powerful parties or militant groups that led to trafficking. In some cases, trafficking or trading children into sexual slavery lay at the nexus of cultural practices of child marriage, predatory sexual exploitation, poverty, and a lack of choices available for their families’ survival. In a sense, because this type of servitude for the benefit of their families marked their childhoods, the impact of such complex layers of pain on the fragile and helpless psyche of a child, may result in lifelong feelings of being unloved and untethered. As some women cite, this has resulted in drug-use and cycles of inescapable violence and marginalisation in adulthood.

Nasreen, is a Muslim mother of three in her early 40s from Mannar. Having been ‘sold’ into marriage as a child and into sex work by her much older husband, she speaks of her own courage and resilience in the face of suffering and unimaginable abuse to protect her own daughters.

I was ten. My mother gave me to him, but not in legal marriage. He sold me to the police and to the army. I was so young. I would cry and tell him I didn’t want this job. Then he would beat me. He sold me for 2,3,4, 5000 rupees…when I was small a policeman took me from behind. I was so small I didn’t know what was happening. I couldn’t sit after, but five minutes later he did it again even with blood pouring down my legs… At ten I didn’t understand that I was pregnant… I had to go back to this ‘business’ after my child was one and a half months old. At first, I was afraid but as time passed, I got used to it… (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023g)

While motherhood and caregiving are central to sex workers’ survival choices and identities—not only in why they enter but also why they choose to remain in sex work—how society prescribes that those roles be played complicates sex workers’ safety and security. Social structures—health care, social services, legal systems, and community policing mechanisms—do not provide alternatives or adequate safety networks for women sex workers, leaving them abandoned and vulnerable to structural violence in more ways than one.

Yet, despite these difficult circumstances of entry into sex work or the discrimination and threats of sexual violence that they may encounter ‘on the job’, the work itself provides a sense of independence that is considered by some women to be more important. While war is not conventionally thought of as liberating, it may have offered some women the opportunity to break out of their strictly defined social roles. Whatever the reason for entering and remaining in transactional sex work, this was a way for women to exercise their agency and take control of their own lives with courage and determination when the choices before them were bleak.

Part II: In the shadow of conflict-related sexual violence

For sex workers who worked in and around conflict zones, sexual violence ‘on the job’ was just another layer of abuse that they needed to endure by sheer courage rather than through existing mechanisms for justice. Thus, negotiating what types of violence was acceptable and what was manageable was sadly commonplace. For many the recognition that the violence and abuse that they had endured was beyond the consensual and agreed terms of transactional sex, especially in a conflict situation, became apparent only as they delved into their memories.

In many wars throughout history, the use of sexual violence is often strategic—to humiliate, torture and to weaken the ‘other’. The United Nations classifies conflict-related sexual violence as “rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, forced marriage and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls or boys[11] that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict” (Guterres 2019: 3). However, the case of deliberate sexual violence against women who have ‘chosen’ sex work for survival—the pros and cons of which they have carefully considered—as opposed to being forced or trafficked, is unique. It extends the definitions of conflict-related sexual violence to situations where there is a transactional contract or consensual agreement between two parties. Yet, it is also true that in situations of conflict these contracts occur within contexts that are characterised by distorted, unequal and extremely one-sided power relations.

As a result, the vulnerabilities of sex workers from minority communities were heightened during the war, particularly as they had a greater percentage of their clientele from the army and police rather than civilians. Vishwa, is a Tamil mother of two in her 40s from Jaffna. She was the wife of an LTTE ex-combatant who had endured war, her husband’s physical abuse as his own war-affected mental state deteriorated, widowhood and displacement. Having been introduced to sex work by another woman while displaced in Vavuniya, she says that she has “gone with police and army men” (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023h). Throughout, however, she feared them because “they are very rough. It’s scary to be with them. They don’t treat us gently. Because they are away from their wives, they are sexually deprived. So, they are abusive. They torture us.”

For sex workers who worked during and in the aftermath of the war, their experiences of sexual violence was not confined to those in uniform but also civilians. Violence therefore impacted sex workers disproportionately, because sex work always happened in the shadows. This was particularly the case, because sex workers travelled extensively, a ‘travel corridor’ tacitly agreed upon possibly because of the need to protect the heteronormativity of military men (Tambiah 2005). Travel meant traversing socio-cultural barriers such as social norms, perceptions of morality and even ethnic and language groups, as well as through securitised physical barriers such as checkpoints and in and out of warzones, making them doubly exposed and unprotected.

Luxmi is a Tamil mother of four in her 60s from Kilinochchi, who, after displacement was introduced to sex work by a woman in similar circumstances and travelled between Colombo and the north for sex work throughout the war to support her displaced family. Her experiences of travel in an era of heavy militarisation, as a sex worker and a member of a numerical minority, illustrates the realities of war and travel during the war compounded by the fear of being recognised as a sex worker.

When we travelled from Colombo to Jaffna or Kilinochchi, there were at least six main checkpoints that we needed to go through. They [army at checkpoints] ask us where we are coming from and what we do. We never tell them we are sex workers. If we tell them, they start to harass us… [at] each checkpoint they ask the same questions, and when they search us, they touch our bodies unnecessarily. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023i)

This was the case not just when sex workers were from ethnic minority communities but even as Sinhala Buddhists, whose inherent identity-privilege mattered less considering their vulnerability as women sex workers. It might be that society viewed them as ‘usable and abusable’, simply because they worked in a clandestine space and in a profession that was deemed ‘criminal’.

Kumari, is a Sinhala mother of three in her late 50s who worked extensively in Anuradhapura and travelled across battle zones regularly to Jaffna during her three decades as a sex worker. In brothels, and around areas frequented by military personnel, she recounts the extreme impunity with which women experienced sexual violence during the conflict.

They opened the door, grabbed me, gagged me and squeezed my throat. They took me… I could see that it was a beachy area…it was large land or jungle and a house with lots of rooms. I could hear people screaming, beatings… after that they kept me there for a week. Each day two to three people used me…they didn’t hurt me beyond that. [When I was kidnapped] I only washed myself once, they didn’t care about cleanliness or HIV or condoms. I could hear another woman in the other room shouting and scolding… They used us for their needs and let us go after a week so I did not bother going to the police. Because when a sex worker goes to the police, they tell us “They took you because you are a prostitute”. So, when something like this happens, we bear it. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023j)

During the war, even far away from the directly conflict-affected or conflict-adjacent areas, the dangers and vulnerabilities of sex work persisted. Sex workers were prone to surveillance, abuse and violence when civilian movement after dark was insecure and curtailed by strict restrictions, including arbitrary yet pervasive security measures such as ‘prevention of terrorism’. Swarna, is a mixed-race mother of two in her 50s from one of Colombo’s poorest neighbourhoods. Even away from the primary conflict-affected areas, she has experienced violence and abuse as a direct impact of the war, forcing her to prioritise her personal safety and security by choosing silence over justice.

Once a man came to me, and he said “come with me” and held a pistol to my back… he took me to a room in Colombo… he asked me some questions… he said don’t lie, terrorists give you papers or messages to pass on at night, don’t they?” …They got rougher and said they would beat me. I said “even if you kill me this is all I have to say”. They [presumably CID] said that it was people like us [sex workers] that the LTTE selected to carry messages or keep bombs in places because we do anything for a bit of extra money. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023k)

Because of the stigma with which sex workers are perceived, the unchecked harassment and sexual bribery that they have experienced at checkpoints, was never reported. For those who were non-binary or transgender women, such harassment was routine. The weight of society’s perceptions of morality and gender norms played out more insidiously and dangerously when exercised by their own ethno-religious communities, who themselves were under strain from heavy militarisation or a tense wartime atmosphere.

Mithuri, a Sinhalese transgender woman from Colombo, has worked throughout the war. In her experiences, she recognises her unconventionality as a factor of her exploitation,

[If] I must go from where I am to Negombo [for sex work] and there are barracks here and there… I will [have to] go through a checkpoint. When we go, they ask us where we are going, and we say that we are going to earn some money. When we explain the details to the person, they have sex with around three to four of us and let us go… We would have sex inside their barracks. There would be barrels everywhere so we weren’t visible at night. So, we would have to contort our bodies [behind barrels] and have sex with them… yes, it is a sexual bribe… These officers, instead of doing their duties, always look for ways to take advantage of someone else… What are we supposed to do? The officers would drum on the barrels and tell us to dance and sing a song and we would perform funny acts. What we wanted was to somehow be able to pass the checkpoints… so when the devil drums we dance… We would also feel a certain measure of hate. After all, they are having sex with us and not even paying us anything… we live with death holding our hand. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023l)

Thamarani is a transwoman LTTE ex-combatant who joined the militant movement as a teen, because she could no longer bear the societal discrimination she faced or her own family’s treatment of her as ‘deviant’. She saw herself as female from the age of 10, which she believes caused her own mother to wish aloud that “she [Thamarani] had died”. After she left her battledress behind during the last battle of 2009 in Puthukudiyiruppu, she took up sex work as a transwoman. However, she was continuously threatened by those who wished to expose her as an ex-combatant, for their own gain, long after the war ended. The legacies of conflict and violence therefore continued to impact her ‘everyday’ safety.

They asked me, “were you in the Group?” I said “no”. It happened in Kilinochchi once… they said “come here prostitute and lie down”. They closed my mouth and dragged me away. They said “you can be a man, why are you wearing these clothes”, and I said “we dress like [women] because our inner feeling is this [a woman]”. When I said I am going to tell the police, they say “what is the police going to do?” … so, we live in fear of this [violence]. They [then] hit me with a bicycle and strangled me. I thought it was over and I was relieved and when everything was over, they poured super glue on my genitals… I wished I had died [when I was with] the militant group [her time on the frontlines of battle]. (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023m)

The impunity with which those on the higher end of the power-spectrum were habitually violent towards sex workers is not simply characterised by their ethnicity or the limits of conflict-affected areas. During the war many women sex workers, who come from diverse ethnicities experienced sexual and gender-based violence regardless of where they worked or who they were. The common denominator they shared was that they were at the margins of societally ascribed ‘morality’, the lower end of the economic spectrum, and had no recourse to protection of the law.

Part III: Conflict-related sexual violence, justice and peace of mind

The complexities and violent legacies of conflict extend beyond that historical moment to the present day for women who are still engaged in the commercial sex industry. It impacts their agency and ability to engage in this livelihood with peace of mind, if they are not free nor able to access justice for violent crimes committed against them. When presenting to the Human Rights Council in 2024, the UN special rapporteur on violence against women and girls framed all sex work as inherent violence against women and girls (Alsalem 2024).

The unfortunate usage of the term ‘prostitution’ and its stigmatising historical connotations, as well as the significant conflation of trafficking with ‘prostitution’ in the report are also problematic. It is possible that the impetus for choosing sex work for survival, or some level of agency that women exercise in choosing it as a lucrative profession can be linked to systemic and entrenched issues of marginalisation, gender norms, and patriarchal values.

However, characterising all sex work as inherently violent is essentialist, and robs women who choose to engage in sex work of the important need to signal sex work as labour in order to address sexual and gender-based violence that lies outside the terms of transactional sex (SWASA 2024). When the social and structural system within which it exists sees no dignity, let alone a framework that allows safety for such types of labour, it can be a humiliating and demoralising process to voice their justice claims for sexual and gender-based violence, especially during conflict.

For sex workers who have worked during and as a result of the Sri Lankan war, there are many reasons why justice for conflict-related sexual violence remains elusive. First, sex work always happens in the shadows. During the war, it was particularly invisible as it happened after-hours, during curfew, geographically and physically away from the public eye, whether inside the conflict-zone or in conflict-adjacent areas where even journalists had scant access. Therefore, the sexual and societal violence that are routinely experienced by sex workers remain unwitnessed.

Second, sex workers lack faith in the justice system. Coupled with the pervasive culture of a lack of accountability for and acknowledgement of other wartime atrocities—such as enforced disappearances—making complaints about sexual violence to the ‘authorities’ is futile for sex workers. When cultural norms such as purity and morality are commonly equated with ascribed ‘women’s roles’ of mother, wife, and caregiver, the preservation of such narratives becomes an imperative within post-war nation-building processes (de Alwis 2022). The stigmatisation and prejudice sex workers face when society considers them deviant or degenerate translates to the near impossibility of redress for sexual violence against them in conflict-contexts, and the way sex workers experience the (often mishandled) application of the law in Sri Lanka.

Third, sex workers themselves place accountability lower in their hierarchy of needs. To them protecting and providing for their children and families, negotiating and managing their ‘respectability’ in society, their health and medical needs, financial security especially in old age, and their physical safety within their work environments supersedes the need for reparations for conflict-related sexual violence. As such, sex workers often consider harassment and violence to be ‘part of the job’—a normalisation of structural violence which might echo the UN special rapporteur’s framing of sex work.

Even if, for some, seeking justice for sexual violence during conflict might be necessary to begin healing, because it is a painful process and it is sometimes impossible to remember specific details about such traumatic incidents, many sex workers cite the inability to seek justice for these unwitnessed acts of violence— “Now, how can I say who did this? There is no way. What has happened has happened. I don’t know who they were. I feel courageous sometimes, but still I can’t do anything about it. We have become powerless” (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023f).

Where society and the accountability mechanisms have failed them, building their own movements and associations, have enabled sex workers to take back some control of their narratives and their lives, and to seek justice on their own terms. Thakshila, a Sinhala mother of three from Galle, embraces her job as a sex worker. She works in the industry herself, while mobilising sex workers for activism and to support each other because of her own experiences of the lack of social, legal, and physical protection for sex workers. She says “just because they tell us to stop this work, not everyone can [has the ability to] stop it… There are people who cannot work, there are people who don’t have the education. So I do what I can” (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023n).

Sex workers’ narratives show that fear, anxiety, regret, disappointment, anger and pain are shared in equal measure with pride, achievement, care, love, sisterhood and laughter. It highlights how simplistic binaries of right and wrong, good and bad, self-preservation and desperation, helplessness and choice, visibility and invisibility are complicated considerations for sex workers. It highlights how the atrocities of the past have deep resonance in their present realities.

Sex workers, sexual violence, and society

For sex workers who live in the shadow of sexual violence and the broader society within which they exist, three things matter going forward. First, we, as their society, need to not only enable sex workers to share their experiences if they so choose, but to understand their choices and actively listen to their experiences of sexual violence without judgement. Second, we need to build allyships to support sex workers in their activism to recognise sex work as ‘work’, to strengthen their associations, and to amplify their voices in seeking safety and security. And finally, we need to support their efforts to ‘decriminalise’ society’s perception that sex work is illegal. Without challenging the limitations of how the law is applied to sex workers, many women will not consider coming forward to seek justice for conflict-related sexual violence against them in the not-so-distant past.

All this impacts recognising sexual violence on sex workers—especially in situations of transactional or consensual sexual encounters during wartime—as a distinct component of conflict-related sexual violence. The undercurrents of patriarchal views of a woman’s ‘place’ and its impact on the wanton use and abuse of their bodies during times of war, can therefore reinforce structural and systemic violence on women in the long term. The impact of this is felt more broadly than just within sex worker communities or within the duration of the civil war.

Devini, a mother of two with mixed Sinhala-Tamil parentage, born, bred, and still living in Jaffna, who has experienced conflict-related sexual violence firsthand, captures this succinctly, when she advocates for safer, better working conditions without societal judgement as the first steps towards justice.

I will say this, I’ve lived with this for so long. If there is a God, for what happened to me [as a child raped in a camp and the difficult life she has led as a sex worker] they should be punished. This didn’t just happen to me. [It happened to] other little children like me. How many have suffered like this? This wasn’t just getting caught in the crossfire. They knew what they were doing, and for that, there will never be forgiveness… From my experience I am telling you, there should be some kind of status for this job… My life is half over. I’m speaking about the young women, who need a safer space for this work. Even if it isn’t allowed [legalised] it still happens all around. In that case, why not make it a safer place where they can make a dignified living? (Women’s Histories of Sex Work 2023o)

Radhika Hettiarachchi is a public history practitioner, researcher, and curator based in Sri Lanka.

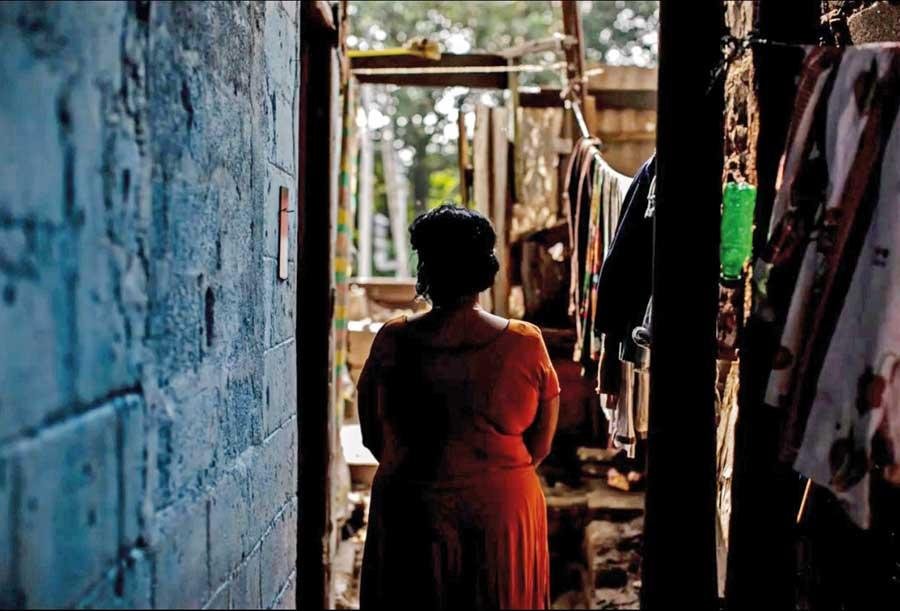

Image source: https://bit.ly/45esRbX

References

Alsalem, Reem. (2024). Prostitution and Violence against women and girls: Report of the special rapporteur on violence against women and girls, its causes and consequences. Human Rights Council, Fifty-Sixth session 18 June–12 July 2024. Available at https://docs.un.org/en/A/HRC/56/48

Brothels Ordinance (No 5 of 1889, as amended by No 42 of 1943). Available at https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/Law%20Site/2-leg_enact_1981/set1/1981Y3V43C.html

Centre for Equality and Justice. (2018). The Social Scar: Stigma Arising from Conflict Related Sexual Violence in Sri Lanka. Colombo: Centre for Equality and Justice. Available at https://cejsrilanka.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Social-Scar-Research-Study-.pdf

De Alwis, Malathi. (2022). “Ambivalent Maternalism: Cursing as Public Protest in Sri Lanka.” Republished in Kanchana N. Ruwanpura, Caryll Tozer, Chulani Kodikara, Sonali Deraniyagala, and Vraie Cally Balthazar (Eds.). Her Smile Lingers – Malathi De Alwis: Selected Essays (128-143). Colombo: International Centre for Ethnic Studies.

De Alwis, Malathi. (2022). “The ‘Purity’ of Displacement and the Reterritorialization of Longing: Muslim IDPs in North-Western Sri Lanka.” Republished in Kanchana N. Ruwanpura, Caryll Tozer, Chulani Kodikara, Sonali Deraniyagala, and Vraie Cally Balthazar (Eds.). Her Smile Lingers – Malathi De Alwis: Selected Essays (174-196). Colombo: International Centre for Ethnic Studies.

Deshapriya, Paba, and Ponni Arasu. (2023). Status of Sex Workers in Sri Lanka: A National Report 2022-2023. Sri Lanka: Sex Workers and Allies of South Asia. Available at https://srilankabrief.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Status-of-sex-workers-in-sri-lanka-2022-2023-EN.pdf

Guterres, Antonio. (2019). Conflict Related Sexual Violence: Report of the United Nations Secretary General (S/2019/280). Available at https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf

International Commission of Jurists. (2021). Sri Lanka’s Vagrants Ordinance No. 4 of 1841: A Colonial Relic Long Overdue for Repeal. Geneva: International Commission of Jurists. Available at https://www.icj.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Sri-Lanka-Briefing-Paper-A-Colonial-Relic-Long-Overdue-for-Repeal-2021-ENG.pdf

Miller, Jody, and Kristin Corbone-Lopez. (2013). “Gendered Carceral Regimes in Sri Lanka: Colonial Laws, Postcolonial Practices, and the Social Control of Sex Workers.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 39 (1): 79-103.

‘Panel discussion on socio-economic challenges and access to justice’ [discussion]. (2023). Public discussion on Women’s Histories of Sex Work in Sri Lanka (12 December 2023, Sri Lanka Foundation Institute, Colombo).

Saibo v. Chellam et al. (1923). New Law Report Vol. 25: 251-253. Accessed at https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/058-NLR-NLR-V-25-SAIBO-v.-CHELLAM-et-al.pdf

SWASA. (2024). Response to the report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls to the UN Human Rights Council. 31 January 2024. Accessed on 10 December 2024. Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1G0F2Fz_0xxE41vaXql7Ml_XrRK9wqJRM/view

Tambiah, Yasmin. (2005). “Turncoat Bodies: Sexuality and Sex Work under Militarization in Sri Lanka.” Gender & Society, 19 (2): 243-261.

Traunmuller, Richard, Kijewski, Sara, and Markus Freitag (2019). “The silent victims of wartime sexual violence: Evidence from a list experiment in Sri Lanka”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63(9) 2015-2042.

Vagrants Ordinance (No. 4 of 1841, as amended by Act No. 2 of 1978). Available at https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/leg_enact_1981/1981Y3V44C.html

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023a). “‘Meena’: I believe there is some God look out for me” (Sin/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (13 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/okhMYUe0Nns?si=dv0X2UVGApluS2xq

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023b). “‘Fathima’: I thought about it. There was no other way. So, I started this work” (Tam/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (28 July 2023). Available at https://youtu.be/Z0Q6AvgMn6c?si=B04S1rwnF6nRi3Y3

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023c). “‘Abhi’: It is for a future that I struggle…” (Tam/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (13 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/UqPXmpvPBDI?si=NtFdMMnj98tJWYMS

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023d). “‘Kamala’: No-one helps a woman without expecting something back…” (Sin/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (28 July 2023). Available at https://youtu.be/CaM-W_j2i3k?si=hcjiLhSsz13WYG2f

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023e). “‘Inosh’: We can’t stay in one place for too long…” (Sin/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (13 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/NvHnyPPOOMU?si=lbnpKGQqbWAK0MxB

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023f). “‘Pushpa’: I feel courageous sometimes…” (Tam/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (7 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/SNTDKwOhFB0?si=98dLHKrwtsprqmz

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023g). “‘Nasreen’: All I hear is the word ‘whore’. We don’t need that…” (Tam/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (28 July 2023). Available at https://youtu.be/IZPDELYj6L8?si=pLZP8mgzstry_usf

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023h). “‘Vishwa’: As the war raged on, our lives got more difficult…” (Tam/ Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (28 July 2023). Available at https://youtu.be/60yKQJXppZQ?si=OeeB04d0aJ_lm_0I

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023i). “‘Luxmi’: Come with me and do what I do…” (Tam/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (28 July 2023). Available at https://youtu.be/KhfH-qD90Hk?si=sDrLjOKIHJO0uGfg

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023j). “‘Kumari’: We can earn well, doing this job…” (Sin/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (28 July 2023). Available at https://youtu.be/y1MU_R0PL1Y?si=A8W2G66FycIcAvsG

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023k). “‘Swarna’: We are easy targets (Sin/Eng)”. The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (28 July 2023). Available at https://youtu.be/IbFmjt94in4?si=TG4WH-V5sW4oUsXm

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023l). “‘Mithuri’: When the Devil drums we have to dance” (Sin/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (13 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/1fgzgf3-k1A?si=dm7yCZRebiT2eoiK

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023m). “‘Thamarani’: I knew since I was ten years old…” (Tam/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (7 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/4ZXd9NuSbj8?si=P13WJefpYaWmZIM1

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023n). “‘Thakshila’: Dignity is our right…” (Sin/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (13 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/E6h6eK2AWzI?si=5b3ixUU6gvcZXyUf

Women’s Histories of Sex Work. (2023o). “‘Devini’: I think we should be allowed to do sex work with dignity” (Sin/Eng). The HerStories Project Sri Lanka. YouTube (13 June 2024). Available at https://youtu.be/e-PZCNVi4lA?si=HPmcU2ONqkgSBE7t

[1] I use the term ‘women’ to refer to those identifying as women, which includes CIS, transgender, and those living as women.

[2] The Women’s Histories of Sex Work are the stories of 35 women from across Sri Lanka, that have worked throughout the war and continue to work to the present day. On the invitation of peers, sex workers participated in the workshops, built relationships with each other across the country and across barriers with the hope of building a movement of their own to support in multiple ways, and documented their life histories. When they shared these stories, they did so primarily because they wanted us, their society, to understand that behind every sex worker is a woman with a real life, real reasons that govern their survival choices, and a real history. Their stories are archived at www.youtube.com/@HerStoryArchives

[3] Acknowledgements: This research and public engagement project has been funded through a small grant from the International Coalition for Sites of Conscience. The International Centre for Ethnic Studies is thanked for supporting the sharing of these research findings for public engagement and advocacy. The editors of Polity are thanked for their helpful suggestions. The research was conducted together with the Grassrooted Trust and Sex Workers and Allies South Asia – Sri Lanka chapter. Sharni Jayawardena, Asanka Rohan, and Yogan Mahadevan are gratefully acknowledged for their photography, videography transcripts, and support in video-editing for the stories archived on the Women’s Histories of Sex Work YouTube channel. I am grateful to Rani Singarajah for providing translations and administrative support; and Praja Diriya Padanama in Puttalam, Stand-Up Movement in Katunayake, Human and Natural Resources Development Foundation (HNRDF) in Galle, Praja Shakthi Surakeemay Madyasthanaya in Monaragala, SWASA-Jaffna for their partnership and Trans-Equality Trust in Peliyagoda. Most importantly, the openness, generosity, and courage of the sex workers across Sri Lanka is admired and appreciated.

[4] There were Sri Lankan and foreign sex workers who were working at the higher end of socio-economic strata, primarily in Colombo during and after the war. However, this article does not focus on their experiences.

[5] The war-affected and war-adjacent areas primarily in (but not limited to) the north and the east, where ethno-religious minority populations (Tamils and Muslims mainly) were numerically dominant and were affected disproportionately by the war. It can be a physical geography/territory or an imagined one linked by shared lived experience, where they and their everyday interactions with systems of governance, service-delivery, access to human rights and redress were characterised by minoritisation and militarisation. During the war these geographies were largely areas without witness for human rights abuses.

[6] However, according to the International Commission of Jurists (2021: 3), “Vagrancy laws created status crimes where the offence is not based upon prohibited action or inaction, but rests upon the identity of the offender who has, or is perceived to have, a certain personal condition or is of a specified character”. This means that ‘being a sex worker’ is not in itself an offence under the law.

[7] “Any person who shall appear, act, or behave as master or mistress, or as the person having the care, government, or management of any brothel, shall be deemed and taken to be the keeper or manager thereof, and shall be liable to be prosecuted and punished as such, notwithstanding that he or she shall not in fact be the real keeper or manager thereof” (Brothels Ordinance 1889). However, it does not mention sex workers working in the brothel.

[8] When arrested, many are remanded until brought before a magistrate, or for 14 days for STI blood tests (which is again police practice rather than provided by law). This treats sex workers as vectors of disease by using healthcare punitively, which in itself is a symptom of structural violence (Deshapriya and Arasu 2023)

[9] The arts-based story-telling tools used are detailed in http://www.about.memorymap.lk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/7_A-Tool-kit-Narrative-History-Documentation-new.pdf

[10] All the names in this article are anonymised to protect the women’s privacy. They are shared here and through the exhibition or website with informed consent, opportunity to validate, and right to withdrawal.

[11] It is recognised that violence perpetrated against male and female bodies may differ and can be asymmetric based on many factors and layers of vulnerability including socially ascribed notions of gender, physicality, values and mores, and class (see Traunmuller, Kijewski & Freitag 2019).

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...