“One day, nobody will even ask about us”: The obsolete silversmiths of Kandy

Hasini Lecamwasam

In the course of research into why the traditional craft economy, despite being a key medium through which Sinhala nationalism is expressed, was not lifted with the rising tide of nationalism and its related economy, I have been interviewing brassware producers and silversmiths as two case studies. My visit to Thalathuoya (about 10 km away from Kandy) first in March 2023 and subsequently a few more times, was an extension of this. My initial point of contact was a government official attached to a Divisional Secretariat (DS) of the area, who kindly introduced me to several of his colleagues, facilitated a group discussion on the premises of the DS office, and then accompanied me – along with one of his colleagues – to a village in their jurisdiction, to speak to a traditional silversmith.

The village I visited was a further 10 km away from Thalathuoya, lying along the Kandy-Nuwara Eliya border. Nestled in lush mountains peppered by plots of land used for seasonal cultivation, the riveting beauty of the area is in stark contrast to the poverty plaguing many lives there. Nearer the main road, as is usually the case, we found the houses of families that were clearly well-off, while the poorer households were further interior. We reached a stream (artificially created, I later learnt, through the Murapola Ela irrigation scheme of 1945) that sloshed down the steep landscape to the paddy fields below, irrigating them. From there, we descended the stone steps running parallel to the stream, to reach the house of our host that lay at the end of the descent, surrounded by paddy fields.

He is in his late sixties, and greeted us with much warmth, indicating the close relationship he shared with the two men travelling with me. The three later revisited memories of how they first met each other, when the young officials were newly appointed to the area, and the subsequent strengthening of their ties over months of regular interaction. My informant is a traditional artisan and the president of the village artisans’ collective, as well as the farmers’ association.

He started the conversation off with a description of the feudal past of the village, which had apparently been established during the time of King Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe. Folklore has it that the ruler in disguise had spent the night at an artisan’s home in this area. The silversmith, upon learning the true identity of his guest (having taken a close look at his belongings and spotting the royal emblem on the sword), had secretly placed a ring with a blue stone on the latter’s toe while he slept, as a token of recognition and respect. In return, the King had granted him all the surrounding landholdings, thus giving rise to the village. In the past, shared our host, the artisan village was surrounded by cultivators who would provide for that village. Even today, this village continues to be the only one in the area where members of the artisan caste community reside, while all the surrounding villages are populated by those of the Goigama caste, who continue to predominantly engage in agriculture, with a few exceptions of state sector employees, according to a respondent from a neighbouring village.

In recent times, the Murapola Ela irrigation scheme has facilitated greater diversification of income generating activities for the village, with more and more people of the traditional silversmith caste – known as Navandanna, referring to artisans in general – taking up agriculture. With the opening of the economy, our host opined, further avenues emerged for income generation, leading to many youths taking them up, gradually resulting in an ongoing process of disintegration of the craft-based village.

Discussions with other artisans who have flourished in the business of traditional silver jewellery making shed light on exogenous factors that also contribute to this state of affairs, such as political patronage and consequently the rise of middlemen who suck in much of the profit generated.

Within this context, my informant lamented the fast decline of his craft, framing it in a narrative of cultural erosion.

The entry point to this discussion was the transformation that the ‘open economy’ policy has wrought in his industry: “They [non-traditional vendors selling similar items] started importing cheap substitutes for the raw material that we use for our products, and so were able to sell similar looking jewellery for much less. Then they started wholesale importing the jewellery themselves, imitation ones, from India and China, which were much cheaper. So, people started going for those. They are much shinier, their shine is much longer lasting. The chemical mixes they use to obtain those qualities are poisonous to the body. People will one day realise the actual cost of our industry being pushed out of existence. In another two to three years there would be no point in coming to these villages. Nobody will even ask about us.”

He then recalled an instance in which he had stepped in to negotiate on behalf of the village with a domestic tourism operator. Their representatives had visited the village, expressing interest in working with the crafts people there to “tap into the tourism potential of the area”. This company had proposed conversion of the village households into homestays where the guests could experience for themselves the traditional production process of silver jewellery. Guests were to be transported into the village by bullock carts driven by their respective hosts — our subject was thoroughly amused by this, laughingly saying “As if the natural incline of the land wasn’t hard enough to climb by ourselves!” In exchange (and in addition to whatever tips the guests would make to the host family), the company had promised to construct a new house for each participating household, which it could choose from among four or five such models.

The catch – unsurprisingly there was one – was that all home owners had to transfer ownership of their property to the company! The promise of new income had clouded the good reason of the villagers, he shared, which had to be hammered back into them. Using his authority as the village patriarch, he had refused to have any further negotiations with the company, much to the dismay of many cash-strapped villagers, particularly the young ones.

This also led us to the question as to why the youth are not keen on continuing in artisanal work anymore. The associated caste connotations are an obvious deterrent. The issue is compounded by the additional challenges faced by artisans such as the lack of institutional continuity of government promotional initiatives, in-fighting between the State institutions governing the crafts[i], profiteering by middlemen to the detriment of direct producers, the benefits of political patronage mostly having eluded this community etc., which together render it economically untenable to make a livelihood out of cottage industries. One has to also keep in mind exogenous factors such as the opening up of other, in some cases more ‘prestigious’, avenues of income such as State sector employment. More recently, quick cash options in the informal sector like driving three wheelers, construction work, and work in garment factories (mostly for women) have also encouraged many young people to venture away from artisanal work. Subsequent visits yielded that commercial agriculture is now the chief livelihood of many youth in the village, who mostly supply for the Colombo market and, in a limited number of cases, those abroad. A desperate attempt at income generation was also observed in the form of a shoe making business that has now been abandoned, due to the sheer impossibility of connecting with a market.

This narrative of decline, however, needs to be complicated by another conversation I had with my initial contact, the DS official. Also a resident of a nearby village, he was somewhat critical of the insistence of traditional artisans on “doing things the traditional way”, particularly in terms of the scale and speed of production, which he believed could immensely benefit from mechanisation: “You can retain the content and update the method. But they refuse even to do that. For them, how you produce it is also part of ‘the tradition’ and therefore what the end outcome actually means. I am also from this area, and I want the best for them. If they hold on to these notions, you can’t avoid their industries getting completely wiped out.”

What inhibits the adaptation of pre-capitalist craft industry to the logic and rationality of 21st century capitalism? Is there a future for those in the crafts sector outside of producing artefacts for foreign tourists? If, in fact, they do ‘upgrade’ to newer methods of production, can they claim to be ‘traditional’ anymore?[ii] And what implications will this have for the niche market they have carved out for themselves, inadequate as it may be? Without demand from society for the products of their skill and labour, will the silversmiths abandon their trade and sell their tools to be exhibited in galleries or the homes of wealthy collectors?

Hasini Lecamwasam is lecturer at the Department of Political Science, University of Peradeniya.

Notes

[i] Laksala, Design Centre, and National Crafts Council.

[ii] For a comparative perspective, see Balaswaminathan, Sowparnika. (2018). “The Real Thing: Craft, Caste, and Commerce amidst a Nationalism of Tradition in India”. The Journal of Modern Craft, 11(2): 127-141.

You May Also Like…

Sri Lanka’s Pre-Presidential Election Politics: Uncertainty or Turmoil?

Jayadeva Uyangoda

The coming few months have the potential to produce major political changes in Sri Lanka. The presidential election is...

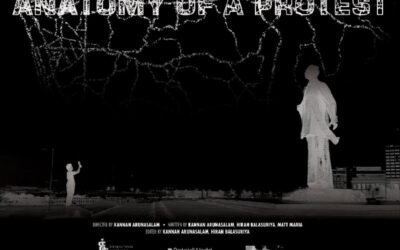

Anatomy of a Protest and Aragalaya Cinema

Hiranyada Dewasiri

The 2022 people’s uprising and occupation movement in Sri Lanka, widely known as the Aragalaya, was heavily documented...

The conjuncture in the crisis

B. Skanthakumar

“Aaranchiya Subhai!” (‘Await Good News’) read posters plastered across the country recently. It was the build-up to...