Magic Maids: Sweeping Up a Storm at the Sorbonne

Nadeera Rajapakse

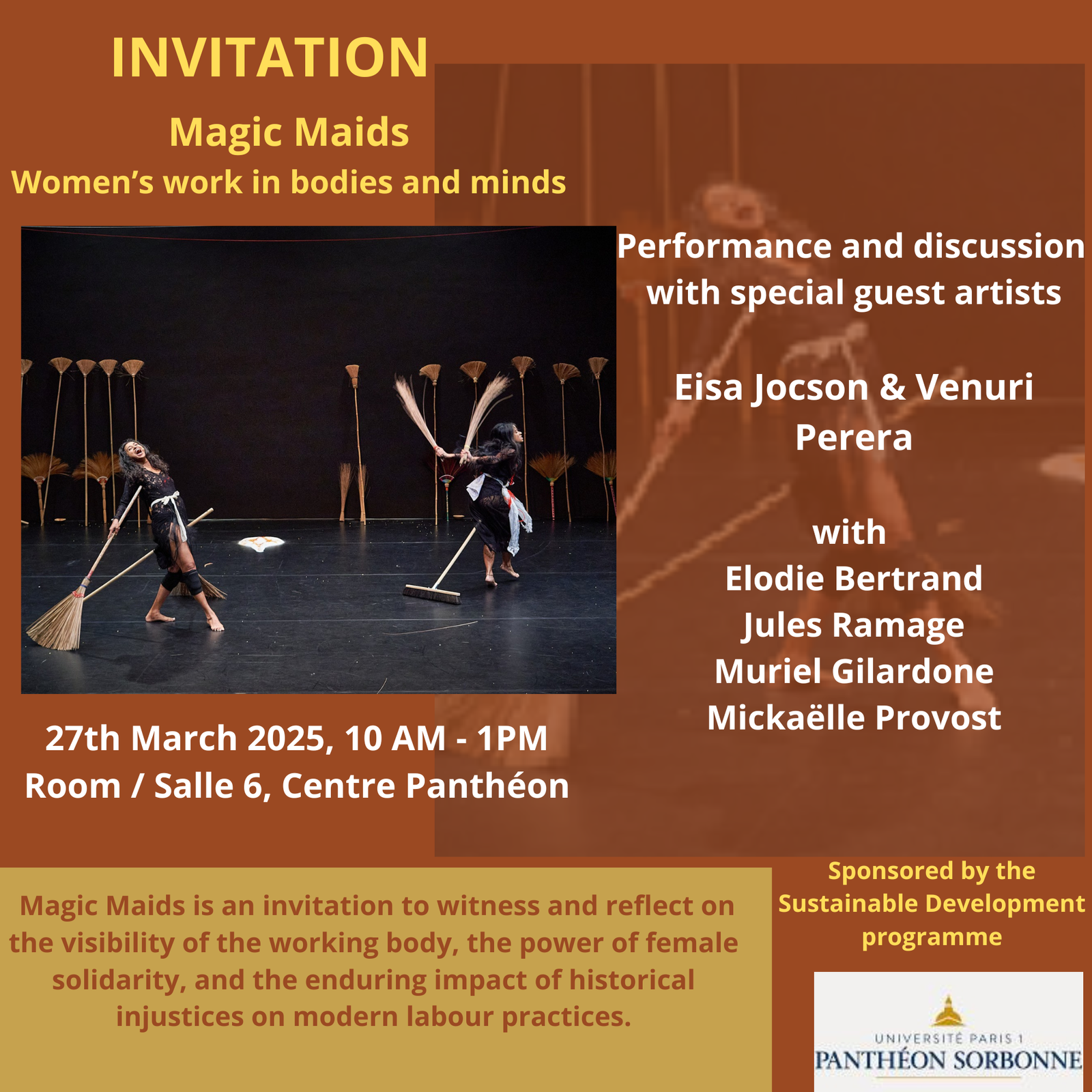

After performing in several theatres across Paris, Eisa Jocson and Venuri Perera bewitched the spectators, students, and startled passers-by at the Pantheon Centre of the University Paris 1, Pantheon-Sorbonne in March 2025. They swept through the halls of the 18th century building, housing the second oldest university in Europe, to embody women migrant domestic workers.

Venuri Perera and Eisa Jocson at the University Paris 1, Pantheon-Sorbonne

Photo credit: Jean-Remy Mallek

Their representation was hailed by an eager audience of economists, historians, philosophers, political scientists, anthropologists, geographers, working on and interested in various related subjects. A roundtable session among scholars and artists, bound by common themes of female labour, exploitation, and agency, was followed by a general discussion between the two dancers and guests.

Among the many compelling insights shared, one particularly resonant idea was that the deepest intellectual understanding often arises through embodied experience. In the novel Expectation, the author describes how this can happen: “suddenly the knowledge arrives, hitting her body before her mind. It spikes her blood, makes her heart race, her palms damp” (Hope 2019: 251). Accordingly, in Magic Maids, resistance is articulated through movement, the dancers physically and symbolically reclaim the figure of the domestic worker. In the following commentary, I will discuss the idea of resistance, its significance in this context, and the narrative power of the performance in reclaiming the idealised image of women.

Roundtable discussion with Emmanuel Charrier (moderator), Jules Ramage (visual artist), Muriel Gilardone (economic historian specialising in gender and economics), Mickaëlle Provost (philosopher), Elodie Bertrand (economic historian, editor of Routledge Handbook of Commodification).

Photo credit: Jean-Remy Mallek

Firstly, resistance comes in the shape of exposing the disturbing aspects of migration for domestic work. For one, the fundamental contradiction structuring Sri Lanka’s migration economy: the systematic social devaluation of women’s domestic labour against its staggering economic contributions. The state’s reliance on 8.4 billion USD in annual remittances, of which 54% are from domestic workers (CBSL 2023), exists in violent tension with cultural imaginaries that render these workers as ‘demure’, ‘docile’, and ‘disposable’, while being remittance-sending ‘heroines’.

The aesthetic framing of domestic workers as ‘smiling, docile’ figures emerges from deep cultural constructs. The ideal female figure in religious, nationalist, and cultural tropes lacks agency, existing in submission to men or gods (Sreenivasan 1975, de Mel 2001, de Silva 2004). Added to that is a narrow version of “purity” as well as “pedagogies of respectability” (de Alwis 2022). This has translated into general media representations where most Sri Lankan newspaper articles frame migrant workers mostly as either “victims” or “heroines” (Rata Viruwo in Sinhala), denying complex subjectivity. This is just like the female ideal in certain religious representations: they are either pure, chaste, and submissive, or they are all-powerful, destructive goddesses. The Vessantara Jātaka’s ideal of female self-sacrifice finds an echo in the state rhetoric celebrating “heroines” sending remittances, making resilience and silent endurance the most acclaimed qualities in “good” maids (de Silva 2004).

In keeping with economic market logic, the supply of migrant labour is endless, coming from many South Asian nations competing with one another, whereas demand from employers (mostly in the Middle East) powerfully dictates all terms of employment. Hence, women migrant workers are disposable, easily replaceable. The dancers, Jocson and Perera, recount discovering “24 nails driven into her body, like a living voodoo doll”, referring to a real experience of a migrant worker. Again, the contradiction is made obvious: the horrific exploitation of bodies that literally constitute the nation’s economic lifeline. Sri Lanka’s 1.2 million migrant domestic workers generate about 30% of total remittances, 6.7% of GDP (World Bank 2023). And yet, the institutional recognition of the value of their labour remains an uphill struggle: only in 2020 was the promise made to upgrade domestic work to the skilled labour category (Mudugamuwa 2020), while standard employment contracts under the Foreign Employment Act, and ILO Convention 189 ratification still do not take full account of domestic work.

Venuri Perera and Eisa Jocson shedding docility, resisting purity.

Photo credit: Jean-Remy Mallek

These institutional failures mirror the “social reproduction paradox”, i.e., the simultaneous economic reliance on and symbolic annihilation of care work under financialised capitalism (Elson 2012). In the course of their performance, Jocson and Perera narrate: “even if you hit her, she may say ‘hit me baby, one more time’”, laying bare the paradox where ‘docile’ workers must be simultaneously productive enough to remit and disposable enough to replace.

Another revelation from the duo is about racialised market hierarchies. The performance’s mocking comparison between “a Filipina” and “a cheaper Sri Lankan” exposes what Bridget Anderson (2000) terms “hierarchies of servitude” in global care chains. Recruitment agencies actively cultivate this in terms of salary differentials: a Filipina worker is paid double the wage received monthly by a Sri Lankan domestic worker in many Middle Eastern countries (Esim and Smith 2004); skills framing: Most Sri Lankan agencies advertise workers as “more submissive and easier to mould” vs. Filipinas as commanding “more respect” (Jureidni and Moukarbel 2004: 6). Above all, “Sri Lankan” or “Sri Lanki” is synonymous with domestic worker, so much so that if the domestic worker is from the Philippines, the question would be “Is your Sri Lankan a Filipina?” (Jureidni and Moukarbel 2004: 5). Jocson and Perera rephrase the question for the French audience (and French employers), asking where their “Sri Lankan” is from: Algeria? Romania? The Republic of Guinea?

Discussing embodied resistance: dancers and participants at University Paris 1, Pantheon-Sorbonne.

Photo credit: Leonie Seince, Maya Abou Imad, Iris Chaput, Lucie Liu

The devaluation of migrant workers is seen in other disturbing institutional shortcomings and exclusions. While Sri Lanka’s economic crisis has intensified reliance on migrant earnings—remittances cover 128% of the trade deficit according to the Central Bank (CBSL 2023)—the 2023 national Budget allocated only a paltry amount to migrant welfare; only a handful of returnee workers access reintegration programs (IOM 2023) and the majority of migrant households do not use bank accounts, especially for remittances. Most have no pension contributions despite working close to a decade abroad (ILO 2021).

On the other hand, restrictive regulation is palmed more on migrants than on markets. In the SLBFE curriculum, mandatory household training encourages submission (Handapangoda 2023, Jureidni and Moukarbel 2004). There are bans on pregnancy, marriage (Ireland 2018), and unionisation (Amnesty International 2025), while non-payment of wages, non-compliance with labour laws, and non-respect of basic worker rights go unpunished.

By framing domestic work as ‘natural’ feminine traits rather than skilled labour, global labour markets exclude them from formal economic accounting. Then the idealised yet paradoxical requirements are piled on: maids need to perform docility and as a result, suppress emotions for job security. They need to channel productivity to super-human levels: An average workday in Gulf Cooperation Council countries is 17 hours (ILO 2021), which they endure stoically, leading to chronic health conditions.

Lynch documents how Sri Lankan migrant workers face “moral censure for transgressing spatial boundaries” (2007: 92), stigmatised as “fallen” women for monetising domesticity while remaining culturally obligated to perform it, unpaid, at home. These contradictions add up, with the state praising women’s economic contributions while denying them labour rights, which Jayawardena describes as “patriarchal ventriloquism” (2016: 24).

Venuri Perera, wielding the brooms wildly

(Still from video footage)

Credit: Leonie Sence, Iris Chaput, Maya Abou Imad, Lucie Liu and Theo Milon

But then, the Magic Maids strike. Jocson and Perera viscerally demonstrate that the same bodies disciplined into docility can erupt into wild, powerful dancing, symbolising the latent agency within apparent submission. This agency becomes discernible, palpable, when we shed the gendered, capitalist lenses above. Despite moral, physical, and institutional risks, which are well-documented, Sri Lankan women continue migrating at unprecedented rates.

This constitutes not merely economic pragmatism, but a strike against the gendered, spatial order. Migrant women transmit subversive “gender remittances” (Levitt and Lamba-Nieves 2011) that slowly corrode patriarchal ideology in sending communities. These narratives weaponise the very mobility that moralists decry. Their efforts have led to movements, like the ILO C189 campaign, which have forced recognition of domestic work as skilled labour providing potent examples of “capability metrics” (Piper 2017). In Sri Lanka, returnee workers now demand pension contributions, not as supplicants, but as creditors of a national economy that they sustain.

By migrating to take up work that challenges traditional ideals of domestic femininity, and through subtle defiance of religious or moral ideals that confine them to obedience and purity, women migrant domestic workers show resistance.

The performance epitomises the central contradiction: these women are economically indispensable, yet socially expendable. Their labour props up GDP while their contribution is undervalued, a paradox sustained by gendered architectures. Yet as the performance’s climactic shift from slow, robotic sweeping to wails, vigour, and piercing eye contact reminds us, even the most disciplined bodies harbour the capacity to disrupt the scripts written upon them. The true measure of feminist praxis lies not in lamenting oppression, but in tracing, as this commentary has attempted, the fault lines where agency erupts through the cracks of constraint.

Venuri Perera, defying norms of docility

(Still from video footage)

Credit: Leonie Sence, Iris Chaput, Maya Abou Imad, Lucie Liu and Theo Milon

Nadeera Rajapakse is an assistant professor at the University of Paris 1, Pantheon-Sorbonne in the History of Economic Thought and in English for Economics. She is a member of the PHARE (Philosophy, History and the Analysis of Economic Representation) research department and her current areas of research include development and identity, women migrant domestic workers, and migration and identity.

References

Amnesty International. (2025). Locked In. Left out. The Hidden Lives of Kenyan Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia. London: Amnesty International. Available at https://www.amnesty.nl/content/uploads/2025/05/Amnesty-Kenya-Saudi-workers.pdf?x69908

Amnesty International. (2014). “My Sleep is My Break”: Exploitation of Migrant Domestic Workers in Qatar. Available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde22/004/2014/en/

Anderson, Bridget. (2000). Doing the Dirty Work? The global politics of domestic labour. London: Zed Books.

Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL). (2023). Annual Economic Review. Available at https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/publications/economic-and-financial-reports/annual-economic-review/annual-economic-review-2023

De Alwis, Malathi. (2022). “The Production and Embodiment of Respectability: Gendered Demeanours in Colonial Ceylon”. In Kanchana Ruwanpura, Caryll Tozer, Chulani Kodikara, Sonali Deraniyagala, Vraie Cally Balthazar (Eds.). Her Smile Lingers. Malathi de Alwis Selected Essays. Colombo: International Centre for Ethnic Studies.

De Mel, Neloufer. (2001). Women & the Nation’s Narrative: Gender and Nationalism in Twentieth-Century Sri Lanka. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

De Silva, Neluka. (2004). The Gendered Nation: Contemporary Writings from South Asia, London: Sage.

Department of Technical Education and Training. (2023). National Competency Standards (NCS) Catalogue. Colombo: DTET. Available at http://www.dtet.gov.lk/nvq_standards

Elson, Diane. (2012). “Social Reproduction in the Global Crisis: Rapid Recovery or Long-Lasting Depletion?” In Peter Utting, Shahra Razavi, and Rebecca Varghese Buchholz (Eds.). The Global Crisis and Transformative Social Change (63-80). Palgrave Macmillan

Esim, Simel, and Monica Smith (Eds). (2004). Gender and Migration in Arab States. The case of domestic workers. Beirut: International Labour Organization. Available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/gender-and-migration-arab-states-case-domestic-workers

Handapangoda, Wasana. (2023). “Migrant domestic workers in the Arabian Gulf”. Ingenere (2 February): https://www.ingenere.it/en/articles/migrant-domestic-workers-arabian-gulf

Hope, Anna. (2020). Expectation. Black Swan.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2023). “Chapter 5 – Migrant-facing Information Initiatives”. In IRIS Handbook for Governments on Ethical Recruitment and Migrant Worker Protection. IOM, Geneva. Available at https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/pub2023-034-l-iris-handbook-for-govt-ch5.pdf

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2021). Making Decent Work a Reality for Domestic Workers: Progress and Prospects Ten Years after the Adoption of the Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189), Geneva: International Labour Organization. Available at https://www.ilo.org/publications/major-publications/making-decent-work-reality-domestic-workers-progress-and-prospects-ten

Ireland, Patrick. (2018). “The limits of sending-state power”. International Political Science Review 39 (3): 322-337.

Jayawardena, Kumari. (2016). Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. New York: Verso Books.

Jayawardena, Kumari and Rachel Kurian. (2015). Class, Patriarchy and Ethnicity on Sri Lankan Plantations: Two Centuries of Power and Protest. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Jureidni, Ray, and Nayla Moukarbel. (2004). “Female Sri Lankan domestic workers in Lebanon: A case of ‘contract slavery’?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30 (4): 581-607.

Levitt, Peggy, and Deepak Lamba-Nieves. (2011). “Social Remittances Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37 (1):1-22.

Lynch, Caitrin. (2007). Juki Girls, Good Girls: Gender and Cultural Politics in Sri Lanka’s Global Garment Industry. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Piper, Nicola. (2017). “Migration and the SDGs.” Global Social Policy, 17 (2): 231-238.

Sreenivasan, M.A. (1975). “Panchakanya – An Age-old Benediction”. In Devaki Jain (Ed.). Indian Women (51-58). New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, India.

Mudugamuwa, Maheesha. (2020). “Skills development for domestic workers. From Housemaid to Housekeeping assistant”. The Morning (23 September): https://www.themorning.lk/articles/98732

World Bank. (2023). “Personal remittances, received (% of GDP) – Sri Lanka”. World Bank Open Data – Sri Lanka. Available at https://data.worldbank.org/country/sri-lanka

You May Also Like…

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...