Queer Representation in Sri Lankan Media: A Double-Edged Sword?

Kasun Kavishka

Queer[1] representation in the media is a polarising topic that has sparked many debates in recent years, revealing its transformative powers as well as its potential pitfalls in the LGBTQ+ movement’s quest for rights, inclusivity, and visibility. Media representation has the ability to define what is considered normal and true, how one looks at oneself and at others, by producing and reproducing existing social hierarchies; in other words, it shapes the collective psyche of the people. In countries like Sri Lanka where the public discourse is predominantly conservative and heteronormative and the intolerance toward queer individuals materialises as cultural resistance to western imperialism, queer representation has an important role in destigmatising sexual and gender identities that transcend the traditional heteronormative binary standards in society.

However, the current state of queer representation in Sri Lankan media makes one question whether it adequately represents the diverse queer experiences shaped by the country’s social, legal, and economic context, or if it is simply limited to stereotypical narratives.

Intolerance towards queer individuals in Sri Lanka

In 2025, Sri Lanka saw the emergence of a ‘mothers movement’[2] that is campaigning vehemently against promoting queer rights in the country. Popular opinion is either that queer rights is a Western agenda trying to destroy local traditions and culture, which are believed to be rooted in heteronormativity and binary identities, or that it is a mental illness that needs to be treated by medicine or therapy (EQUAL GROUND 2021: 57-66).

Ironically, despite the labelling of the LGBTQ+ movement as of Western derivation, it was the British that introduced the laws that discriminate against the LGBTQ+ community in 1883 as part of a broader move to enforce Victorian moral standards in the ‘uncivilised’ colonies. Consequently, even though transgender individuals are allowed to change their legal gender since 2016, the Sri Lankan legal system still penalises adult same-sex consensual relationships as well as other non-normative sexual and gender identities (Wijewardene and Jayewardene 2019: 138-141).

The negative perception of the majority of the population as well as criminalisation under the law have placed the LGBTQ+ community in an extremely vulnerable position in Sri Lanka. They become victims of verbal and physical harassment, and are deprived of necessary medical facilities and of access to legal assistance. It is clear that this general intolerance towards the LGBTQ+ community has impacted the quality and the quantity of queer representation in the country’s media.

The importance of queer representation

Before exploring the issues associated with current representation, it is important to understand why queer representation matters to both members and non-members of the queer community. Queer visibility in the media can either challenge or reinforce existing prejudices about queer individuals. For instance, since the majority of queer representation in media is centred on Western contexts due to the global reach of Hollywood and as well as the relatively greater progress the LGBTQ+ movement has made in Western countries, it has created a homogenised, Western-centric understanding of queer identity while also reinforcing the narrative that the LGBTQ+ movement is Western woke propaganda or homo-imperialist rather than a social movement promoting equality, dignity, and respect (Browne 2022).

Paired with that, the inadequate Sri Lankan queer representation in the media could insinuate that queerness is alien to Sri Lankan society; a misconception that could be challenged if there was more Sri Lankan queer representation. Representation can actively remove the ‘otherness’ associated with queer individuals. Further, representation is helpful to individuals who are still discovering their sexuality, as it would reassure them that it is neither wrong nor shameful if their natural inclination does not conform to the heteronormative binary culture that is considered “normal” in society. As Craig et al (2015) points out, positive queer representation can ultimately be “a catalyst for resilience”, especially for queer youth. Hence, representation contributes to creating a positive and healthy space for everyone.

Misrepresentation of queer identities

Even though queer representation should ideally aim to normalise the LGBTQ+ community within society and promote their social acceptance and equality, it can sometimes be self-defeating. This manifests in Sri Lankan media mainly through the misrepresentation of queer identities and bad journalism.

First, let’s consider how queer identities are misrepresented in Sri Lankan media. The impact of deliberate misrepresentation of queer identities in the media is often undermined without taking into account how it shapes the public perception of queer individuals.

For instance, the tendency to portray queer characters only as comic relief or predatory villains, where they become caricatures of existing stereotypes and prejudices, reinforces society’s negative attitudes about the queer community, which ultimately harms the lived reality of queer individuals. In other words, queer identity is reduced to an object of ridicule, contempt, fear, and caution. The popular way of making queer characters comic relief is exclusively presenting queer men with effeminate characteristics and queer women with masculine characteristics. A prime example of this is the popular Sinhala movie Sikuru Hathe (“Venus at Seven”) which featured two flamboyant men as comic relief (Devasurendra 2020). Their character tropes were built on the stereotype that all flamboyant men are homosexual, and not conforming to traditional and ‘socially expected’ gender and sexual norms is comical.

Another instance where the stereotypical queer character trope is used is in the novel Giraya (“Betel Nut Cracker”) (1971) by Punyakante Wijenaike. It is one of the earliest Sri Lankan novels to deal somewhat openly with queer identity through the character of Lal. However, in this novel, Wijenaike resorts to a conventional and prejudiced view of the community by presenting homosexuality as unnatural and a perversion that goes against the sacred Sri Lankan culture that champions heteronormativity. Later, when Wijenaike’s novel was adapted into a tele drama directed by Lester James Peiris, Lal’s homosexuality was completely removed from the narrative, demonstrating the impact of local traditions on LGBTQ+ representation in media. As Mala de Alwis points out, “by erasing a reality of life such as homosexuality/lesbianism, our film and teledrama directors do us a great disservice” (1993: 33). This attempt to fit the diverse gender and sexual identities in the LGBTQ+ spectrum into a prescribed mould undermines the community’s emancipatory efforts, ultimately creating a monolithic queer characterisation that fails to represent the real diversity among LGBTQ+ individuals.

However, there are also instances of positive queer representation in Sri Lankan media. Shyam Selvadurai in his debut novel Funny Boy (1997) explores the complexity of non-normative sexual identities and the external as well as internal struggles faced by queer individuals when coming to terms with their sexual and gender identity through the character of Arjie. In the novel, Arjie’s inability to comply with the ‘masculine’ gender role that patriarchal society expects him to perform leads him to be labelled as “funny”. He eventually internalises this sentiment that later haunts him after his first sexual encounter which he perceives as a “dreadful act”. So, Selvadurai’s book spreads awareness about the queer community and humanises them, by showing how the “lajja-baya”(shame-fear)[3] culture and the erasure of LGBTQ+ identities in popular discourse in Sri Lanka creates an internal conflict within queer individuals inhibiting their ability to accept their own identity (De Costa 2020: 34-36). This highlights the necessity of more positive queer representation in Sri Lankan media to eliminate the stigma and shame associated with queerness.

Funny Boy is often taught as a part of English Literature curriculum in Sri Lankan universities, and interestingly, research reveals that students’ reception of Arjie’s queerness is often tied to his victimhood rather than his queer desires and educators rely on the victim trope to approach this “difficult knowledge”[4] (De Costa 2022). While highlighting the socio-cultural limitations when approaching queerness in public discourse, this raises the question of whether positive queer representations in Sri Lankan media overly rely on the victim trope to make queerness more palatable to a wider audience, as explorations of queer desire are often met with societal resistance and discomfort.

Similarly, Visakesa Chandrasekaram’s film, Sayapethi Kusuma (Frangipani) (2014) which features a love triangle between a woman and two men can be considered one of Sri Lanka’s first full-length Sinhala LGBTQ+ movies. Chandrasekaram uses this film to explore the lived reality of LGBTQ+ individuals in Sri Lankan society who are forced to hide their identity in fear of the law and public ridicule. Through the character of Chamath, it delves into the unique tension between queer identities and the two dominant ideals of masculinity rooted in Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism, i.e., being a monk or a soldier. As Chandrasekaram himself has said, “The reason I positioned this character (Chamath) between those two was to symbolically assert his existence. He has a right to be there between them” (Illanperuma 2016).

However, despite being one of the rare instances where LGBTQ+ identities are positively represented, it was only screened in two venues in Sri Lanka due to censorship rules, preventing it from reaching a larger audience within the country. Although there are no legal regulations that directly prevent LGBTQ+ content from appearing on mainstream media, censorship of content in Sri Lanka is arbitrary and based on personal biases (Prescilla, Mendis, and Jayasinghe 2021). Arbitrary censorship of LGBTQ+ content in Sri Lankan media is a threat to queer visibility in Sri Lanka. It is a significant obstacle to spreading awareness about the LGBTQ+ community and engaging in discussions to find solutions to improve inclusivity at a structural level.

In contrast, Donald Jayantha’s film Maya (2016) occupies an ambiguous space between stereotypical and progressive Sri Lankan queer representations. The titular character of the movie is a transgender woman and towards the end, the movie features a flashback which reveals her tragic backstory of being disowned by her own family for being transgender and her forgone dreams of becoming a doctor. The film is progressive in the sense that it moves away from the conventional depiction of transgender persons only as sex workers and its bold commentary on bigoted societal attitudes towards transgender individuals.

However, as Ibrahim and Kuru-Utumpala (2016) point out, this movie reproduces the damaging stereotype that queer people are possessed or cursed by spirits and need to be exorcised or cured. Hence, while addressing the issues of transphobia in Sri Lankan society, Maya also stereotypically portrays transgender people as ‘freak shows’ to be feared, pitied and tolerated. The phenomenon identified as “anxious displacement”[5] by Andre Cavalcante (2015), can be observed in this instance, where, in the simultaneous effort to legitimise queer representation and create a queer narrative palatable to the mainstream, existing social hierarchies and stereotypes were ultimately reproduced (Thomson 2021).

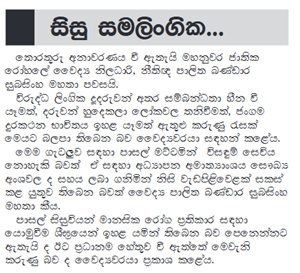

On another note, the practice of bad journalism where news involving or related to the queer community is often reported in biased ways is another form of negative representation. This is seen in Sri Lankan media through news articles that contain disinformation and misinformation often emphasising the purported incongruence between queerness and Sri Lankan culture and its assumed harm on children. For example, a news article in the Divaina newspaper (January 26, 2025) titled “සිසු සමලිංගික සබඳතා වැඩිවෙලා” (“Same sex relations between students have increased”) presented queerness as a mental illness caused by increasing loneliness and isolation among school students. Not only does this article promote the misconception that homosexuality is a mental illness, it also suggests that it is a personal choice. Unfortunately, this is just one of many bigoted and ignorant articles about the queer community in Sri Lanka.

Figure 1: Article published in Divaina on 26 January 2025

Improving queer representation

It is evident that Sri Lanka still has a long way to go in terms of improving queer representation in the media. To begin with, even though there are portrayals of queer women and AFAB[6] transgender persons in works like Ameena Hussein’s Blue: Stories for Adults (2010) and Asoka Handagama’s Thani Thatuwen Piyabanna (“Flying with One Wing”) (2003), the overall representation of queer identities other than queer men is relatively less. Hence it is quite poor in capturing the true diversity of the Sri Lankan queer community.

Further, when looking at ways to improve queer representation, it is important to consider the cautionary tales from other countries and not fall into the traps of tokenisation and one-dimensional character tropes. Tokenisation is a result of the commodification of activism. While “pink dollar” activism can be effective when raising awareness about the queer community, it has also adopted the LGBTQ+ movement as a throwaway marketing tactic, used during the month of June by performatively plastering everything with rainbows.

As Bain and Podmore (2023) smartly put it, this “rainbow infrastruggle” and “rainbow aestheticisation” often prioritise projecting a ‘progressive’ aesthetic instead of fostering actual social change. While some of these tokenised representations are not entirely negative, their lack of nuance gives them a forced and propagandistic similitude, hence, giving the entire movement a likeness to propaganda. This is manifested in online spaces through performative allyship by some supporters of the LGBTQ+ community, whose activism is confined to posting on social media (including rainbows) during Pride month, reducing the entire LGBTQ+ movement to aesthetics and symbols. In this form of ‘activism’, the LGBTQ+ movement and queer representation are commodified as a product that is marketed to appease a certain demographic, creating a façade of perceived equality while the discriminatory status quo remains unchanged. This is a cautionary tale on the limitations of using consumerism for social activism.

In addition, the tendency to portray one-dimensional queer identities that do not develop beyond sexuality and the struggles of queer individuals can also be damaging. The media’s obsession with either hypersexualised narratives or tragic stories, i.e., stories that exclusively revolve around the struggles and discrimination faced by queer individuals because of their sexual and/or gender identities also contributes to creating a shallow understanding of the queer identity. When the focus is always on eroticism, it reinforces the prejudices of queerness being an identity based purely on sexual behaviour rather than as a multifaceted identity that involves deep emotional bonds and relationships.

Similarly, while it is important to present tragic stories as they spread awareness about the unique struggles faced by queer individuals in a society that does not fully accept them, presenting only tragic stories once again narrows the identity of queer individuals to their sexuality and the struggles that transpire because of it. Sympathy is a good stepping-stone to improve inclusivity in society, but queer individuals should not be accepted because one feels sorry for them. Rather, they should be accepted because they are human and deserve to be treated with respect like everyone else.

Queer representation: A double-edged sword?

In essence, queer representation in the media can be a double-edged sword. It is a crucial tool when normalising queer identities and breaking down the taboo attached to them especially in countries like Sri Lanka where queer visibility is threatened culturally and politically. However, it also runs the risk of either propagating existing harmful stereotypes or creating a monolithic queer identity that undermines the true diversity within the community. Hence, the focus should be on creating new ways to celebrate queer identities that seek to do more than merely induce pity; representations that do not fall into the trap of commodification or Eurocentrism; and, most importantly, representations of reality, where LGBTQ+ members are more than the rainbow aesthetic. Finally, while positive queer representation is important, it is not and should not be the sole solution to the discrimination and struggles faced by queer individuals. Representation can only go so far to address the structural violence and inequalities experienced by the LGBTQ+ community.

Kasun Kavishka is an undergraduate at the University of Colombo, and an intern at the Social Scientists’ Association.

Image credit: Kasun Kavishka

References

Bain, Alison L., and Julie A. Podmore. (2023). “Rainbow Infrastruggles: The Infrapolitics of LGBTQ+2S Surplus Visibility in Suburban Infrastructure.” Journal of Urban Affairs, 47 (2): 1–23.

Browne, Jenia. (2022). “The Complexities of Queer, Caribbean Identities, and the Dangers of West-Centric LGBTQ+ Advocacy.” Northeastern University Political Review (3 February). Available at https://nupoliticalreview.org/2022/02/03/the-complexities-of-queer-caribbean-identites-and-the-dangers-of-west-centric-LGBTQ+-advocacy/

Cavalcante, Andre. (2015). “Anxious Displacements: The Representation of Gay Parenting on Modern Family and The New Normal and the Management of Cultural Anxiety.” Television & News Media, 16 (5): 454-471.

Chandrasekaram, Visakesa. (2014). Frangipani (‘Sayapethi Kusuma’). Havelock Arts.

Craig, Shelley L., Lauren McInroy, Lance T. McCready, and Ramona Alaggia. (2015). “Media: A Catalyst for Resilience in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth.” Journal of LGBT Youth, 12(3): 254–275.

De Alwis, Mala. (1992). “Giraya: the harsh grip of a dialectic.” Pravada, 1 (6): 32-33. Available at https://polity.lk/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Giraya-the-Harsh-grip.pdf

De Costa, Nelani. (2020). “Queering Queer Representation in the Contemporary Sri Lankan English Novel.” In Selvy Thiruchandran (Ed.). Bound by Culture: Essays on Cultural Production Signifying Gender (28-43). New Delhi: Women’s Education and Research Centre.

De Costa, Merinnage Nelani. (2022). “Teaching and Learning of Queer Representation in Sri Lankan English Fiction: A Reception Study within Higher Education Institutions of Sri Lanka.” Education Research International. Available at https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3699260

Devasurendra, Tharindi. (2020). “The Heteronormative Bias in Sri Lankan Media and an Inclusive Way Forward.” Youthadvocacynetworksl (14 December). . Available at https://youthadvocacynetworksl.wordpress.com/2020/12/14/the-heteronormative-bias-in-sri-lankan-media-and-an-inclusive-way-forward/.

EQUAL GROUND. (2021). Mapping LGBTIQ Identities in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka: EQUAL GROUND. Available at https://www.equal-ground.org/wp-content/uploads/Report_EG-edited.pdf.

Ibrahim, Zainab, and Jayanthi Kuru-Utumpala. (2016). “Not just a man in a Sari: Queer Politics in Ranjan Ramanayake’s ‘Maya’.” LST Review, 28 (341): 52-56.

Illanperuma, Shiran. (2016). “Frangipani: the quiet film about Queers in Sri Lanka kicks up a storm.” Engage! (4 March). Available at https://engagedharma.net/2016/03/04/frangipani-the-quiet-film-about-queers-in-sri-lanka-kicks-up-a-storm/

Jayantha, Donald. (2016). Maya. Real Image Creations.

Selvadurai, Shyam. (1997). Funny boy: a novel. San Diego, California: Harcourt Brace.

Weerasekara, Samanthi. (2025). “Sisu samalingika sabandhathā vædi velā.” Sunday Divaina (26 January): 1-2.

Thomson, Katelyn. (2021). “An Analysis of LGBTQ+ Representation in Television and Film”. Bridges: An Undergraduate Journal of Contemporary Connections, 5 (1). Available at https://scholars.wlu.ca/bridges_contemporary_connections/vol5/iss1/7/

Prescilla, Dharini, Michael Mendis, and Pasan Jayasinghe. (2021). One Country, Many Arbitrary Laws: Rethinking Laws and Policies That Leave LGBTIQ+ Sri Lankans Behind. Sri Lanka: Westminster Foundation for Democracy. Available at https://www.wfd.org/what-we-do/resources/rethinking-laws-and-policies-leave-lgbtiq-sri-lankans-behind.

Wijenaike, Punyakante. (1971). Giraya. Colombo: Lake House Investments.

Wijewardene, Shermal, and Nehama Jayewardene. (2019). “Law and LGBTIQ people in Sri Lanka: Developments and narrative possibilities.” Australian Journal of Asian Law, 20 (1): 135-150.

Notes

[1] The term queer is used as a shorthand to encompass a range of sexual orientations and gender identities

[2] See: https://mothersmovementlk.com/creating-a-morally-civilized-society/

[3] Lajja-baya is a concept that explains the social conditioning that makes people scared of facing public disapproval or ridicule for transgressing accepted social norms and values.

[4] Representations of social and historical trauma that can disrupt existing frames of reference and provoke emotional and cognitive discomfort.

[5] “…the overloading of negatively codified social differences and symbolic excess onto figures and relationships that surround LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) characters (Cavalcante 2015).

[6] The term AFAB, i.e., Assigned Female at Birth is used to refer to transgender persons who were thought to be female based on their physical body at birth. This is used as an alternative to the old term FTM (Female to Male).

You May Also Like…

Obeyesekere the Dreamer: Visionary Journeys in Anthropology

Anushka Kahandagamage

I remember vividly one pattern in my youthful dreams repeated time and again, without too much variation, that of...

Gananath Obeyesekere: The Anthropologist and the Historian

John D. Rogers

I first met Gananath at the Annual Conference of the Association for Asian Studies in Washington DC in March 1984,...

The Creation of the Hunter. The Vädda Presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A Re-Examination. Gananath Obeyesekere. Colombo: Sailfish, 2022.

R. S. Perinbanayagam

Robert Siddharthan Perinbanayagam died on 5 November 2025 in New York City where he lived most of his life. Born in...