Decoding the Indian Elections: Class, Caste, and Social Exclusion

Roshni Kapur

Introduction

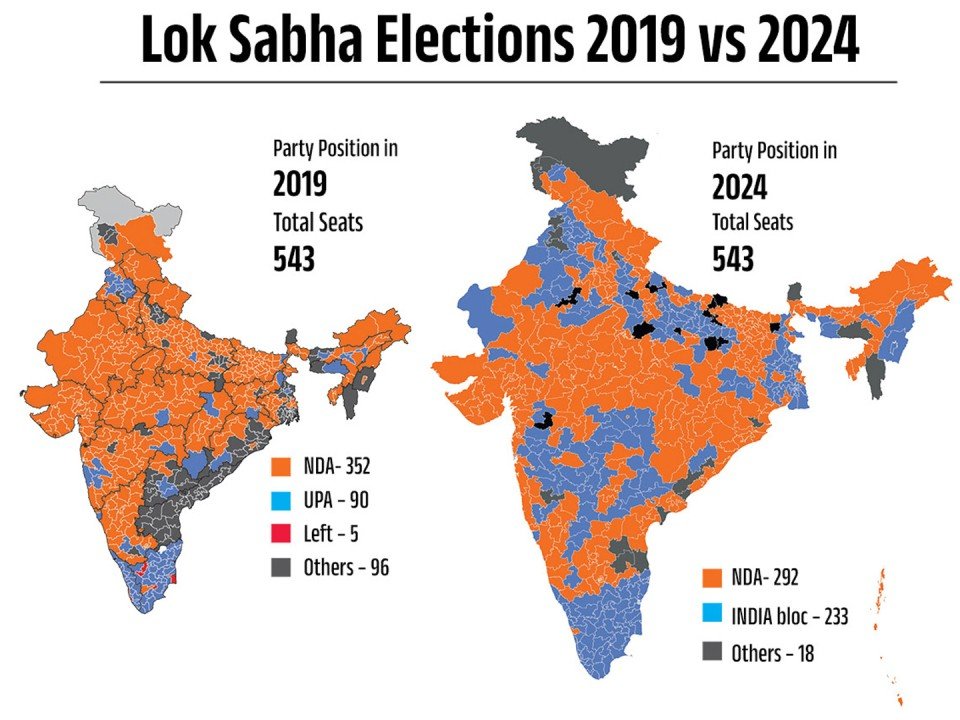

A variety of opinions and commentaries explaining the Indian ruling party’s average performance in the general election between April 19 and June 1, 2024 have been articulated in both Indian and international media. The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) electoral setback of losing its majority for the first time since 2014 suggests that its honeymoon period has finally ended. The election outcome largely came as a surprise given that almost all exit polls inaccurately predicted that the BJP and its allies would secure over 350 seats in the Lok Sabha (Lower House of the Parliament). However, analysts who conducted pre-election research on the ground were aware of anti-incumbent sentiment and disappointment with the regime’s policies.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s governance style has varied during the previous two terms. While the BJP rode on an anti-corruption wave in 2014 and focused on issues of good governance, economic growth and infrastructure development in the first tenure, there was a visible shift to national security and ethno-religious nationalism in the following term. The ruling party hoped that the opening of the Ram temple in January 2024 would play in its favour but ground evidence indicated that the inauguration was not a decisive factor for the electorate in that constituency in this poll.

While it is evident that bread and butter issues – such as unemployment, inflation, public infrastructure, and opportunities for the youth – that affect the public on a daily basis have influenced the electoral outcome, it is difficult to assess whether they have negated the State’s majoritarian and communal agenda. This point was raised by researcher Yamini Aiyar during an interview on Foreign Policy on whether voters have rejected the government’s prejudice, divisive narratives, and polarisation. Local considerations such as caste and class divides were key issues at this election, including the government’s intention to amend the Constitution if it received sufficient seats.

Mainstreaming Hindu Nationalism

The Indian government took advantage of its political grace period (honeymoon effect) during the second term when its political capital was high to implement bold reforms and further consolidate support from its core constituencies. This period witnessed less criticism of the political establishment; and high political capital and public support for its policies. State institutions also extended their goodwill to the regime. The ruling party’s communal and majoritarian activities in the last five years appear to have struck a chord with the middle class, including the Indian diaspora. Posts and videos praising controversial events such as ending the special status of Jammu and Kashmir in August 2019, and the consecration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya were commonly circulated on social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. The revocation of Article 370 in the Constitution was paraded as the return of a previously ‘suspended’ territory to the union of India and strengthened the claim for Kashmir’s full integration into the country under the BJP’s new nation-building project of changing secular India into a Hindu Rashtra (land).

A common language has been established through the State’s narrative augmented by mainstream media and easily accessible clips circulating on social media. Indian society is not exposed to these tropes without absorbing and internalising them. This type of rhetoric does not simply come and go; it changes attitudes. It is no longer frowned upon when racist remarks such as “Muslims should be taught a lesson” or “Muslims are taking over our country” are publicly made; sentiments that are now normalised in Hindu social circles in India and abroad.

Glaring Class and Caste Divisions

There was no explicit emotive, national security, or economic issue, and instead local considerations including caste equations, incumbency, and party dynamics, were more influential than national factors in voters choices. This election demonstrated that caste and class issues have returned to the centre of Indian politics and trumped other factors. The political opposition that came together under the banner of the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (I.N.D.I.A.) was coherent in its messaging by criticising the ruling party on issues of inequality, social injustice, the state of the economy, growing authoritarianism, and majoritarianism.

The government’s attempts to rewrite history and change the Constitution prompted the opposition to mount the ‘Save Constitution, Protect Democracy’ campaign that drew the likes of Backward Castes, Dalits, and other historically marginalised groups. It also promised to safeguard the Constitution which guarantees reservation to historically disadvantaged groups; and conduct a caste census to demonstrate the scale of wealth concentration in the country. One of the key parties of the opposition alliance, the Samajwadi Party (SP), that has historically promoted the interests of the Other Backward Class (OBC), managed to forge a broader caste alliance this election to appeal to marginalised caste communities.

There were legitimate concerns that a larger majority for the BJP would enable the party to remove certain reservations from the Constitution. The ‘merit versus reservation’ debate has emerged in social and institutional discourses in recent years. While proponents of the former argue that everyone, regardless of their background, should contest on an equal footing, the continuation of certain provisions for historically marginalised communities is imperative to help them compete on various fronts. Researcher Gilles Verniers has argued that the BJP continues to favour its traditional vote base of upper caste Hindus despite claims of inclusivity and looking beyond caste. The BJP has invoked the term ‘Sanatani’ to describe all Hindus, whereas it entails only Brahminical and Vedic traditions within Hinduism, excluding Dalit traditions and practices.

The BJP’s Hindutva agenda is complex and seeks to reinforce the dominance of upper caste Hindus and their practices while depending on political support from the lower caste majority to secure an electoral victory. Modi tried to reconcile this contradiction by providing welfare initiatives such as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) and other housing programmes; and vilifying the secular opposition for allegedly favouring Muslims at the expense of the welfare of low-caste Hindus. The government said that four new groups of recipients of welfare initiatives—the poor, the youth, farmers, and women—have replaced the traditional forms of caste segregation, which was picked up by the opposition to criticise the ruling party for ignoring the welfare of Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and OBCs. The opposition’s promise to carry out a caste survey and provide reservations to those who are not beneficiaries of development may have appealed to certain groups. Post-election analysis has suggested that while historically oppressed caste communities switched their vote to the I.N.D.I.A. coalition, upper castes continued to support the BJP.

The government’s welfare initiatives were considered meagre amid the economic distress of high inflation, high unemployment, and stagnant salaries. The small loans, cash transfers, food rations and subsidies complementary to the ration programme, as part of the government’s welfare agenda of providing food to 800 million people were seen as short-term relief, instead of long-term investments in the education and health sectors that are crucial to social transformation. Despite the government’s claim to provide welfare to vulnerable communities and lift masses out of poverty, inequality has increased greatly in the last 10 years. A recent study titled Economic Inequality in India: The ‘Billionaire Raj’ argues that India is more unequal now than during the British Colonial Raj: stating that “By 2022-23, top 1% income and wealth shares (22.6% and 40.1%) are at their highest historical levels and India’s top 1% income share is among the very highest in the world, higher than even South Africa, Brazil and US”.

The government’s ruthlessness in demolishing homes and slums in preparation for high profile domestic and international events demonstrates its disregard for communities affected by these activities. Several demolition drives have taken place under the Modi government, including those in preparation for the G20 summit, in attempts to enhance the aesthetics of Indian cities, without considering the adverse impact of these actions on vulnerable groups. The government conveniently used the ‘squatter’ label to evict these communities even though they have lived in these sites for a long time and have built communities around it. While many Indians were rejoicing the opening of the Ram temple they chose to ignore the dark reality of the dispossession of many residents to transform Ayodhya. Sections of the public had accepted the State’s development agenda of re-engineering cities as an inevitable action to attract foreign investment and bring economic growth even though it may result in the deprivation of fundamental rights.

The growing inequality can be contextualised in the wider realm of crony capitalism and patronage politics where wealth and power concentrate in the hands of a few powerful and influential conglomerates. Although Indian businessman Gautam Adani has enjoyed State patronage across party lines, he has benefited the most under the current government. Modi altered the rules that prevented Adani from bidding for a deal to manage six airports shortly before the start of his second term in 2019, despite objection by the Department of Economic Affairs under the Minister of Finance. Adani outbid other companies and took over the airports; and in return he acquired a big stake in NDTV, a media outlet perceived as independent of the government. The move was seen as part of a wider strategy to expand control of the mass media, to feature positive stories about the government, and downplay news that would cast the regime in a negative light.

The Indian media has been extremely selective and biased in its reporting over the past decade. Disproportionate coverage has been given to high profile and pompous events such as India’s hosting of the G20 and the pre-wedding and wedding celebrations of Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant; over major crises such as the violence that unfolded in Manipur in 2023. The widening inequality coupled with favouritism given to big conglomerates casts scepticism on the State’s narrative of being a guardian for the underprivileged and poor. The pliant media’s constant projection of Modi as a humble, modest, and non-elitist leader, in contrast to the nepotistic and corrupt Congress, particularly its leaders, appears to be a public relations exercise.

Conclusion

Following the completion of two terms and enforcing several controversial decisions, it is evident that Modi’s style of governance is non-consultative, undemocratic, and authoritarian.

There is also short-sightedness to prepare for negative implications for their policy decisions in the medium-to-long term. His administration has unilaterally enacted controversial legislation without conducting proper consultations with relevant actors and following parliamentary procedure. The demonetisation policy, that invalidated Rs500 and Rs1000 currency notes overnight, became the government’s blueprint of taking bold and unilateral decisions. The passing of three agricultural laws without any parliamentary debate – since repealed following mass protests – further exhibited the establishment’s undemocratic posturing.

It is evident that caste and class divides have widened in the last decade despite the government’s rhetoric that it has provided welfare programmes to uplift the poor, and undertaken efforts to include historically oppressed castes under the Hindutva banner.

Roshni Kapur is a PhD student at the University of Ghent focusing on caste and land conflicts in Sri Lanka. She specialises in identity politics, conflict resolution, transitional justice, post-war reconciliation, domestic and party politics of South Asia. She is an editor of Sustainable Energy Transition in South Asia: Challenges and Opportunities (2019). Dr Rajni Gamage and Mr Anand Sreekumar are thanked for comments on the draft version.

Image Source:https://bit.ly/3X1b7Lx