Budget 2025: Playing A Bad Hand

B. Skanthakumar

- Introduction

‘Budget 2025’ – delivered before parliament on 17 February by President Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) in his capacity as Minister of Finance and passed on 21 March – is the first concretisation of the economic agenda of the new government in national office. Prima facie, it is a statement of the revenue and expenditure plans in the year ahead. What, how much, and for what end, are public funds allocated. How much, from where, and importantly from whom, are those resources to be raised. Its significance is however, much wider.

For those throttled in the continuing economic crisis, there is hope of slight relief from, or at least assistance in adapting to, its pain. For those energised by the class project that shapes the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) 17th programme with Sri Lanka, there is vigilance on whether the new regime is within its parameters, that is monetarist conditionalities. For champions and critics of the National People’s Power (NPP) alike, the interest is whether the Budget Speech validates their stance on the political character and socio-economic orientation of the regime.

Hence the Budget also takes on political significance. It gauges the government’s grasp of the challenges it has inherited from its predecessors but must now confront; and its proposed plan of action. What kind of society do our rulers envision for our people? What is their itinerary; and with what implications? Which social groups will be its winners and losers?

Before delving into the numbers, something striking in AKD’s speech are his critical references to income inequality and inequitable growth. By no means radical statements in and of themselves, they are nevertheless strange to our ears from those in office in an epoch of market fundamentalism and right-wing authoritarianism.

The top 20% of households account for 47% of national household income, reported AKD citing the 2019 Household Income and Expenditure Survey, to drive home that the economic policies of his predecessors have fattened the favoured few.

This data is pre-pandemic and pre-crisis. During the pandemic, analysis by the UNDP (2023: 19) indicates that income and wealth inequalities have since widened at an accelerating pace. The richest 10% of the population commanded an obscene 40% of the share of national income and a whopping 65% share of national wealth. The bottom 50% of the population subsisted on only 17% share of national income and 3.8% of the wealth share. This is an explosive situation with no good outcomes for anyone, but threatening social and political ideologies and their menacing standard-bearers in civil and political society.

Further, AKD in his opening remarks said that economic growth should be inclusive, which according to him means that greater economic opportunities should be accessible to all citizens, and where all “strata of society” equitably receive its benefits.

Growth for the sake of growth has little value to society unless it is a means to uplifting the lives of all members of society. For several decades, economic activity and economic benefits have been concentrated amongst the few … what is needed going forward is for a greater democratisation of the economy, where economic opportunity is more fairly distributed. Mass struggles and last year’s election saw people asserting their political rights. What is necessary is for economic rights to be similarly asserted (Dissanayake 2025: 4-5).

These are fine and important words. Unfortunately they are not matched by the proposals in this budget. It is unfathomable how economic democratisation is to be realised without a redistributive thrust that begins reversing income and wealth inequalities through progressive taxation, curbs on excess profits, and expropriation of ill-gotten assets. There is not even a leash on the big capitalists whose market and political power harm producers and consumers, as well as the small and medium-scale ‘entrepreneurs’ exalted by this government. There is no rendezvous between progressive political goals; and the regressive social and economic practices of the international financial institutions framing the Budget.

Section one has outlined what a budget speech is explicitly, and implicitly, about. It highlighted the president’s opening salvo on inclusive economic growth. Section two picks up on four distinct motifs in this speech – on children; on digitalisation; on Malaiyaha Tamils; and on the Northern Province. Section three steps back to take in the big picture on expenditure and revenue, with particular attention to the unresolved problem of sovereign debt. Section four compares the eight largest allocations for expenditure by ministry heads between this year and 2024, with a focus on defence and social welfare. Section five offers a brief review of, and raises disquiet over, the government’s revenue targets and proposals. Section six concludes with reflection on the government’s political choices in its management of the economy.

- Four motifs

There are four motifs that stood out to this reader in the Budget Speech. They are (in alphabetical sequence): on children; on digitalisation; on Malaiyaha Tamils; and on the Northern Province.

2.1. Children

In an unprecedented series of initiatives, under-resourced though they are along with everything else of importance, is a focus on two groups of forgotten children in particular: those with neurodevelopmental disorders; and those who are in state care. This must surely owe to the social and professional backgrounds of the women in the NPP’s parliamentary group. A case in point: it is no coincidence that before taking to party politics the prime minister investigated child protection within the Department of Probation and Child Care Services for her doctoral studies; and that before joining academia, Harini Amarasuriya was a practitioner and researcher in community-based psychosocial and mental health wellbeing.

A five-year national programme for children with neurodevelopmental disorders was announced, beginning with a specialist treatment centre at Lady Ridgeway Children’s Hospital in Colombo (200 million LKR). A preschool for children with autism is to be developed as a model for rollout elsewhere in the future (250 million LKR). Children’s orphanages and remand centres operated by the state are to be upgraded and staffing improved (500 million LKR). Child-friendly transport to and from court will be provided for young people in juvenile custody and care. A monthly cash allowance of 5,000 LKR will be granted to children in care and in legal custody. These children will also be enrolled in good quality national and provincial schools to improve their life chances. Young people in rehabilitation centres will be skilled and certified by the National Vocational Qualification system to improve their labour market opportunities. Those formerly in care and without family support, once of marriageable age. will be eligible for a housing construction grant (1 million LKR) to start them off in life. Mental health wellbeing (particularly suicide prevention) awareness and counselling services for teenagers are to be expanded (250 million LKR).

2.2. Digitalisation

If there is one theme drilled in this speech, it is digitalisation, whose root word figures 37 times across it. This is the NPP’s silver bullet for economic transformation, within the public investment restrictions from the IMF’s ‘fiscal consolidation’ programme. Digitalisation will rid the public sector of corruption in procurement and provision of public goods; increase efficiency gains; and enhance ease of access to services, is the message. Digital tools and platforms are expected to eliminate corruption and waste, and foster transparency. For instance in the import, manufacture, pricing, and sale of medicinal drugs, where health ministers, their cronies, and senior officials have amassed fortunes.

Tax administration will become more efficient, and revenue collection enhanced, through digitalisation of economic transactions. The biometric identification of the population in a digital identifier, initiated in the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration, is one short-term priority. A digital payment infrastructure, building on the recently launched GovPay, for transactions between state agencies, businesses, and citizens is another, in the “shift away from a cash-based economy”. Sri Lanka can aspire to a digital economy valued at 15 billion USD by 2030, where revenue from export of IT services reaches 5 billion USD (from around 1.5 billion USD last year), believes the president.

There is no discussion of how digital divides across class, gender, age, ethnicity, et tutti quanti, are to be bridged so as not to create new inequalities while reinforcing old exclusions. Neither is there due recognition of issues of concern integral to digital capitalism. The expansion of power of tech companies and their owners, for whom public procurement and government services are the next frontier for capitalist accumulation, and the commodification of the personal data of citizens, have serious consequences for democracy and freedom. In a speech reminiscent of Harold Wilson’s invocation of the ‘white heat of the technological revolution’, there is no mention of the freedoms of workers, including those super-exploited and dispossessed of their rights on digital platforms.

2.3. Malaiyaha Tamils

In a historic gesture, the president used the term Malaiyaha/m (‘hill country’) to identify those too long labelled in government records and by the national census as ‘Indian Tamils’. They are “a part of the Sri Lankan nation,” he said; and their livelihoods must be improved “to have a dignified life”. Estate housing and infrastructure, a major blight for those who live on British colonial-era tea and rubber plantations, is allocated 4.267 billion LKR. It is unclear whether these will be independent houses on 10 perches of land to enable home gardening as the community desires; or high-rises as has been absurdly suggested recently. There is silence on land rights for the community; as this government, similar to its predecessors, thinks it adverse to plantation production. Housing construction funded by the central government is painfully slow. Between 2023 and 2025, the target was only 387 units.

The woeful health facilities where they exist on estates are to be strengthened through “public-private partnership” with the regional plantation companies that are their nominal providers. The government will supply human resources, equipment, and pharmaceuticals, is the pledge. There is no allocation specified. Nor is there reference to a timetable for the absorption and integration of all estate hospitals and medical facilities in the national public health system.

Vocational training and livelihood development of youth is allocated 2.45 billion LKR. The upgrading of school classrooms with smart boards is allocated 866 million LKR. The immediate and urgent needs for accessible and quality education in the Malaiyaham are more prosaic: teachers for mathematics, science, information technology, and English; travel and transport for students and teachers; sanitation and water facilities; nutritional interventions for mothers and infants; and so on.

The government “will intervene” with employers to increase the daily wage of estate workers to 1,700 LKR. This was the rate fixed by the tripartite Wages Board in August 2024 when Ranil Wickremesinghe’s regime was eyeing estate sector votes. It is substantially less than the 2,000 LKR market wage for daily off-estate rural labour. What confidence can workers have in this promise when the private sector companies who employ them have frustrated the legal minimum for years and there is inaction by the state?

2.4. Northern Province

Development projects in the region most devastated by decades of war, displacement, and socio-economic dislocation receive emphasis. The rehabilitation of the road network and reconstruction of the emblematic Vadduvakal bridge is allocated 6 billion LKR. The resettlement of internally displaced persons and refugee returns, including for housing, is allocated 1.5 billion LKR. Coconut seedlings are to be planted with an investment of 500 million LKR across 16,000 acres between Jaffna, Mannar, and Mullaitivu to boost local production and incomes. The Jaffna Public Library receives half as much (100 million LKR) as all other public libraries combined (200 million LKR). An industrial zone to manufacture chemical products will be established in Paranthan; and an industrial park each in Mankulam and Kankesanthurai. This could be seen as rewarding the North for the unexpected mandate for the NPP in the parliamentary election; or symbolic of the government’s efforts to build peace with Northern Tamils through economic progress, with no political or constitutional package – beyond the reactivation of the provincial council system through elections before the end of this year – on offer.

- Headline estimates and debt servicing

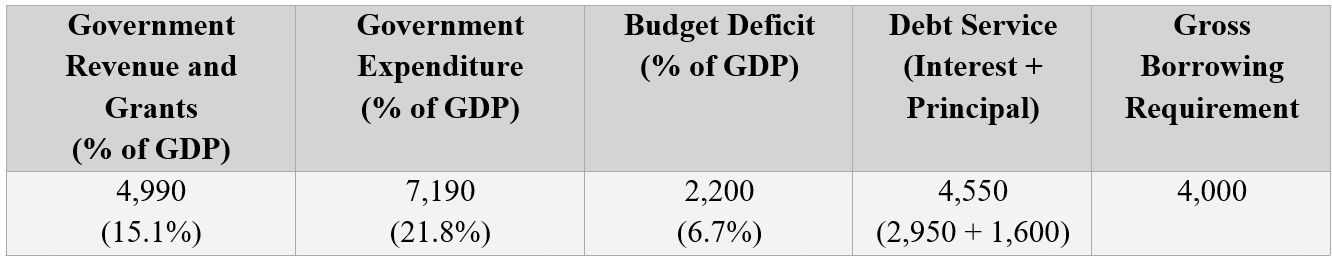

Let us begin with a quick scan of the headline numbers for 2025. Below are the government’s estimates in billions of rupees for projected revenue and grants; for expenditure on maintaining the state and societal programmes; the gap between the two; the cost of servicing the country’s domestic and foreign debt; and the ceiling for what it needs to borrow to finance the shortfall in meeting those repayments.

Exhibit I: Headline estimates (in billions of LKR)

Source: Extracted from Budget Speech 2025, Annexure I and II, pp. 58 & 59

As usual, there is a chasm between incomings and outgoings, amounting to a deficit of 2,200 billion LKR (2.2 trillion rupees). However, in line with the IMF agreement, this difference as a proportion of GDP is in marginal decline since 2023. Also, in conformity with IMF conditionalities, Sri Lanka’s ceiling for borrowing to plug that gap is capped at 4,000 billion LKR (4 trillion rupees).

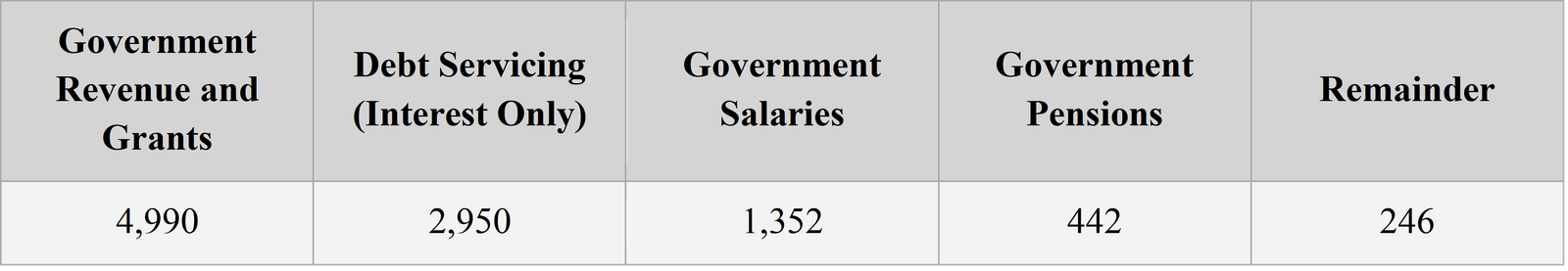

The grimness of the government’s finances in Sri Lanka’s crippling indebtedness were laid bare by the president in his speech on the third reading of the Budget on 21 March, closing the parliamentary debate and before the vote. Once deductions are made from government revenue and grants for interest payments alone on debt, and government salaries and pensions, what remains for public investment is paltry.

Exhibit II: Government revenue in relation to selected expenditure (in billions of LKR)

Source: “President Expresses Confidence on the Country’s Prosperous Future”, 22 March 2025, President’s Media Division, https://pmd.gov.lk/news/president-expresses-confidence-on-the-countrys-prosperous-future/

Sri Lanka is a poor country economy without the double-edged sword of fossil fuels, agricultural cash crops, and minerals, that enabled Latin American ‘pink tide’ governments to resource expanded social protection, infrastructure and industrial development, from record export revenues. Its main manufactured export of readymade garments is reliant on preferential tariff access and consumer demand in the United States and the European Union. Its foreign exchange reserves assumes uninterrupted and rising flows of migrant remittances and tourism receipts. Its essential imports of fertiliser, fuel, food, and pharmaceuticals must be financed from overseas.

Shocks, whether exogenous or endogenous, such as a global public health emergency, volatility in commodity prices, extreme weather events, disruptions in logistical supply chains, and so much more that is unforeseen and unavoidable, that exhaust foreign exchange reserves; coupled with downgraded sovereign risk ratings of CC by December 2021 that cut off access to money market borrowings, render the rapidly growing mountain of debt unserviceable and therefore unsustainable. This is the now familiar story of Sri Lanka’s debt default.

The Government of Sri Lanka suspended payment dues on international sovereign bonds – amounting to 18.56 billion USD including interest arrears as of July 2024 (Yukthi, IPE & Debt Justice 2024); and 48% of external debt stock as of April 2022. It also stopped servicing bilateral debt of around 10.6 billion USD at the same time. Nevertheless, it continued servicing multilateral debt (including to the IMF), even while in default status. Last year, it restructured borrowings from official creditors, beginning repayments on accumulated interest arrears from this year onwards.

What is the outcome of Ranil Wickremesinghe’s deals? This year alone – that is before Sri Lanka begins repaying the largest single chunk of external debt, to bondholders, from 2027 onwards – the debt servicing burden to domestic and foreign creditors (4,550 billion LKR) is almost equivalent to total government revenue and grants (4,990 billion LKR). As Dhanusha Gihan Pathirana of the Institute of Political Economy-Sri Lanka warned last year, “The backdating of restructuring agreements to 2024 and the conversion of past due interest into a plain vanilla bond of $ 1.7 billion maturing from 2024 to 2027 have exacerbated the debt burden …” (2024c).

Instead of challenging the agreements made with ISB holders and official creditors, by a predecessor without a public mandate who wielded state power derived from a rotten parliamentary majority surrendered by the Rajapaksas, the new government chose to stick by these bad deals (Pathirana 2024a &b).

Consequently, there is no fiscal space for the public spending needed to protect the poor and other sectors, whose living standards are pummelled by the socio-economic crisis that began during the COVID19 pandemic. Debt servicing swallows many times more the allocations for social protection, employment creation, affordable credit, livelihood and income generation, and access to adequate food, health, and education. Neither does it afford the capital resources to reorient an economy subordinated since centuries of colonialism in the capitalist world market, towards domestic production and economic sovereignty, as upheld by the NPP manifesto which is now the policy framework of this government.

International debt justice campaigner Eric Toussaint (2025) observes, “… a historic opportunity is being lost due to the authorities’ insistence that they will ensure continuity of debt obligations.”

He argues that,

… under international law, a change of government or of regime opens the possibility for the new government to renounce earlier debt commitments if the debt being claimed against the country is odious in nature.

In this case the NPP could definitely say that there has been a change of regime, since the people clearly demanded a change of regime through its massive vote for the NPP and its candidates, most of whom are newcomers. The situation is indeed a regime change, because the people refused to re-elect members of Parliament who in some cases had held their seats for decades. The population elected new faces out of a desire for fundamental change. Therefore from the point of view of the majority of the population, there has been a change of regime. The NPP alliance called for fundamental change, but according to the government that fundamental change did not apply to commitments to creditors. Yet if those commitments are not called into question, there has been no authentic change.

- Ministerial allocations

Where ministry allocations are glanced at, there appear to be many similarities in the budgets of Ranil Wickremesinghe in 2024 and Anura Kumara Dissanayake in 2025. This is because both budgets are bound by the “guardrails” of the IMF’s 2023 programme:

- Primary budget surplus (that is, government revenue over expenditure) of 2.3% of gross domestic product from 2025 onwards (from a deficit of 3.7% of GDP in 2022);

- Reduction in the government’s borrowing requirement (or gross financing needs) to 13% of gross domestic product after 2027 (from 34.1% of GDP in 2022);

- Reduction in the ratio of public debt to gross domestic product to 95% by 2032 (from 126.3% of GDP in 2022).

These targets have since been codified in the ordinary law of the land by Wickremesinghe through the 2024 Economic Transformation Act. The NPP challenged the bill before the Supreme Court but did not vote against it, when it came before parliament. Indications are that the NPP will not repeal the Act but only amend the part concerning abolition of the Board of Investment and creation of new investment promotion bodies.

The IMF programme is a cage. “Instead of empowering the Government to upgrade the hardware and strengthen the structural power of the economy – boost industries, restore developmental infrastructure, and elevate skills and technology, the IMF program limits planning and action to the bare minimum and vulnerable sectors like tourism”, observes Amali Wedagedera (2025) of the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies.

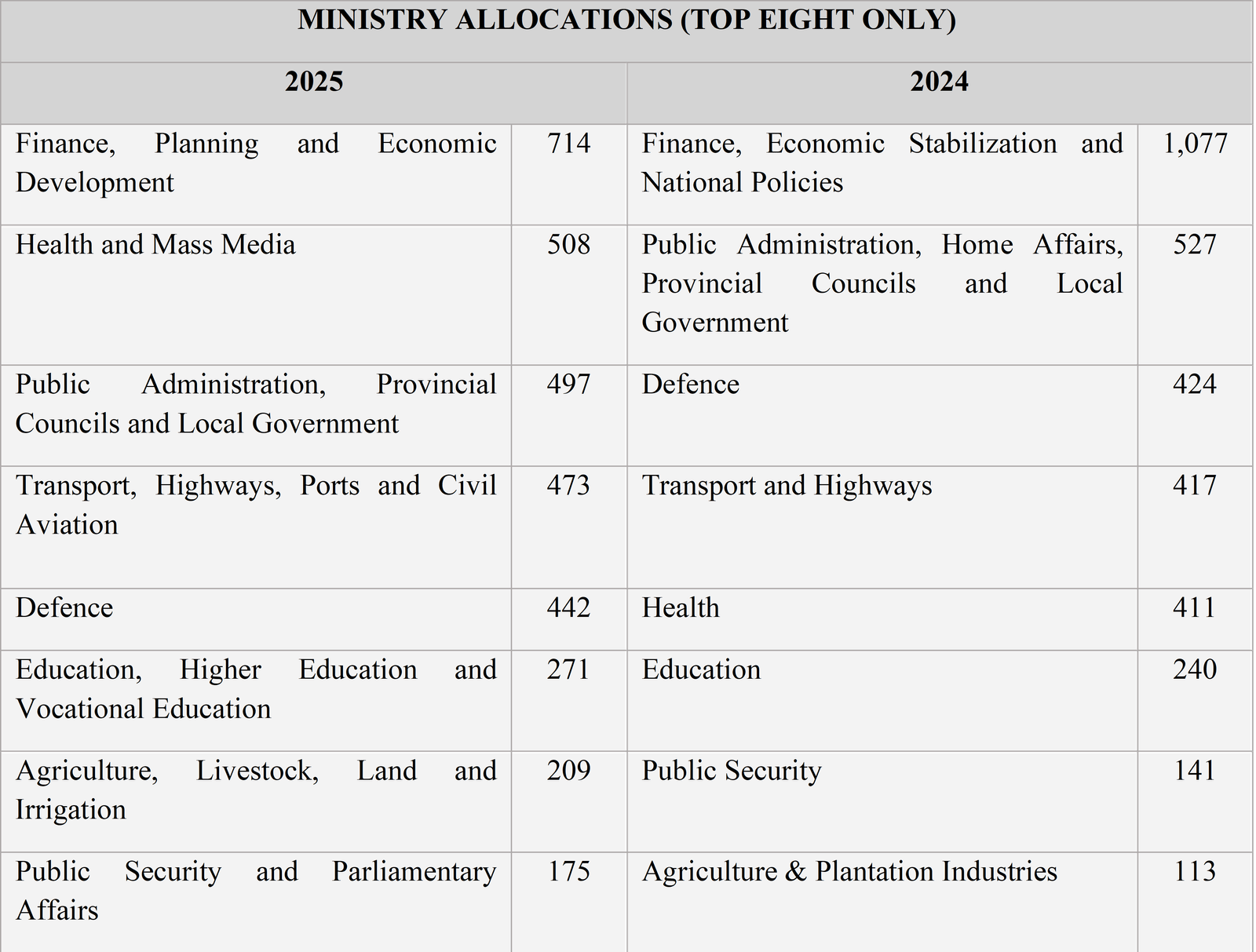

Exhibit III: Ministry allocations (in billions of LKR)

Source: PublicFinance.lk, 07 January 2025, https://publicfinance.lk/en/topics/appropriation-bill-2025-which-ministries-got-the-highest-allocations-1736509323

4.1. Defence spending

Glaringly, defence spending continues its upwards trend, as it has consistently over the nearly sixteen years since the end of the war. When taken in combination with public security (specifically the police service) it becomes the second largest head of expenditure both last year and this. The Defence Ministry head includes subjects such as disaster prevention and management; the Meteorology Department; and the Sir John Kotelawala Defence University. Let us look more closely at the allocations for the repressive state apparatus contained only in that head.

Exhibit IV: Armed forces allocations (in billions of LKR)

Source: Ministry of Finance, Budget Estimates 2025 (Draft), pp. 68-71, https://www.treasury.gov.lk/web/2025-draft-budget-estimates

In the three branches of the armed forces, the gradient of increase in allocations is slight rather than sharp, apart from the navy. Even at current levels of infrastructure and cadre, there will be higher recurrent costs year-on-year. When it comes to hardware purchases: the Navy is picking up a decommissioned cutter from the US Coast Guard; and the Air Force is acquiring two Chinese-built Y-12-IV light passenger and cargo transport. There appears to be no spending spree on armaments.

On the other hand, the allocation for supply of food and uniforms has ballooned from 70.7 billion LKR (in 2023) to 101 billion LKR (in 2024) and now 135 billion LKR (in 2025), which according to Nishan de Mel of Verité Research suggests either the disguise of allowances as procurement-related costs instead of as salaries and emoluments as they should be, or “a case of procurement corruption” (Rizkiya 2025).

Further, the considerable increase in funding for the intelligence service ought to sound an alarm. It is better known for preying on rather than protecting citizens; and widely alleged to have had a hand in the 2019 Easter Sunday terrorist attacks and their cover-up.

The president, at the committee stage debate on the defence head on 28 February, reiterated that by 2030, the army will be reduced to 100,000; the navy to 40,000 and the air force to 18,000 (Daily FT 2025). This ‘right-sizing’ as we are told to call it, was first announced by the previous government. There is no verified data on the current number of personnel, which is believed to have been in excess of 300,000 at the end of the war in May 2009.

However, it is accepted that Sri Lanka, which by size of population is 60th in the world, ranks 17th when it comes to the size of its military. This organ of the state, out of bounds in the right-wing discourse on reduction of the public sector workforce, as of 2023 gobbled 48% of the payroll (PublicFinance.lk 2023).

There would be enormous political, economic, and social costs, destabilising any government that tried to slash the size of an overdeveloped military overnight. However, there is no indication from the Budget Speech, nor the draft Budget Estimates, of a phased programme for the demobilisation and reintegration of military personnel in the civilian population. It seems as if natural attrition through retirement and resignation, and a freeze on recruitment to the army, is the course of action. How can this be satisfactory? In a sluggish economy where there are few good quality jobs with decent incomes, what will over 100,000 men of early middle-age trained in weaponry and violence do? Already, many contract killings, including in recent weeks, are undertaken by ex-military and deserters, and sometimes even current personnel.

Of concern too is that there is no allocation in 2025, unlike last year, for the dismantling of military bases in the north and east. The demilitarisation of the Tamil-speaking majority areas, which is where much of the military are stationed, ought to be a priority. The return of lands where people once lived, farmed, and had access to the sea, would be more meaningful than any number of state-sponsored celebrations of communal harmony and liberal multiculturalism. The reduction of military bases, checkpoints, and armed uniformed men – their removal being distant – are steps towards release from occupation. With no prospect of truth and justice for the disappeared and the victims of crimes against humanity, at least the living deserve dignity and respect.

4.2. Social Welfare and Relief

The largest ministerial head of allocation is Finance, Planning and Economic Development. Its expenditure includes the Aswesuma poverty alleviation programme and relief schemes for specific vulnerable groups. From across the Budget Speech, below is an inventory of the government’s boost to social welfare schemes, and initiatives for relief from cost-of-living increases transmitted to the people through market-pricing of energy and devaluation of the rupee over the course of the crisis.

Exhibit V: Social welfare and relief (in thousands of LKR)

Source: Compiled from the Budget Speech 2025

Any enhancement of allocations for the marginalised and the vulnerable, so often the victims of hate and heartlessness in rich and poor countries alike, is laudable. However, the effect of these increases and interventions is blunted by their scale in relation to the immensity of the crisis.

One in four people are officially poor in Sri Lanka. The World Bank (2024) estimates the poverty rate at 23.4%; and food insecurity at around the same level, with 23.7% of households being “food insecure” and 26% of households “consuming an inadequate diet”.

Presently the official national poverty line is 16,334 LKR per person per month (Department of Census and Statistics 2025). In other words, this is the estimated minimum expenditure per person for basic needs. However, it is based on the 2012/13 Household Income and Expenditure Survey that is woefully outdated. Compare this with average household monthly expenditure back in 2019 (the most recent available data), which was 63,130 LKR (Department of Census and Statistics 2022: 18).

Remember this is pre-pandemic, pre-crisis, pre-inflation (of food items) hitting 94.9% in September 2022, and pre-depreciation of the rupee by at least 40%. It should be recalled that private sector trade unions in January called for the minimum monthly wage for workers to be raised to 31,000 LKR excluding the budgetary relief allowance of 3,500 LKR, as their salaries in the lower grades have stagnated in comparison to the public sector.

In this context, as Niyanthini Kadirgamar (2025) of the Feminist Collective for Economic Justice comments, “Disappointingly, the 2025 Budget fails to make social protection for the most precarious families a budgetary priority. The amount allocated for cash transfers to low-income families under the Aswesuma program is Rs. 160.1 billion, which amounts to a meagre 0.5% of GDP”. Even when all other social assistance schemes are added up and combined with Aswesuma, total expenditure does not exceed 0.7% of GDP.

It is horrific that when millions of people are food insecure, and have been since the COVID19 pandemic, there is still no emergency programme to reinitiate the food and nutrition interventions stripped away in previous structural adjustment programmes, aside from the limited expansion of school meals. We shall reap the consequences over generations, and in the strains caused to, and within, the public education and health systems too.

- Revenue Estimates and Proposals

The government’s revenue estimates are of course based on certain assumptions (Ministry of Finance 2025: X). These include that economic growth will be between 3% and 5% in 2025; that inflation will be contained below 5%; that open unemployment will be below 5%; that the exchange rate will be stable; that the relaxation of imports of motor vehicles will yield the desired duties; that public finances will be used more prudently; that revenue administration by the Inland Revenue Department, the Department of Customs, and the Excise Department will strengthen; and that tax compliance by individuals and firms will improve.

The bulk of the revenue gains are anticipated from customs duties on imported motor vehicles (300 billion LKR). If sales are lower than anticipated owing to the high sales prices, the revenue gain will be below expectation, deepening the budget deficit. There is also imposition of VAT on digital services; corporate income tax on export of services; and tax increases on cigarettes, liquor, betting, and gaming. The capital gains tax is to be raised to 15% for individuals and partnerships; and to 30% for all other entities.

Ninety-two percent of the government’s projected revenue in 2025 is from taxation. Let us look at the trend between 2023 and 2025 of the most consequential taxes.

Exhibit VI: Selected tax revenue (in billions of LKR and rounded up)

Source: Ministry of Finance, Budget Estimates 2025 (Draft) Volume III, XXIV-XXV

The data above conveys how tax collection particularly from consumption has sharply risen. Such taxes, particularly value-added-tax (VAT) on imported goods and services disproportionately penalise the lower middle-class and the poor. Their disposable income is of course considerably lesser than the rich; and a considerably higher proportion of it is liable to indirect taxes. Conversely the tax take on income and profits that targets the upper middle-class and the rich is rising very slowly. This is true too for corporate income taxes. For instance, Nishan de Mel of Verité Research calculates that since 2017, the tobacco industry’s post-tax revenue has surged by 92%, whereas tax revenue from sale of cigarettes has only risen by 27% over the same period, “suggesting a growing imbalance that favoured corporate profits over public funds” (de Silva 2025).

Absent from this year’s Budget Speech is what the government will do on the scandal of mis-invoicing by exporters and importers, whereby around 4 billion USD a year is not repatriated as it should (Samaraweera 2024). Neither has the government disclosed whether and how it proposes to plug the leakage of revenue from tax holidays and exemptions granted to corporations. Between March 2023 and December 2024 (21 months) alone, the Finance Ministry’s own estimation is that 965.6 billion LKR has been lost to the public treasury as presented below.

Exhibit VII: Revenue from Duties Foregone (in billions of LKR)

Source: Ranasinghe, Imesh. 2025. “Rs. 965 b forgone in taxes over 21 months”, The Morning, 21 February 2025, https://www.themorning.lk/articles/1vAcIV5cJIoSzg2yFnsv

The above concessions to the rich and powerful are more generous than the government’s proposed spending on health, education, and agriculture combined in 2025.

The new government shows no inclination to depart from this longstanding class bias but rather to reinforce it. In this Budget Speech, the exemption from VAT is extended for supply of goods and services, from and to, a “business of strategic importance” as designated by the Colombo Port City Economic Commission. Among the new legislation proposed for 2025 as notified in the Budget Speech, is an Investment Promotion Act “to safeguard the rights of investors and provide a conducive environment for foreign investment”. Also announced is a Public-Private Investment Management Act “to encourage foreign and domestic private investments in collaboration with the public sector”, public-private-partnerships being “a crucial factor for the country’s rapid economic development”.

A host of revenue raising proposals that begin shifting the burden of debt servicing from the poor to the rich, have been proposed by Charith Gunawardena (2025) of the Institute of Political Economy-Sri Lanka. These include offsetting VAT exemptions on essential goods and services while increasing duties on non-essential luxury imports; carbon tax on greenhouse gas emissions; surcharges on banks and other financial institutions; minimum 15% corporate tax on multinationals; wealth tax on high-net-worth individuals, etc. There is no reason why these cannot be integrated into the next budget.

- Conclusion

The framework of the Budget is within an IMF straightjacket. Public debt management – that is, prioritising the repayment of borrowings of which a significant portion are odious or illegitimate (Ruwanpura 2025) – takes precedence over public investment in government services, in employment creation, and in social spending. Government revenue is derived from hammering the poor through indirect taxation on consumption; instead of squeezing the rich through higher direct taxes on income and wealth.

There is no break from austerity economics. The welcome albeit modest increases in social welfare transfers are compatible with – and not a break from – commodification, deregulation (including of labour rights in formalised work), marketisation, privatisation (in the guise of public-private partnerships), trade liberalisation (through free trade agreements), and the rule of foreign and domestic capital (including in agriculture as said in the Speech).

The IMF’s satisfaction with the debt restructuring deals (negotiated by the Wickremesinghe regime) and the NPP government’s commitment towards them, is confirmed in its Executive Board decision of 28 February to release the fourth tranche of 334 million USD from the Extended Fund Facility loan; delayed since late last year while awaiting confirmation of the government’s revenue and expenditure proposals for 2025.

Why are there greater continuities than discontinuities between the budget of a government led by a left party, and those of its right-wing predecessors?

Arguably the AKD administration had little time for budget preparation between the presidential and parliamentary elections of September and November last year; and the exhaustion of funds approved in December by parliament in its ‘Vote on Account’ by April this year. Neither, may it be assumed that it has the active cooperation of the state machinery in translating positions developed in opposition, into executable actions when in office. Although ministry secretaries being presidential appointees may be politically sympathetic to the new government, their support alone is insufficient. The bureaucracy is more than the sum total of hand-picked officials and NPP members newly elevated to institutional leadership.

The new government had even less by way of policy space. Ranil Wickremesinghe’s austerity pact with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in March 2023, was designed to make the poor pay for the crisis. This ruling class offensive was reinforced by a slew of legislation in 2024 – the Public Debt Management Act; the Public Financial Management Act; and the Economic Transformation Act – that translated the methodologically suspect quantitative targets and structural benchmarks of the IMF’s ideology, into statutory law undemocratically binding all successive governments.

But the NPP while in opposition, and in its election manifesto, promised it would not break the shackles clasped upon the people by its predecessor. Instead, it would “renegotiate” their tightness. Once in government though, there is nary a whisper of challenging the conditions in the IMF programme. The received wisdom across political and civil society is that a country not long ago in free fall would be foolish to jettison the parachute on loan from the guardian of the international monetary system. This apprehension has been absorbed and internalised by the electorate since the crisis peaked in 2021-22. Evidently so too by this government.

Elected by an overwhelming majority of the common people desperate for progressive change, the AKD administration opted to follow the counsel of its economic advisors representing the Treasury Department, the Central Bank, and the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce. The advice of this troika on debt restructuring was that to begin afresh would drag out resolution by months or years; add to the accumulation of interest arrears at the high rate on which loans were taken; postpone upgrading of sovereign credit ratings; and upset relations with creditors and the IMF. “Stability” and “trust”, before and above all else, is the mantra.

Evidently, the JVP/NPP leadership while in opposition was already of a similar view. Since assuming office, there is no indication it sought other advice or explored any alternatives. “This economy cannot withstand drastic shocks … [a]ny disruption would only further harm the already delicate economic system … it would be impossible for us to move the economy forward without completing the debt restructuring process”, regardless of whether it is “good or bad, advantageous or disadvantageous”, said the president at the inauguration of the new parliament on 21 November (Dissanayake 2024).

In his Budget Speech, AKD having rightly identified the underlying causes of Sri Lanka’s combined social, economic, and political crisis as being “historical and structural”, proceeded to identify its root causes as being “[c]orrupt governance, failed economic policies and irresponsible public financial management”.

Corruption, the perennial fallback in the NPP playbook, becomes a primary source of our crises rather than among its debasing symptoms; and is given equal weight with other “root causes”. Which incidentally is also why it is puzzling that this government is not auditing the debt (as proposed in its manifesto) to determine which part of it stems from grand corruption by politicians and public officials.

The hegemonic economic paradigm that promotes debt-fuelled maldevelopment, is unnamed as neoliberalism. The international structure of power forged during colonialism and backed by force, which determines what is produced and consumed and by whom; what is exported and imported and by whom; and the unequal and predatory terms of trade and relations between national economies in the world market, is unnamed as imperialism. The totalising system within which public resources are marshalled and dispensed, from whom and to whom, is unnamed as capitalism.

These categories of seeing to act upon the world are not unknown to the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna. By folding into the mentalité of the intermediate classes from whom they sprung, and who characterise the National People’s Power, they have simply chosen to evacuate them.

B. Skanthakumar is with the Social Scientists’ Association (SSA) of Sri Lanka; and the Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM).

Image source: https://bit.ly/41ZBDHN

References

Daily FT. (2025). “President AKD vows civilised Sri Lanka, professional armed forces.” (1 March): https://www.ft.lk/top-story/President-AKD-vows-civilised-Sri-Lanka-professional-armed-forces/26-773636

De Silva, Charumini. (2025). “Top economist criticises Govt,’s overestimated excise duty revenue projections.” Daily FT (22 February): https://www.ft.lk/front-page/Top-economist-criticises-Govt-s-overestimated-excise-duty-revenue-projections/44-773380

Department of Census and Statistics. (2022). Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2019 Final Report. Available at https://www.statistics.gov.lk/IncomeAndExpenditure/StaticalInformation/HouseholdIncomeandExpenditureSurvey2019FinalReport

Department of Census and Statistics. (2025). “Official poverty lines by district: January 2025”. Available at https://www.statistics.gov.lk/povertyLine/2021_Rebase#gsc.tab=0

Dissanayake, Anura Kumara. (2024). “The Full Speech Delivered by President Anura Kumara Dissanayake at the Inauguration of the First Session of the Tenth Parliament.” The Parliament of Sri Lanka (25 November). Available at https://www.parliament.lk/files/documents_news/2024/president-speech-nov-21-2024-en.pdf

Dissanayake, Anura Kumara. (2025). “79th Budget Speech – 2025”. Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (17 February). Available at https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/fd89eb07-4b9d-4f86-97d3-bdfed2025a0b

Dissanayake, Anura Kumara. (2025). “President expresses Confidence on the Country’s Prosperous Future.” President’s Media Division (22 March). Available at https://pmd.gov.lk/news/president-expresses-confidence-on-the-countrys-prosperous-future/

Gunawardena, Charith. (2025). “Progressive Taxation Policies for new era.” Daily FT (6 February): https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Progressive-taxation-policies-for-new-era/14-772736

Kadirgamar, Niyanthini. (2025). “IMF’s iron clasp, a maiden Budget and protecting the poor.” Daily FT (21 February): https://www.ft.lk/opinion/IMF-s-iron-clasp-a-maiden-Budget-and-protecting-the-poor/14-773318

Ministry of Finance. (2025). Budget Estimates 2025 (Draft) Volume III. Available at https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/80d85f8a-3d16-4dcf-af9f-01b6c78a3edc

Pathirana, Dhanusha Gihan. (2024a). “Lifting import ban on automobiles: Sri Lanka sleepwalks into disaster.” Daily FT (12 November): https://www.ft.lk/columns/Lifting-import-ban-on-automobiles-Sri-Lanka-sleepwalks-into-disaster/4-769115

Pathirana, Dhanusha Gihan. (2024b). “Sri Lanka’s ISB restructure: Debt trap backed by IMF and Ceylon Chamber of Commerce.” Daily FT (31 October 2024): https://www.ft.lk/columns/Sri-Lanka-s-ISB-restructure-Debt-trap-backed-by-IMF-and-Ceylon-Chamber-of-Commerce/4-768633

Pathirana, Dhanusha Gihan. (2024c). “House of Cards: Sri Lanka’s Sovereign Bond fiasco and precarious balancing act of Central Bank.” Daily FT (11 December): https://www.ft.lk/columns/House-of-Cards-Sri-Lanka-s-sovereign-bond-fiasco-and-precarious-balancing-act-of-Central-Bank/4-770342

PublicFinance.lk. 2023. “Defence Sector Claims Nearly Half of State Salaries.” (2 June). Available at https://publicfinance.lk/en/topics/defence-sector-claims-nearly-half-of-state-salaries-1685706186

Ranasinghe, Imesh. (2025). “Rs. 965 b forgone in taxes over 21 months.” The Morning (21 February): https://www.themorning.lk/articles/1vAcIV5cJIoSzg2yFnsv

Rizkiya, Nuzla. (2025). “Rs.135 bn defence allocation raises transparency concerns: top economist.” Daily Mirror (19 February): https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/Rs-135-bn-defence-allocation-raises-transparency-concerns-top-economist/108-302679

Ruwanpura, Kanchana. (2025). “Karl Polanyi in Sri Lanka: Odious Debt and Corrupted Capitalism.” Journal of Economic Issues, 59 (1): 1-16. Open access at https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2025.2455293

Samaraweera, Buddhika. (2024). “$ 4 billion annual loss due to export/import mis-invoicing.” The Morning (15 May): https://www.themorning.lk/articles/pnCkoJ05P0JP2dso8yzx

Toussaint, Eric. (2025). “The policies of Sri Lanka’s new government: a historic opportunity lost.” Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM) (14 February). Available at https://www.cadtm.org/The-policies-of-Sri-Lanka-s-new-government-a-historic-opportunity-lost

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (2023). 2024 Regional Human Development Report Making Our Future: New Directions for Human Development in the Asia-Pacific. Bangkok: United Nations Development Program. Available at https://www.undp.org/asia-pacific/publications/making-our-future-new-directions-human-development-asia-and-pacific

Wedagedera, Amali. (2025). “Adjusting and adapting inside IMF prison.” Daily FT (22 January): https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Budget-2025-Adjusting-and-adapting-inside-IMF-prison/14-772076

World Bank. (2024). “Sri Lanka Development Update 2024.” World Bank Group (10 October). Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/srilanka/publication/sri-lanka-development-update-2024

Yukthi, Institute of Political Economy, and Debt Justice. (2024). “Sri Lanka’s unfair debt restructurings with bondholders.” Debt Justice (26 July). Available at https://debtjustice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Sri-Lanka-debt-restructurings_07.24.pdf

You May Also Like…

‘Guru-Ship’: An Epistemological Turn in My Anthropological Education

Sanmugeswaran Pathmanesan

This paper narrates the epistemological shift that took place in my anthropology learning journey, mapping how the...

Gananath: Renaissance Man

R. L. Stirrat

I met Gananath in July 1969 on the day I first arrived in Sri Lanka, Edmund Leach and Stanley Tambiah having imposed...

A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka. Darshi Thoradeniya. Orient BlackSwan (New Delhi), 2024.

Carmen Wickramagamage

Darshi Thoradeniya’s book, A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka, unearths the submerged and...