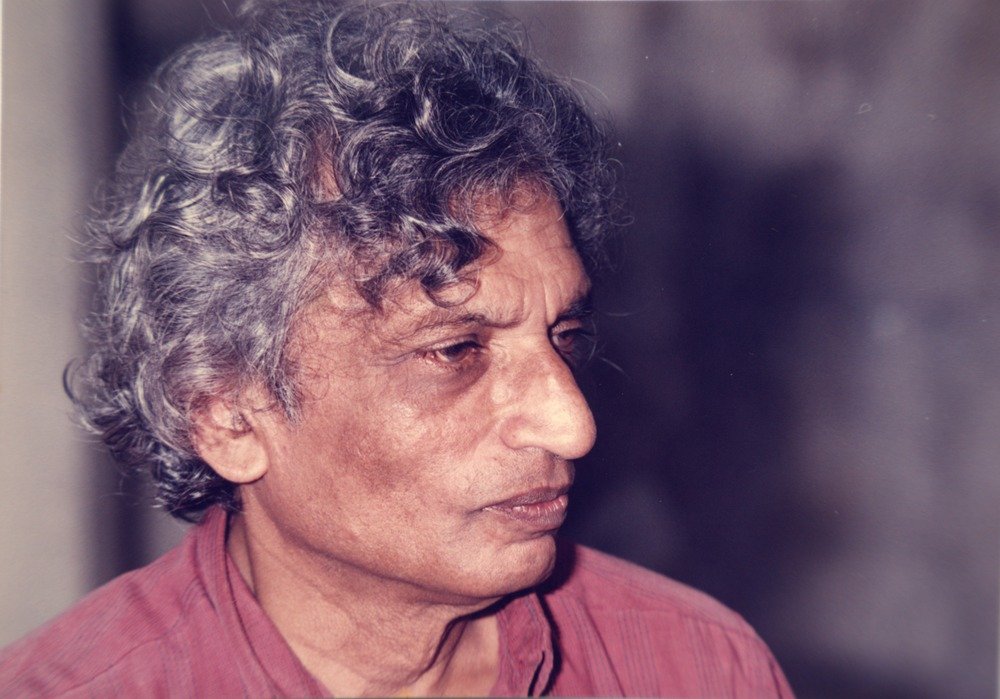

Gananath: Renaissance Man

R. L. Stirrat

I met Gananath in July 1969 on the day I first arrived in Sri Lanka, Edmund Leach and Stanley Tambiah having imposed their naive research student on the Obeyesekeres. Throughout my first period of field research, between 1969 and 1971, Gananath and Ranjini’s house in Kandy provided a refuge from fieldwork.

What developed was not so much an anthropological relationship, but more importantly, and for me more significantly, one of personal friendship, a friendship which endured for the next half century. I can’t remember much in the way of anthropological discussions from those early years; although I do remember Gananath holding forth on many topics, providing much of my education on Sri Lanka.

Having been brought up in the disciplinary structure of British higher education, one of the first things that struck me in the early days of knowing Gananath was his rejection of disciplinary boundaries. This was most evident in his love of poetry, drama and literature, and the way that his anthropology had its roots in literature rather than an interest in the social sciences per se.

Ranjini tells a story, that as a boy Gananath patronised the ‘walking libraries’, where book sellers carried tall piles of books on their heads and walked from house to house—just like the Chinese cloth merchants and the walking jewellery antique dealers, whom the women of the households used to patronise. She said he bought a book for ten cents, read it, and returned it, to exchange for another the following week. The result was his broad intellectual knowledge and experience.

At university, his love of English poetry, especially Chaucer, Shakespeare, even Pope, and later Yeats and Hardy, developed partly under the influence of Lyn Ludowyk, grew alongside a sense of a lost heritage and a need to recover his cultural roots. This led to him at weekends jumping on a train, getting off when he felt like it, chatting with villagers and listening to their stories or kavi or whatever they were talking about. By the time I knew Gananath, he was as likely to recite a kavi, as he was to declaim one of Hardy’s poems.

All this is alluded to in the preface to The Cult of the Goddess Pattini where Gananath describes how this background in literature influenced or rather determined his style of anthropology: “I knew nothing of contemporary anthropology … I had my anthropological education from such unlikely people as T.S. Eliot and W.B. Yeats and via them Frazer, Harrison and the British anthropological classicists”.

Thus his first field research focused not on a particular place but on a cult practised over a large geographical area. Even though his “anthropological education” might be grounded in the work of British literati, it was also grounded in what he described as an ultimately futile “romantic quest for the really real” in Sri Lankan culture; and a wider reflection on the nature of culture and identity. This preoccupation with ‘roots’ is even apparent in his seemingly most ‘orthodox’ volume, Land Tenure in Village Ceylon, which he later describes in the preface to The Work of Culture as a “study of the kind of village society into which I was born and which I left … to study in private schools in Colombo”.

Looking over his work as a whole, one of the themes which stands out is this refusal to be restricted by disciplinary boundaries.

Thus there is the series of works in what could be seen as the interface between anthropology and psychoanalysis such as Medusa’s Hair and The Work of Culture.

Another series focuses on anthropology and religious studies—The Cult of the Goddess Pattini, Imagining Karma, Karma and Rebirth and The Awakened Ones.

Then there are the volumes which are concerned, more or less, with history and western representations of the non-western world, Cannibal Talk and The Apotheosis of Captain Cook, as well as his later volumes on the Veddahs, on the Kandyan kingdom and more generally on Sri Lankan pasts.

But to characterise Gananath’s work in this way, to look for academic categories and interfaces, is I think to misrepresent what is so interesting about his work and characterised him as a person: not just his rejection of disciplinary boundaries, but a rejection of their significance and a questioning of their reality.

The result was his ability to move, seemingly effortlessly, across a whole range of intellectual areas. So conversations with him were never boring. However, at times I must admit that I often became lost at the speed with which he could move from one topic, or what I would see as one discipline, to another; or with the assumptions he made about my knowledge of history, philosophy, or psychology.

In his academic work it was not simply a matter of ignoring or bridging the gaps between disciplines but seeing these gaps as irrelevant; as impediments to thought and understanding. In many ways he fulfilled the model of a ‘renaissance man’, focused not on narrow disciplinary issues but on more general, more important, questions.

Yet whilst Gananath in many ways epitomised the cosmopolitan intellectual, at home in the world of global academia, there was always a sense in which this related to the more local world of Sri Lanka.

Even in his book on Captain Cook and Hawaii, about as far away as one can get geographically from Sri Lanka, he stresses that he is writing about ‘terror’, and that what he has to say about Cook and Hawaii in the eighteenth century is equally relevant to Sri Lanka in the strife-torn 1990s.

And, moving in a different direction, his later work on the history of the Kandyan kingdom, argues that local, almost parochial, interests can, intellectually at least, have global significance.

This process of continually linking the cosmopolitan with the more local in his academic work was also characteristic of Gananath as a person. On one hand, when we visited him he always seemed at home wherever he was, whether it be Princeton, Paris, the Netherlands, Delhi, or London. He was in a sense a global person, part of a cosmopolitan intellectual elite.

Yet at the same time, Gananath was no rootless cosmopolitan and was always grounded in his sense of being a Sri Lankan. He was always very much concerned with the political issues of the time. But there was no room in his thinking for narrow minded nationalism: his values were global.

Gananath was not always easy: he could be opinionated and was at times difficult. He did not suffer fools gladly—although he did make an effort to put up with them. He obviously enjoyed adulation and had a certain charisma; yet at the same time he recognised their dangers and could easily withdraw into himself. He was generous in his opinions of others, recognising not only their intellectual virtues but also their personal qualities.

The Gananath I remember, is not just the great anthropologist he undoubtedly was, but also a generous and supportive friend to myself and my family. I remember him playing on the floor with my infant son when we visited him and Ranjini in the Netherlands; sitting under an apple tree in our garden reading trashy detective novels; or arranging for a room in the Queen’s Hotel so that my small daughter could see the Perahera.

In The Work of Culture, Gananath quotes approvingly a comment from Edmund Leach—another anthropological maverick whose intellectual background was outside anthropology—that “an ethnographic monograph has much more in common with an historical novel than with any kind of scientific treatise”; and that anthropologists write about themselves when they write their monographs. “Any other sort of description turns the characters of ethnographic monographs into clockwork dummies”.

How far Leach actually meant what he wrote—he was always prone to exaggeration and innuendo—and how far Gananath fully subscribed to this view of ethnography is unclear. Despite their very different approaches to anthropology they were friends; and Leach was partly responsible for Gananath being the first holder of the Esperanza Fellowship in Cambridge, the first of many honours.

But even so, through their ethnographies, through the sorts of questions they were posing, and through the way they presented their analyses, we can get a glimpse of the complex minds of both men, both writing about themselves.

This takes me back to Hardy and his influence on Gananath’s anthropology. In the preface to one of his last books, Stories and Histories, Gananath mentions that, as Hardy put it, “we are all time-torn beings”; that history is always in the making and that in the process we lose the past. Part of that past involves “the worst”, but it is only through looking at the worst, says Hardy, that we can determine a better way to the future—what Hardy called “evolutionary meliorism”.

This belief in the ultimate humanity of people, and that through action a better future for all can be gained, is what characterises Gananath not just as an anthropologist but as a man.

Roderick L. (‘Jock’) Stirrat is Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of Sussex, Brighton; and author most recently of Embracing Change in Coastal Sri Lanka: Local Strategies in a Global Context (Berghahn Books, Oxford 2025).

Photo credit: Kumari Jayawardena/ Social Scientists’ Association

You May Also Like…

A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka. Darshi Thoradeniya. Orient BlackSwan (New Delhi), 2024.

Carmen Wickramagamage

Darshi Thoradeniya’s book, A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka, unearths the submerged and...

From Living With, to Drowning Under, Floods: A Village Transformed

Shashik Silva

Welewatta has always flooded. This village in the Kolonnawa Divisional Secretariat (DS), home to 1424 families, floods...

Iran: Solidarity with popular struggles against poverty, unemployment, discrimination, and repression

Editors and Vahed

Once again, the Iranian people are on the streets against their repressive rulers. Once again, the Islamic Republic...