‘Dead Catting’: Manufacturing Moral Panic in Sri Lanka

Ruben Thurairajah

In Colombo Fort, tourists stroll past decaying colonial buildings, unaware that the air is thick with invented fear. A hotel concierge smiles politely, but in the newspapers, the same streets are said to be under siege: by immorality, by difference, by foreign desires.

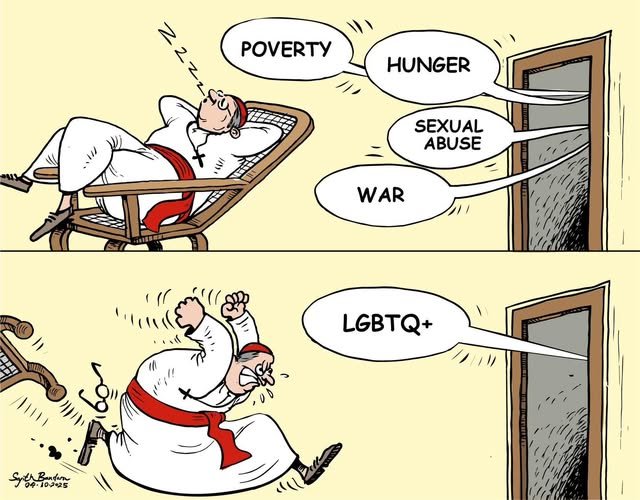

Men travelling together, a rainbow flag fluttering above a cafe, a dedicated sexual health and wellbeing clinic, a proposed brochure for LGBTQ friendly tourism: these are cast as existential threats to age-old culture. Across the country, Buddhist monks and Catholic priests shriek in unison, failed politicians’ issue dire warnings, and a moral panic sweeps society, discarding reason and kindness in its wake.

The island, advertised world over as tropical paradise, where strangers are greeted with warm smiles, where the Buddhist tradition of mindfulness originated, now measures welcome in suspicion.

Predictable Storms

Sri Lanka has a rhythm to its politics, as predictable as the ferocity of the monsoon. When the rains arrive, they carve the same gullies. When political storms arrive, they wear down the same communities, expose the same fissures. Tamils have been accused of treachery, Muslims of multiplying, and now with weary inevitability; it is the turn of those foreign tourists who may or may not identify as LGBTQ.

Anatomy of a Moral Panic

Moral panic may sound academic, a sociological term. In practice, it is simpler: a manufactured outcry that society is under threat, that tradition is collapsing, that foreign ideas are ready to corrupt the young.

A few columns, a press conference, pronouncements by the cassock-clad and saffron-clothed; suddenly, the streets are alive with suspicion and anxiety. The danger is not the minority, the stranger, or the traveller, but the panic itself, and the license it grants to the usual suspects.

Script Never Changes

Every panic follows a script. It begins with a faint signal: a policy proposal, a circular, a court decision; amplified by voices skilled in outrage. A media house notorious for its daily errors and clickbait headlines, a politician who lost power in the last election eager for relevance, a religious organisation in need of rallying the faithful.

Then comes the chorus: warnings that traditional values are at risk, that children are threatened, that the majority must act before it is too late. Institutions that ought to counter ignorance and prejudice compound them through acts and omissions. Ministers issue “clarifications” that sharpen suspicion.

By the end, a minor policy proposal or even a rumour becomes a theatre of existential struggle, leaving the scapegoated group exposed and defenceless.

Dr Shafi’s Case

Consider the case in 2019 of Dr. Shafi, the Muslim gynaecologist accused of sterilising Buddhist women. No evidence was produced, but politicians turned him into a cipher of conspiracy, a demographic bogeyman. His career was ruined, his family ostracised and driven out, his name permanently stained. The accusation mattered less than its utility. Once suspicion was seeded in people’s minds, it bloomed into political advantage in the campaign for the presidency that year.

The genius of a moral panic is that it changes costume while keeping the plot identical.

The New Target: LGBTQ Tourism

Now the same politicians have returned to the same stage, this time with LGBTQ tourism as the target. They warn in familiar, alarmist tones, that promoting Sri Lanka as a destination for LGBTQ travellers will carry the HIV virus and spread it across the island.

Such statements, broadcast and amplified, are presented as urgent warnings to the nation. Scientific evidence and public health data are irrelevant. The moral panic is complete: foreign tourists are now cast as vectors, as contamination, as threat.

The same politicians who once stoked fear of Dr. Shafi’s supposed sterilisation plots now mobilise dread of gay tourists. The trope is identical; only the garb has changed.

Hospitality Turned Hostility

The trigger is the same Sri Lankan political theatrics, again. The Tourism Ministry’s clarification that no campaign would be launched was treated as proof of secret subversion. Hospitality, once the island’s proudest boast, is declared conditional: welcome only if visitors conform to an image of virtue recycled by immoral politicians and hypocritical men in robes whose institutions, for centuries, have preyed on young boys.

In an ice-cold irony, Catholic clergy and Buddhist monks, often competitors for influence, joined hands to denounce a common enemy. On the surface, it is moral vigilance; underneath, it is a coalition of convenience, bound by a pitchfork of fear rather than principle.

Fear as Political Weapon

Beneath the surface, this panic serves a clearer political purpose: it is a smear campaign against the National People’s Power (NPP) government.

By framing initiatives for LGBTQ inclusion and minority equality as threats to tradition and health, the usual suspects portray the NPP administration as “anti-Sri Lankan”, hostile to the majority, and unfaithful to Asian civilisational values.

In doing so, they attempt to discredit not just one proposal, but the broader quest of the government to advance equality. The moral panic becomes a weapon, diverting attention from policy achievements and reducing progressive governance to suspicion and outrage.

Vocabulary of Virtue

The same words recur: heritage, values, civilisation. Their meaning is vague. Whose heritage? Whose values? The Buddhist monk invokes 2,500 years of civilisation; the Catholic priest invokes universal morality. Both ignore the island’s long history of accommodation: absorbing Indian, Arab, Portuguese, African, Malay, Dutch, and British cultures; blending rituals and festivals; learning new languages and fusing cuisines.

The panic insists, however, that purity must be restored.

Why the Pattern Endures

Manufactured panic is useful. It shows the government as weak. It distracts Sri Lankans from the economic bankruptcy and political calamities of the failed political class. It transfuses new political energy into zombie parties. Panic gives preachers a cause when congregations wander away to explore science and reason. Accusing a minority of undermining civilisation costs nothing; it demands no solution for unemployment or inequity. It is manipulation of the many by scaremongering. This is exactly what political manipulators like Boris Johnson, disgraced ex-prime minister of the (dis-)United Kingdom, calls the ‘dead cat’ strategy: the diversion of attention away from real everyday issues, by creating shock and fear around counterfeit intrigues.

Cost of Fear

The consequences are tangible. Communities are scarred. Trust is eroded. Professionals like Dr. Shafi lose livelihoods. Tourists hesitate to come. Young people who discover they are different retreat into silence. The cost is borne by those who can least afford it, while the architects of panic sharpen their knives for the next scapegoat.

Breaking the Pattern

The storm follows a familiar course. A rumour inflamed into existential threat, alliances forged across religious divides, institutions paralysed by fear or calculation, the majority reassured that it is under siege and justified in prejudice.

The pattern is rehearsed; it barely surprises.

The remedy is unromantic. Institutions must act without fear, courts should enforce constitutional promises, politicians should risk defeat. Citizens must develop civic literacy, recognise the pattern, and refuse to be mobilised by fear.

Yet the habit of blaming others is part of the old Sri Lankan political theatre. It is a performative practice, reinforced by decades of political manipulation. It is political skulduggery by the old actors, to cry cultural contamination, rather than aid in reforming the economy or the public transport or education system.

Rehearsal Continues

The danger of moral panic lies not only in harm to minorities, but in its political benefit of those who manufacture it. Each panic rehearses the next and promises political power and control. Until citizens of Sri Lanka denounce this script, failed politicians will continue to invent enemies and recycle old fears. And voters will mistake bigotry for governance.

The current spectacle is familiar and pitiful. The manufacture of fear to cover political weakness, smear a government supporting equality, and maintain the rhythm of invented enemies.

Until the country treats equality as practice rather than political posture, it will continue to damage its citizens, its guests, its economy, and itself.

Ruben Thurairajah is a Yorkshire-based doctor in Britain’s National Health Service; who also tweets https://x.com/RubenThurairaj and writes https://drruben.substack.com/

You May Also Like…

Gananath: Renaissance Man

R. L. Stirrat

I met Gananath in July 1969 on the day I first arrived in Sri Lanka, Edmund Leach and Stanley Tambiah having imposed...

A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka. Darshi Thoradeniya. Orient BlackSwan (New Delhi), 2024.

Carmen Wickramagamage

Darshi Thoradeniya’s book, A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka, unearths the submerged and...

From Living With, to Drowning Under, Floods: A Village Transformed

Shashik Silva

Welewatta has always flooded. This village in the Kolonnawa Divisional Secretariat (DS), home to 1424 families, floods...