The Hidden Politics of Critical Agrarian Studies: A Reply to Urs Geiser

Tom Brass

In a recent contribution to Polity, Urs Geiser (2023) endorsed Critical Agrarian Studies (CAS), as an approach he wishes to apply to the study of rural society in Sri Lanka. To this end, he draws a contrast between, on the one hand, earlier Marxist debates about the peasantry, those of the 1970s and 1980s, and, on the other, “new challenges to the field of agrarian studies” said to be provided by CAS. The latter is positioned by Geiser as the ‘other’ of – and, indeed, the only feasible alternative to – market-based development theory lacking “a critical perspective that would address power relations [and] normatively… embedded in the modernisation project” (2023: 43-44). This, he suggests, CAS would do in three ways: first, by reinterpreting theory about class; second, by refocusing methodology away from household heads and onto its kinship components; and third, by seeking out politically radical/progressive policies.

In what follows, the efficacy of this approach is questioned. Despite accepting that “[c]ontemporary agrarian studies need critical introspection to clarify their own ideological position” (Geiser 2023: 46), this is not considered further in terms of what it might reveal. Although the issue is presented by Geiser merely as an assessment of what insights might be obtained from the application of CAS, it is clear that he is broadly sympathetic to this approach, regarding it as progressive, and thus also as having much to offer both analytically and politically.[1] It is, in short, an option that “invites attention” (Geiser 2023: 47).

Populism, or the identity that dares not speak its name

As clear is that, while the apparent faults of Marxist theory are set out in some detail (Geiser 2023: 40-43), far less evident is the kind of alternative on offer from CAS. It is almost as if suddenly, the latter had sprung from nowhere, untainted by any political agenda, and was thus just a matter of common sense only remaining to be recognised as such by everyone. For this reason it is important to enquire what precise ideas and meanings lie behind its description by Geiser in vague, apolitical and unhistorical terms like “more nuanced theoretical approaches”, “this broader field of nuanced studies”, and “these [older] debates need to be critically reflected upon, and made more nuanced” (2023: 40, 44).[2] The sole clue as to what CAS advocates merely repeats the equally vague and unhelpful description found in Akram-Lodhi et al. (2021).[3]

It is argued here that under these various disguises (“nuanced” alternatives), however, lies a very different story, a political one that Geiser does not tell. Consequently, it is impossible to understand his arguments without the additional knowledge of three things: the political background, consisting of a debate between Marxists and populists; its historical longevity, going back well beyond the 1970s; and what lies behind the current rise to academic prominence of populism, together with its implications for development theory.[4] Missing from the account by Geiser, therefore, is that far from being untainted by a political agenda, CAS is an exemplar of what is termed the ‘new’ populist postmodernism, the object of which is to establish and consolidate an agrarian populist hegemony over the way peasant economy and society is interpreted.[5] The negative outcomes of this, it is claimed here, have serious political implications for the study of development and the role in this of peasants.

Comprising a number of currently fashionable paradigms in the social sciences – among them not just CAS but also subaltern studies, everyday-forms-of-resistance, empire, multitudes, and global labour history – a longstanding agrarian populism fuses with recent postmodern theory to form a mutually supportive discourse, that of the ‘new’ populist postmodernism.[6] The latter combines the agrarian populist espousal of ‘natural’/harmonious rural-based/small-scale economic activity (peasant family farming, handicrafts) and culture (religious, ethnic, national, regional, village, family identities derived from Nature) with the championing by postmodern theory of what it categorises as innate and ‘authentic’ cultural identities (nationality, ethnicity) encountered at the rural grassroots (traditional community, indigenous culture and organisation), all of which are deemed empowering, historically eternal, and thus non-transcendent.[7]

Equally significant is the antipathy towards Marxist political economy shared by populism and postmodern theory. The development approach of Marxist theory is dismissed as no longer relevant to an understanding of rural society for a series of interconnected reasons. First, its objection to the continued efficacy of the peasant economy, and its form of smallholding private property.[8] Second, its opposition to mobilisation based on non-class ‘otherness’. Third, for imposing an inappropriate Eurocentric development model on non-metropolitan (= Third World) contexts. And fourth, for supporting urban-based large-scale economic activity (industrialisation, manufacturing, collectivisation, planning, massification) and its accompanying institutional/relational/systemic effects (class formation/struggle, revolution, socialism, bureaucracy, the state).

Perils of misunderstanding populism

A sign of the difficulties faced by Geiser in his “search for progressive policies [based on] normative thoughts” derived from CAS is a double misrecognition as a result of not addressing its political identity. On the one hand endorsing as a way forward the agrarian populist views of Henry Bernstein; and on the other missing the fact that the importance of internally differentiating peasant households had already been undertaken by Marxism in the pre-CAS era. Citing the work of Bernstein as an indication of the theoretical path to be followed, therefore, Geiser (2023: 40-41, 44) omits to ask what kind of politics informs this approach. Overlooked thereby is that Bernstein is himself an exponent of agrarian populism, as has been demonstrated by others on numerous previous occasions.[9]

Recommending also that CAS query a “methodological focus on the head of the household [which] does not suffice”, Geiser suggests that it adopt “[i]nstead an understanding of family or household internal dynamics [because these are] crucial” (2023: 45). This, he continues, is because such a methodology “raises questions on how we understand and generalise, rural life”. What is missed is that precisely such a methodology has been in place for many decades now, and is practiced by the very approach that has itself been deemed wanting: hence this same emphasis on how kinship and quasi-kinship relations in the peasant family are themselves transected by class, and thus have of necessity to be seen not simply as united on ties of affectivity but rather as divided in terms of property (land, means of production, labour-power), is found in research undertaken by a Marxist anthropologist.[10] In short, that the peasant family is composed of those who do not always possess the same economic position and interests has long been known about.

More broadly, the negative political consequences of replacing Marxism with the ‘new’ populist postmodernism as a development model are not difficult to discern. Unlike Marxism, for which struggle between capital and labour generates the necessary consciousness of class that prefigures and makes possible a transition to socialism, the agency pursued by ‘new’ populist postmodernism consists only of everyday forms of (peasant) resistance designed to achieve nothing more than a return either to a pre-capitalist systemic order or a more benign version of capitalism. Both these steady-state objectives are chimeras, since the accumulation trajectory, once established, necessarily becomes global and leads inevitably to neoliberalism. What capital wants from the peasantry in these circumstances is its labour-power, which – when reconstituted as part of a burgeoning global industrial reserve army on which producers everywhere can draw – serves to police and force down the wages/conditions gained over years of struggle and organisation by the existing workforce in metropolitan nations, adding thereby to the intensity of labour market competition in such contexts, which in turn fuels the populist backlash in these places.

By deprivileging struggle based on class and instead privileging non-class identity, therefore, the ‘new’ populist postmodernism merely throws petrol onto these flames, playing directly into the hands of conservatism and the far right. It makes difficult, if not impossible, the formation and reproduction of a solidarity based not on ethnic or national identity but on class. Moreover, where the industrial reserve takes the form of immigration, it permits populists in the receiving country to advocate unity between capital and labour of the same nationality, fracturing the possibility of a common mobilisation involving migrant and local aimed at transcending the kind of economic advantage producers enjoy from continuing access to the industrial reserve. To the postmodern argument emphasising the cultural identity of the migrant-as-‘other’-nationality, populists counterpose an argument similarly emphasising cultural identity, only this time the nationality of the non-migrant worker. Each component of the workforce is encouraged to see any ensuing conflict not as an issue about the economic sameness of class but rather as one based on national cultural difference.

What Marxism does…

Turning, finally, to an inaccurate, not to say a mildly derogatory, reference by Geiser to my role as editor of The Journal of Peasant Studies (JPS). I am accused by him of adhering to a “strict Marxist political economy, disqualifying all other research on the peasantry as ‘a-historical, cultural essentialism of postmodern theory’” (Geiser 2023: 40), which conveys the impression that I refused either to engage with this approach or to publish anything informed by it, both of which are false. That the accusation is quite simply untrue would be clear from the part of that quote not mentioned by Geiser, which pointed out that postmodernism “has been permitted to colonise non-economic discourse, more or less unchallenged. The effect on the study of development and the role in this of peasants and workers has been deleterious, leading in some instances to the denial of the desirability/possibility of economic development itself”, concluding that “peasantries will be studied [by JPS] within the wider systems and historical situations in which they exist” (JPS 2000: 1, 2).

As misplaced is the dual inference that, as a Marxist, I did not engage with postmodern theory and that consequently, as editor, I published nothing containing such views. To take but one example, after having criticised postmodern theory about Latin American peasants (Brass 2003) in a special issue of JPS edited by me, I invited an influential advocate of such an approach to compose a reply, which was published soon after (Beverley 2004). To this I myself responded a while later (Brass 2006), pointing out in what was an amicable conclusion that

we on the political left have to be aware of both the epistemological lineage and theoretical direction of any discourse which we endorse, and in particular the vexatious issue of ideological proximity. (Both here and above the term ‘we’ is used deliberately and in comradely fashion, expressing the view that Beverley is not perceived as being irretrievably lost to the socialist cause). (2006: 322)[11]

So much for the view that when I edited the JPS it adopted an exclusionary policy towards postmodern theory on account of my having “[disqualified] all other [non-Marxist] research on the peasantry” (Geiser 2023: 40).

Tom Brass formerly lectured in the Social and Political Sciences Faculty at Cambridge University, and directed studies in SPS for Queens’ College. He carried out fieldwork research in Latin America and India during the 1970s and 1980s, and is the second-longest serving editor of The Journal of Peasant Studies (1990-2008). His books include New Farmers’ Movements in India (1995), Free and Unfree Labour: The Debate Continues (1997), Towards a Comparative Political Economy of Unfree Labour (1999), Peasants, Populism and Postmodernism (2000), Latin American Peasants (2003), Labour Regime Change in the Twenty-First Century (2011), Class, Culture and the Agrarian Myth (2014), Labour Markets, Identities, Controversies (2017), Revolution and Its Alternatives (2019), Marxism Missing, Missing Marxism (2021), Transitions (2022), Interrogating the Future (2024), and Critiques: In Defence of Development (2025).

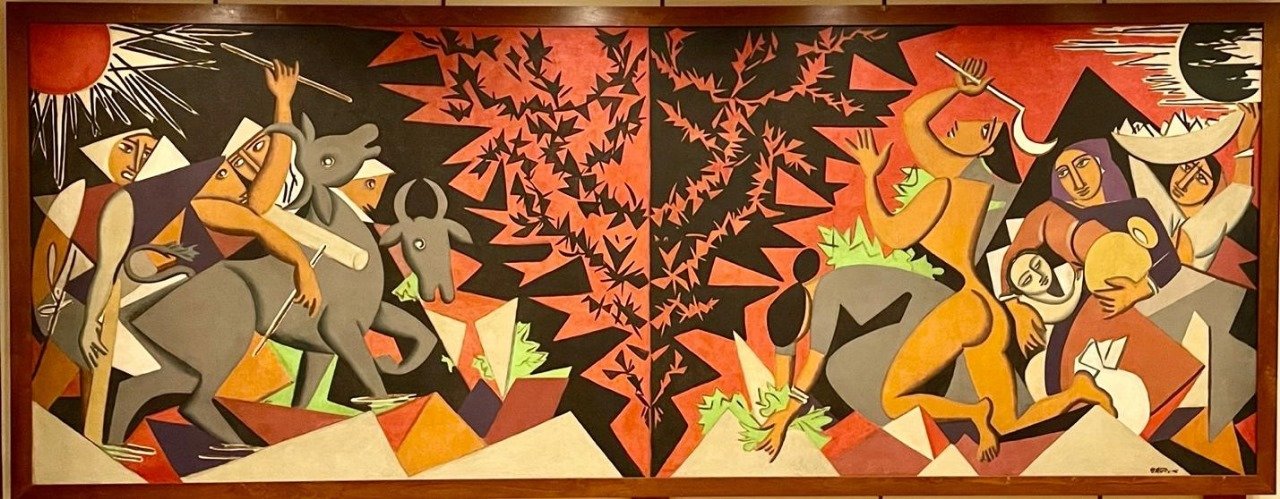

Image credit: George Keyt (1976) oil on canvas, photographed by Angeline Ondaatjie

References

Akram-Lodhi, Haroon A., Kristina Dietz, Bettina Engels, and Ben M. McKay (Eds.). (2021). Handbook of Critical Agrarian Studies. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Assies, Willem. (2005). “The Challenge of Diversity in Rural Latin America: A Rejoinder to Jean-Pierre Reed (and Others)”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 32(2): 361-371.

Brass, Tom. (1980). “Class Formation and Class Struggle in La Convención, Peru”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 7(4): 427-457.

Brass, Tom. (1983). “Agrarian Reform and the Struggle for Labour-Power: A Peruvian Case-Study”. The Journal of Development Studies, 19 (3): 368-389.

Brass, Tom. (1986). “The Elementary Strictures of Kinship”, Social Analysis, 20: 56-68.

Brass, Tom. (2003). “On Which Side of What Barricade? Subaltern Resistance in Latin America and Elsewhere”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 29(3-4): 336-399.

Brass, Tom. (2006). “Subaltern Resistance and the (‘Bad’) Politics of Culture: A Response to John Beverley”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 33(2): 304-344.

Brass, Tom (2022a). “Neo-populist Fables: The Other World of A.V. Chayanov”. Critical Sociology, 48(7-8): 1325-1343.

Brass, Tom. (2022b). “Marxism, Peasants, and the Cultural Turn: The Myth of a ‘Nice’ Populism”. In David Fasenfest (Ed.), Marx Matters (269-299), Leiden: Brill.

Brass, Tom. (2023). “Critical Agrarian Studies as Populist Land-Grab”. Critical Sociology, 49(3): 563-573.

Beverley, John. (2004). “Subaltern Resistance in Latin America: A Reply to Tom Brass”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 31(2): 261-275.

Chayanov, A.V. (1966 [1923]). The Theory of Peasant Economy (edited by Daniel Thorner, Basile Kerblay, and R. E. F. Smith), Homewood, Illinois: Published for the American Economic Association by Richard D. Irwin, Inc.

Desmarais, Annette-Aurélie. (2002). “The Vía Campesina: Consolidating an International Peasant and Farm Movement”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 29(2): 91-124.

Geiser, Urs. (2023). “Reflections on Critical Agrarian Studies in Sri Lanka”. Polity, 11(2): 40-48.

Gibbon, Peter, and Michael Neocosmos. (1985). “Some Problems in the Political Economy of ‘African Socialism’”. In Henry Bernstein and Bonnie K. Campbell (Eds.). Contradictions of Accumulation in Africa: Studies in Economy and State (153-206). London and Beverley Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

The Journal of Peasant Studies. (2000). “Editorial Statement”, 28(1): 1-2.

Nugent, Stephen. (2003). “Whither O Campesinato? Historical Peasantries of Brazilian Amazonia”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 29(3-4): 162-189.

Sivakumar, S.S. (2001). “The Unfinished Narodnik Agenda: Chayanov, Marxism and Marginalism Revisited”. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 29(1): 31-60.

Note

[1] Hence the view that “a contemporary re-engaging with agrarian studies…requires a critical reflection on such concepts and notions that informed the [earlier, Marxist] debates” (Geiser 2023: 43).

[2] Other, similarly general terms that reveal little about the politics involved, but are nevertheless deployed by Geiser in distancing himself from Marxism include “diverse theoretical approaches within [the] social sciences”, “alternative approaches to understand agrarian structure and change”, “a broader range of theoretical approaches [corresponding to] what I call critical social science approaches”, and “a broad interdisciplinary framework, inspired by theory” (2023: 40, 42, 44).

[3] “Critical agrarian studies represents a field of research that unites critical scholars from various disciplines concerned with understanding agrarian life, livelihoods, formations and their processes of change. It is ‘critical’ in the sense that it seeks to challenge dominant frameworks and ideas in order to reveal and challenge power structures and thus open up the possibilities for change.” (Akram-Lodhi et al. (2021) cited in Geiser 2023: 44)

[4] Significantly, populist discourse emerged historically from opposition by conservative politics to the Enlightenment, and the consequent need to gain popular support among the masses for nationalist ideology. It flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century when peasant movements throughout Europe mobilised against either capitalist development in the countryside or the transition to socialism. Prior to the 1939-45 war, most peasant parties throughout Europe and Asia were strongly nationalist, and agrarian populist organisations generated much rural grassroots support for right wing (as in the United States, India, Bulgaria and France) or fascist movements (as in Japan, Spain, Italy, Germany, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia and Romania). This was because, for populism, a ‘pure’ (or middle) peasantry engaged in smallholding cultivation within the context of an equally ‘pure’ village community (that is, unsullied by an external capitalism or socialism) was presented as embodying all the culturally-specific attributes – timeless/sacred ‘natural’ and ancient bonds such as ethnicity, language, religion, customs, dress, songs, traditions – that were constitutive of a ‘pure’ national identity.

[5] Reticence about the political identity of CAS as an upholder of agrarian populism is a characteristic Geiser shares with Akram-Lodhi et al. (2021). Marxists, by contrast, do not attempt to hide their political allegiance. For an extended critique of CAS, see Brass (2023).

[6] Since details about the ‘new’ populist postmodernism, what it stands for, and why, are contained in everything I have written over the past four decades, there is no point referencing just one publication as distinct from any another. The nearest Geiser comes to acknowledging the presence of postmodern influence is the brief observation that in Sri Lanka “most researchers applied more cultural theories to engage with nationalism, identity politics, processes of othering” (2023: 43), without enquiring further into this process.

[7] Historically – and currently – populism has sought neither a modern going beyond capitalism to socialism, nor the capture/control of the State, but rather a process of State ‘avoidance’ combined with a return to a ‘natural’ village-level social order. Restored thereby is smallholding agriculture based on individual peasant proprietorship that capitalism or socialism had threatened to erode or destroy, the object of populist resistance being simply to re-established the ‘eternal’ family farming system as envisaged by Chayanov (1966). In contrast to Marxist theory, populism maintained both that an undifferentiated peasant economy was an innate organisational form, and that it would continue to exist despite ‘external’ systemic transformations (from feudalism to capitalism, and from the latter to socialism). Since in this discourse ‘peasant-ness’ is equated not just with smallholding agriculture but also with culture and national identity, depeasantisation becomes synonymous with deculturalisation and the erosion (or loss) of national identity.

[8] Marxist theory has always insisted that, in the course of capitalist development, the peasantry was differentiated along class lines, its top stratum (= rich peasants) consolidating means of production and becoming small capitalists, while its increasingly landless bottom stratum (= poor peasants) joined the ranks of the proletariat. For this reason, to regard peasants as a uniform category – as did populism – was mistaken, since these distinct rural strata possessed economic and political interests that were not just different but antagonistic. Instead of private property – the individualist smallholding economy – supported/advocated by populists, a Marxist programme of agrarian reform was based on collective agriculture, where rural property was owned/controlled by the state. Among the reasons for this was that the latter approach facilitated central planning.

[9] See, for example, Gibbon and Neocosmos (1985) and Brass (2022b).

[10] On the need to internally differentiate peasant families and kinship in this manner, see Brass (1980: 440ff.; 1983; 1986).

[11] In a similar vein, not only did I publish other endorsements of agrarian populism and postmodernism during my time as JPS editor (e.g., Sivakumar 2001: Desmarais 2002; Nugent 2003; Assies 2005), but for my part I have also continued to engage thereafter with the neopopulist theory of Chayanov (Brass 2022a).

You May Also Like…

Gananath: Renaissance Man

R. L. Stirrat

I met Gananath in July 1969 on the day I first arrived in Sri Lanka, Edmund Leach and Stanley Tambiah having imposed...

A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka. Darshi Thoradeniya. Orient BlackSwan (New Delhi), 2024.

Carmen Wickramagamage

Darshi Thoradeniya’s book, A Critical History of Women’s Health in Modern Sri Lanka, unearths the submerged and...

From Living With, to Drowning Under, Floods: A Village Transformed

Shashik Silva

Welewatta has always flooded. This village in the Kolonnawa Divisional Secretariat (DS), home to 1424 families, floods...